Cape Town

One of Africa’s most celebrated thinkers shared his wisdom with South African students, but they completely missed it.

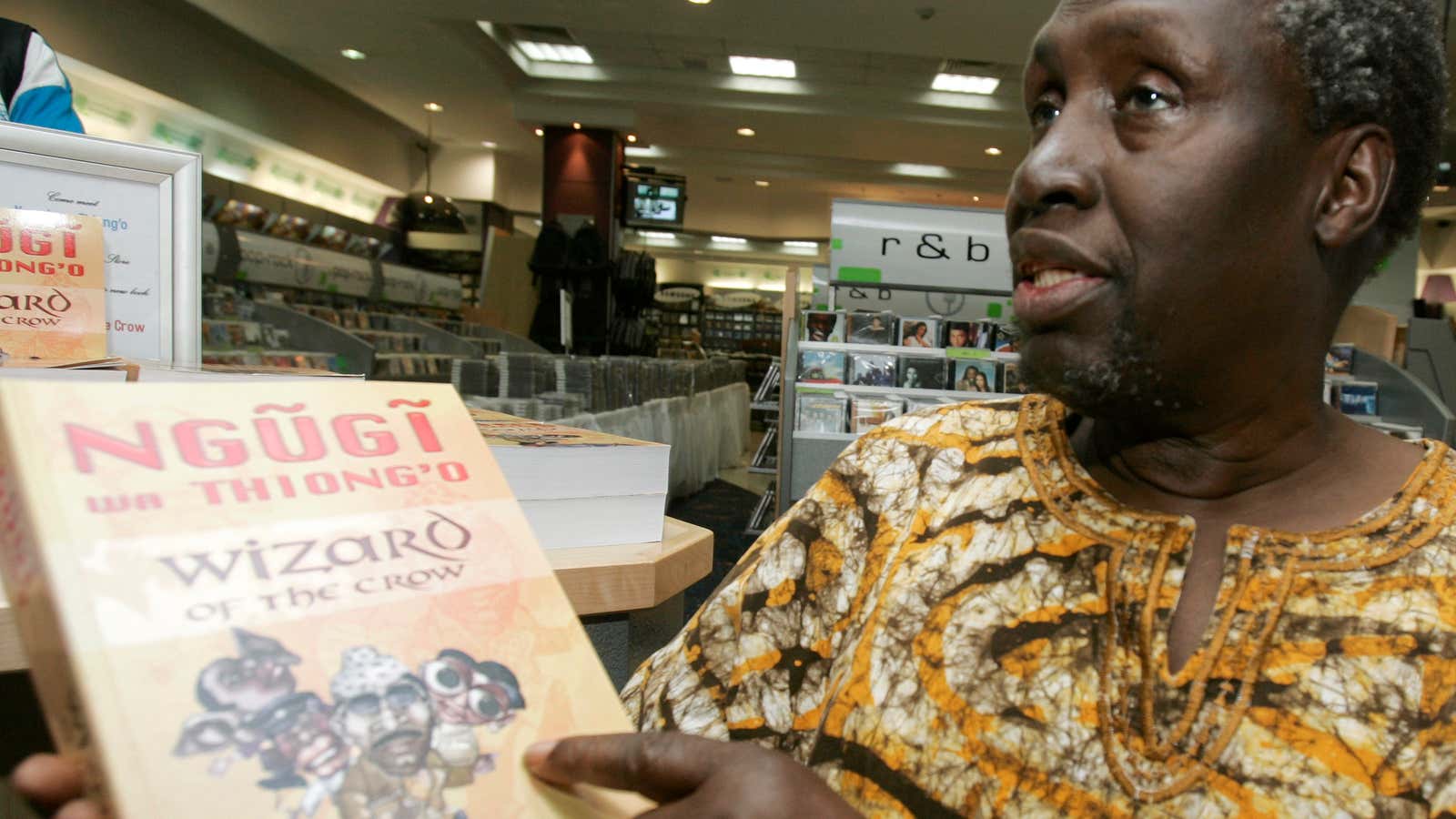

Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o visited South Africa last week, delivering public lectures at universities in Cape Town and Johannesburg. He visited campuses that were still fraught with the tensions of the Fees Must Fall movement and the ongoing debate on how to decolonize South Africa’s Eurocentric higher education system.

