Don’t like the way you write? An artificial intelligence app promises to polish your prose

I am a professional writer, but I often hate my writing. I wish it was more concise and powerful. And it certainly doesn’t read as smoothly as the work of my literary heroes. Recently, I began to wonder: Could a software program make me better at my job?

I am a professional writer, but I often hate my writing. I wish it was more concise and powerful. And it certainly doesn’t read as smoothly as the work of my literary heroes. Recently, I began to wonder: Could a software program make me better at my job?

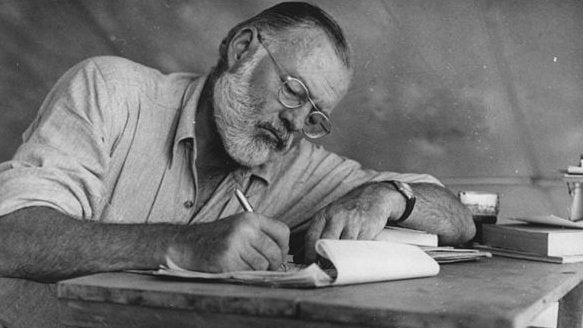

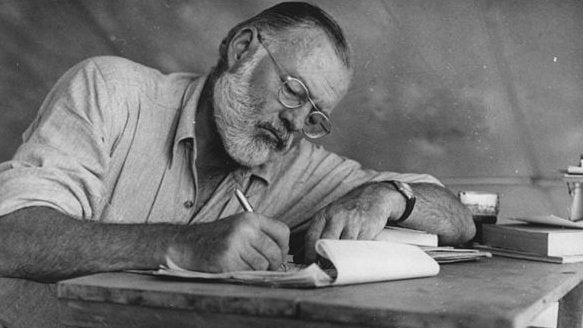

The Hemingway App, an online writing editor created in 2013 by brothers Adam and Ben Long, promises to do just that. “Hemingway makes your writing bold and clear,” the site claims, so that “your reader will focus on your message, not your prose.” If you listen to the app’s advice, it will rid your writing of run-on sentences, needless adverbs, passive voice, and opaque words. There’s no guarantee you’ll crank out the next Farewell to Arms—but the goal is to get you closer to Ernest Hemingway’s clear, minimalist style.

The app uses a crude artificial intelligence that recognizes writing problems through natural language processing. When you copy and paste your text into the Hemingway Editor, it highlights sentences with possible issues in different colors and offers suggested changes. For example, if I write, “This Editor has been used since around 2013,” the words “been used” are highlighted green because I am using the passive voice.

Most of the recommendations offered by the Hemingway App are based on research into readability—that is, how easy it is to understand a given text. Essentially, research shows that long sentences, polysyllabic words, and the passive voice all make it harder for the reader to parse the meaning of a text. (The app wanted me to use “long” instead of “polysyllabic” here, but I resisted.)

Writing for readability often means writing at a lower grade level. But one can write simply while communicating complex ideas. Some of Hemingway’s prose was easy enough for a fifth grader to understand. Yet, for many adults, his writing still remains profound. In eschewing ornamentation, he ensured that each word he wrote was essential.

To see how the app worked, I decided to give it a test. At the beginning of February 2017, I published an article about the effects of protesting based on some brilliant academic research. I was proud of the story, and I hoped that it would be widely read. I thought it was timely and provocative. Unfortunately, the story was not nearly as popular as I hoped.

It seemed like the perfect article to try out on Hemingway. Maybe the app could show me what I could have done to make it easier to read and, thus, more popular. I copy and pasted my article in the Editor.

Yikes! Almost the entire piece was highlighted. The app warned me that my story was written at Grade 13 level (it suggested I bring it down to 9). Twenty-one of my 27 total sentences were “hard” or “very hard” to read. I had also used seven adverbs, more than double the number the app suggests for the number of words in my story.

The main aspect of my writing that the app didn’t like was the length of my sentences. The following sentence, a 43-word monster, received a grade level score of 28. Apparently, you would need to get multiple PhDs to have an easy time reading it:

According to their research, rallies in congressional districts that experienced good weather on Tax Day 2009 had higher turnouts, which led to more conservative voting by the district representative and a substantially higher turnout for the Republican candidate in the 2010 congressional election.

Fair enough. It’s a pretty bad sentence. To placate the app, I broke it up into three sentences. I also got rid of “According to their research,” which was unnecessary. I was writing a story about the academics’ research, of course it was according to them. The new version, below, is at a 10-grade level:

Places that experienced good weather on Tax Day 2009 ended up having very different outcomes. The congressperson voted more conservatively in the good weather districts. There was also higher turnout for the Republican candidate in the 2010 congressional election.

That’s better, right?

In addition to having me break up my sentences, the app alerted me to a few unnecessary uses of adverbs like “primarily” and “substantially.” It also pointed out one use of the passive voice that read better when I made it active. (If you are curious, you can read the original version here, and edited version here.)

I also ignored some of the app’s suggestions. A few were just nonsensical. It suggested I replace the word “demonstrate” with simpler synonyms “prove” or “show,” but I was talking about people going to airports to protest. I rejected other suggestions for stylistic reasons. The app wanted me to remove “really” from the sentence “As it turns out, protest size really does matter.” But I wanted to keep the conversational tone.

In the end, I was able to bring the grade level of my story down from 13 to nine, and shed 34 words along the way. Then I gave the updated version to Kira Bindrim—a Quartz editor who’d edited the original story.

“I think my gut reaction is to prefer the original,” Bindrim wrote to me after reading the Hemingway version. She found the abundance of short sentences choppy, the app’s aversion to colons unreasonable, and worried it was taking away my voice. Her assessment wasn’t all negative, however. “I could see this being a super useful exercise for a writer in the draft stage of a story, to see obvious cuts to flowery/unnecessary language, or to expose potentially confusing sections.”

I can sympathize with her points. I’m actually not a fan of Ernest Hemingway. I find his writing simple to the point of banality. Give me Henry James or Leo Tolstoy instead. I want to be swept away by a compound sentence filled with em dashes and prepositions. The Hemingway App would have ruined the books by my favorite authors.

If you listened to everything that Hemingway App told you, it might ruin your writing, too. But luckily, you don’t have to. You can just take the worthy recommendations and ignore the rest. (In case you were wondering, this story is written at a seventh-grade level. But 18 of the 79 sentences are either hard or very hard to read, and it contains 14 too many adverbs for the app’s liking.)

In the end, I don’t think the Hemingway App can turn you into a great writer. It will not make your work any funnier or more insightful. But it just might make you break up a run-on sentence or remove a useless word. As Hemingway said, “The first draft of anything is shit.” Anything that helps you get past that phase and onto the next is well worth it.