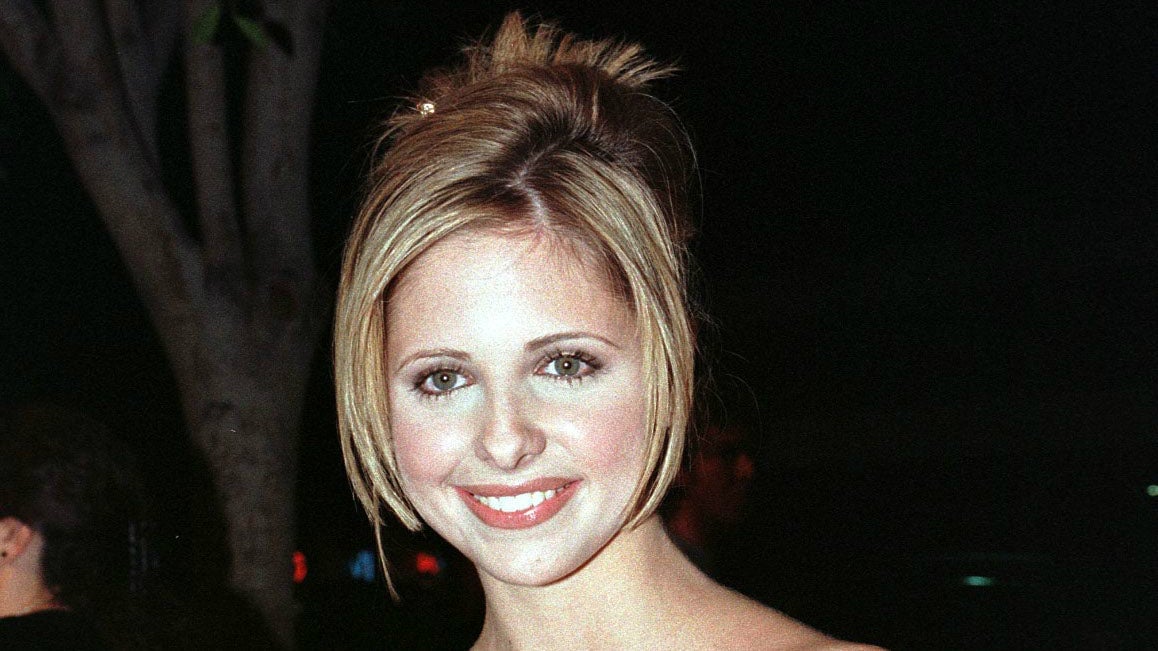

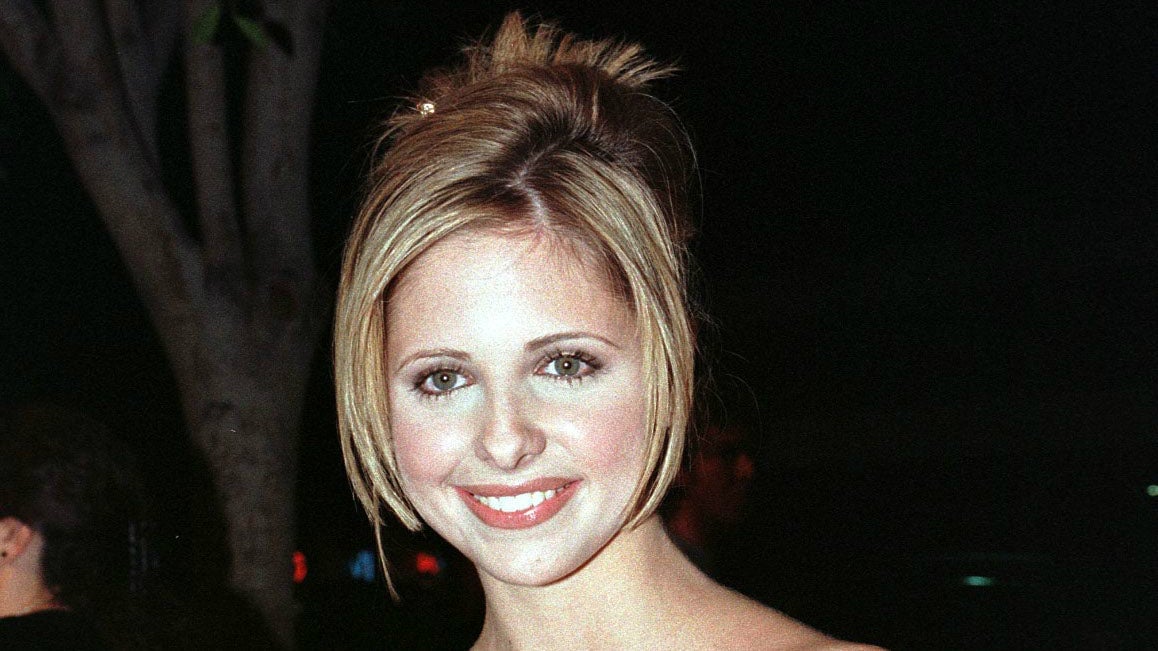

The revolutionary message of Buffy the Vampire Slayer

Something about Buffy the Vampire Slayer makes it worth returning to again and again—and it’s not the mom jeans and Cibo Matto cameos. As with any classic, the casual quinquennial binge-watch of the American show, which ran from 1997 to 2003, reliably rewards its viewers with new insights.