Late last year Ngũgĩ published “Birth of a dream weaver: A writer’s awakening” a memoir of his experiences at Makerere University in the 1960s that molded him as a writer and African intellectual. Five decades later, students poised to begin their own careers crammed into the Baxter Theater at the University of Cape Town on a Friday night (Mar. 3), to sit at the feet of one of the continent’s greatest storytellers.

Along with groundbreaking fiction, Ngũgĩ’s cannon has included scholarly work on the importance of African languages in building a post-colonial identity. It was an ideal topic as South African students challenge the remnants of apartheid in their curriculum. Just two years ago, the #RhodesMustFall student protest movement led to Cecil John Rhodes’ statue removed from its perch overlooking the University of Cape Town, pushing the decolonizing debate from campuses to suburban dinner tables.

Themed “Decolonizing the mind, securing the base,” Ngũgĩ spoke of the importance of prioritizing African languages and culture in order to dismantle Rhodes’ enduring view of the continent—raw materials waiting to be plundered from Cape to Cairo. Why, asked Ngũgĩ, were there not as many African businesses in Europe and the United States as there were western multilateral corporations represented here?

“Along with their economic and political empires, they spontaneously and consciously created empires of the mind through languages, ideologies and practices,” he explained, drawing on examples of Scottish and Irish identity to illustrate the colonial project’s effects. In Africa, this project threatened to obliterate African languages as the official and cultural tongue.

“They gave us their accents in exchange for access to our resources,” Ngũgĩ told a roaring crowd.

Part of securing the base would mean making it “cool and clever to know African languages,” he said. The moral of his story: You must know who you are, in order to take back your identity. But these pearls of wisdom threatened to get lost in the morass of anger that grips South African student politics.

About forty minutes into the lecture, a protester walked on to stage and without a sound sat between Ngũgĩ’s podium and the moderators. She held up a placard throughout the rest of the evening that read “South African education is exiling poor black disabled people.”

Ngũgĩ acknowledged the woman, but no one else did. The author finished his lecture (with only a few heckles from a man who was never allowed to speak). It was only during the question and answer part of the evening when a woman in the audience challenged moderator and well-known South African academic Xolela Mangcu. Dispensing with respectability politics, the woman accused Mangcu of creating a “boys club” on stage by ignoring the silent young woman and instead asking a male student representative to respond to Ngũgĩ.

In his defense, Mangcu said he’d given a woman the chance to speak at the Johannesburg event a day earlier, to boos from the crowd. Mangcu did not respond to Quartz’s request for comment.

Then another student asked a question—again a man—about how a conversation about decolonization could be had when the enemy was at the table. That enemy was the white people in the auditorium, some of whom shifted uncomfortably in their seats.

Smiling generously, Ngũgĩ wanted to talk to—instead of at—the young people. He wryly turned to storytelling, recalling his own time as a young lecturer in a department that hardly recognized African literature. In the minority as an African, he turned to European colleagues who shared his ideals as allies.

More radical critics may see this as reformist, trying to change the system from within rather than dismantling it completely. It’s become a rallying cry of some in the Fees Must Fall movement, who are themselves still interrogating what decolonization means, as one student representative explained.

Ngũgĩ’s lesson fell on deaf ears, though. When a white man rose next to ask a question, black students shouted him down, refusing to let him speak even as Mangcu implored them to let him. By now, the women who felt slighted by Mangcu when he ignored their raised hands, were also heckling. Ngũgĩ looked on with a slight smile, leaning back in his chair.

Exasperated, Mangcu ended the public lecture there and then, dismissing any further questions. It also silenced the voices of those who may have had an alternative view to the dozen or so hecklers. Above all, it was a missed opportunity to learn, first hand, from one of Africa’s greatest thinkers.