Something about Buffy the Vampire Slayer makes it worth returning to again and again—and it’s not the mom jeans and Cibo Matto cameos. As with any classic, the casual quinquennial binge-watch of the American show, which ran from 1997 to 2003, reliably rewards its viewers with new insights.

Two decades on, its biggest theme—the battle between pluralism and authoritarianism—resonates with more relevance than usual.

http://giphy.com/gifs/buffy-QYaK2SIoxGDja

To understand why, it probably helps to run through a brief Buffy plot overview (brace yourself for spoilers): The show is set in Sunnydale, a fictional California town that happens to sit atop the Hellmouth—a concentration of hellish energy where demons and vampires abound. (Another Hellmouth, incidentally, lies under Cleveland.) Buffy is a 16-year-old girl firmly on the cheerleading and prom-queen track. Until, that is, the cosmos anoints her the Slayer, the sole protector of humanity, with the phenomenal strength needed to fight the forces of darkness. Buffy’s monster-fighting, and the havoc that follows her, knocks her out of the cool-kid firmament, leaving her to befriend the fellow outcasts known as the “Scooby Gang,” who pitch in to fight evil alongside her.

http://giphy.com/gifs/btvs-wMf4rMBimLhEA

The show quickly outgrew its original conceit—that high school is literally hell—and expanded to focus on the “Big Bad,” a character or force of paramount evil that Buffy and company battle throughout each season’s story arc.

http://giphy.com/gifs/btvs-mcgowaniac-buffygif-2iUtLTuWfBp0k

Big Bads aren’t the scariest-looking of Sunnydale’s hellspawn. (That distinction is shared by The Gentlemen, Kindestot, the Kweller demon, and Norman Pfister.) In fact, Big Bads often aren’t even fundamentally demonic—the town mayor, for instance, or US military scientists. Or, for that matter, Buffy’s nerdy goofball best friend, Willow.

http://giphy.com/gifs/buffy-btvs-gentlemen-aKyx2h36XAZoI

No, the thing that makes them both “big” and “bad” is their quest for power, their desire for total tyranny. Their ambition is, invariably, to impose their will on all of humanity (though also, usually, to destroy it altogether). This is true from the get-go: The threat to humanity in Season 1 isn’t actually the the Master, the ancient vampire with a penchant for leather and Nehru collars. Rather, it’s his plan to conjure up an even deeper force of evil.

It’s probably no coincidence that most of the super-villains that succeed the Master don’t look like super-villains at all. After all, fangs and demony-red eyes aren’t nearly as terrifying as the qualities that define the Big Bads, who embody the ugliest of human traits—cruelty, obsession with loyalty, vengefulness, blazing conviction in their own superiority, an out-of-control temper. They want to remake reality to suit these whims.

http://giphy.com/gifs/buffy-ucIpT1SxcZIeQ

You don’t have to blur your eyes much to make out a few Big Bad-esque leaders in this historical moment—Vladimir Putin, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and Rodrigo Duterte, for example, are all about foisting their will on the people. The parallels to US president Donald Trump are unavoidable too; his temper, narcissism, and, above all, his apparent interest in upsetting liberal democratic order are classic Big Bad traits (he also shares Mayor Wilkins’ deep fear of germs). In Buffy, the super-villains plan fantastic ways of warping reality—merging dimensions or morphing into a giant lizard-demon, for example. Today’s budding authoritarians twist reality to their liking through flag-waving, control of the media, fear, and a untruths of otherworldly dimensions.

http://giphy.com/gifs/buffy-qh59hxBXlEUrC

This isn’t to call these world leaders monsters. For one thing, as I’ve mentioned, most of the Big Bads aren’t technically monsters at all. A part of what makes Buffy compelling still today is the universal truth to be found in its metaphors. Buffy’s Big Bads are cartoon ruminations on how intoxicating power can be.

There also remains embedded in the show a powerful argument for democracy as the antidote to unchecked power. At first that mainly comes from Buffy. As the show progresses, Buffy’s Slayer powers become less central, and the Scooby Gang as a whole grow increasingly key in battling both everyday devilry and the Big Bad. In the last season, Willow even figures out how to activate the powers of all potential Slayers, endowing ranks of teenage girls with superhuman abilities that had been Buffy’s alone, and underlining the point that Buffy and company find their greatest strength in sharing power, not monopolizing it.

http://giphy.com/gifs/buffy-the-vampire-slayer-8DBC1F5qARbjy

Though Buffy takes top billing, her eponymous show isn’t actually about the bad-assery of one girl superhero fighting evil, flanked by her jokey sidekicks. As hokey as it might sound, Buffy’s most affecting theme is the triumph of friendship.

The penultimate season in particular drives this point home. In its devastating conclusion, Willow becomes the Big Bad when her girlfriend’s murder sends her on an apocalyptic black-magic bender. It is Xander the ordinary-guy construction foreman, not Buffy, who saves Willow (and humanity) from her own powers.

Of course, the pluralist Scooby Gang values of shared responsibility and mutual respect always win out over tyranny in the end. Those victories come with steep costs, though—heartbreak, betrayal, and the deaths of beloved characters. Things get bleak. But while Buffy, as the Slayer, has a sacred duty to stop Big Bads, no one else in the Scooby Gang does. They fight in solidarity—out of commitment to each other, but also to the order they’ve sacrificed so much to protect.

http://giphy.com/gifs/buffy-the-vampire-slayer-happy-birthday-sarah-michelle-gellar-14oItKdLPXb8Qg