The UK government will teach eight-year-olds mindfulness to tackle spike in kids’ mental health problems

In the West, mindfulness, the practice of bringing one’s awareness to the present moment, is no longer the stuff of yoga classes and corporate retreats.

In the West, mindfulness, the practice of bringing one’s awareness to the present moment, is no longer the stuff of yoga classes and corporate retreats.

The British government will fund (pdf) randomized control trials in more than 200 schools across the country to see whether mindfulness effectively reduces stress and promotes wellbeing among eight to 12 year olds, and separate programs to teach teens about anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues.

Preventative programs will be rolled out at 100 primary schools and 50 secondary schools this summer, teaching mindfulness, protective behaviors—i.e. teaching kids how to recognize signs of not feeling safe and what to do about it—and relaxation and breathing-based techniques.

According to the Sunday Times:

In typical mindfulness lessons, children are taught to think of disturbing thoughts as “buses” that will move away. They also learn the 7/11 exercise, breathing in for seven seconds and exhaling for 11 seconds, to reduce anxiety. Relaxation and breathing classes will also be tested.

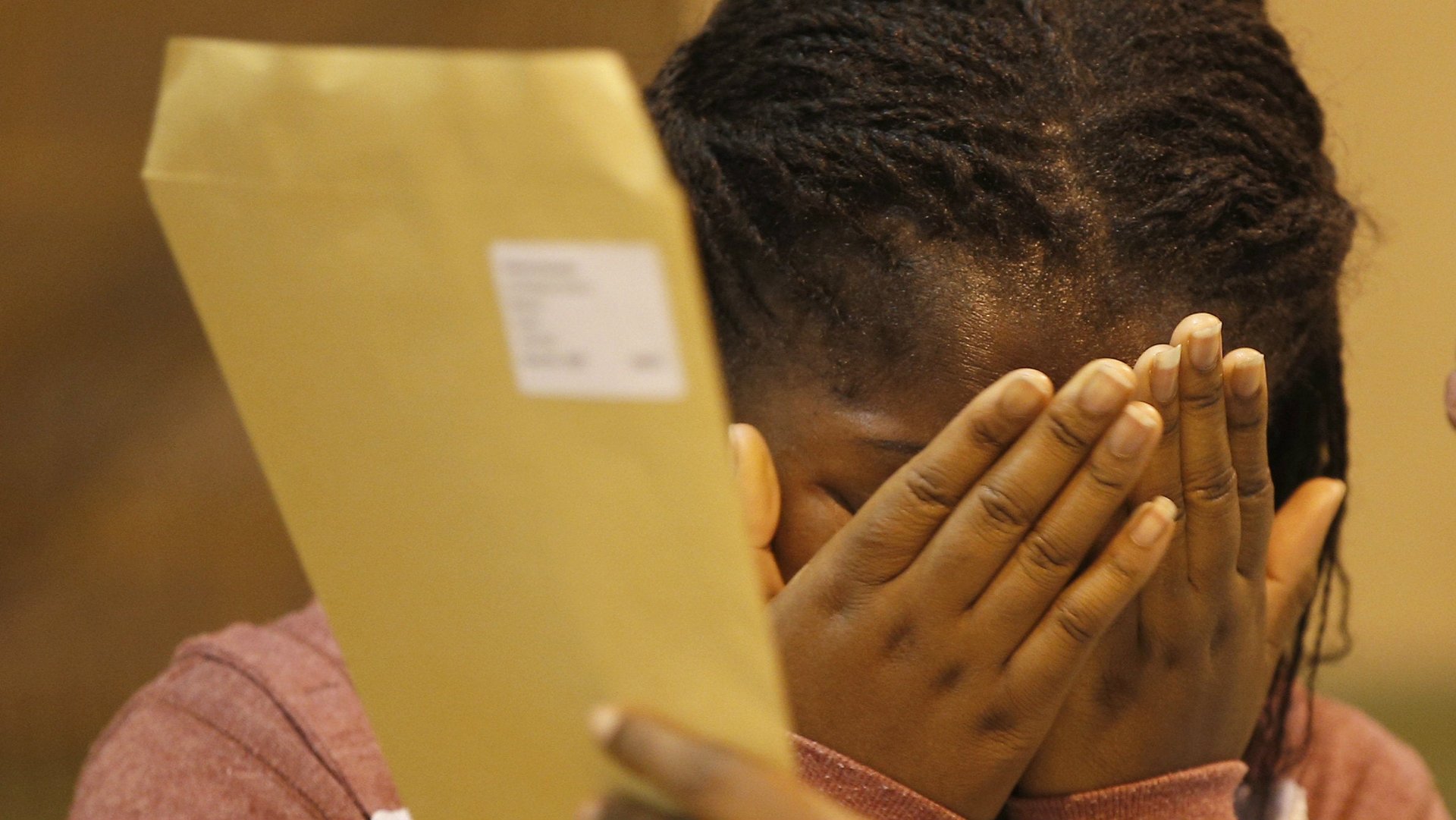

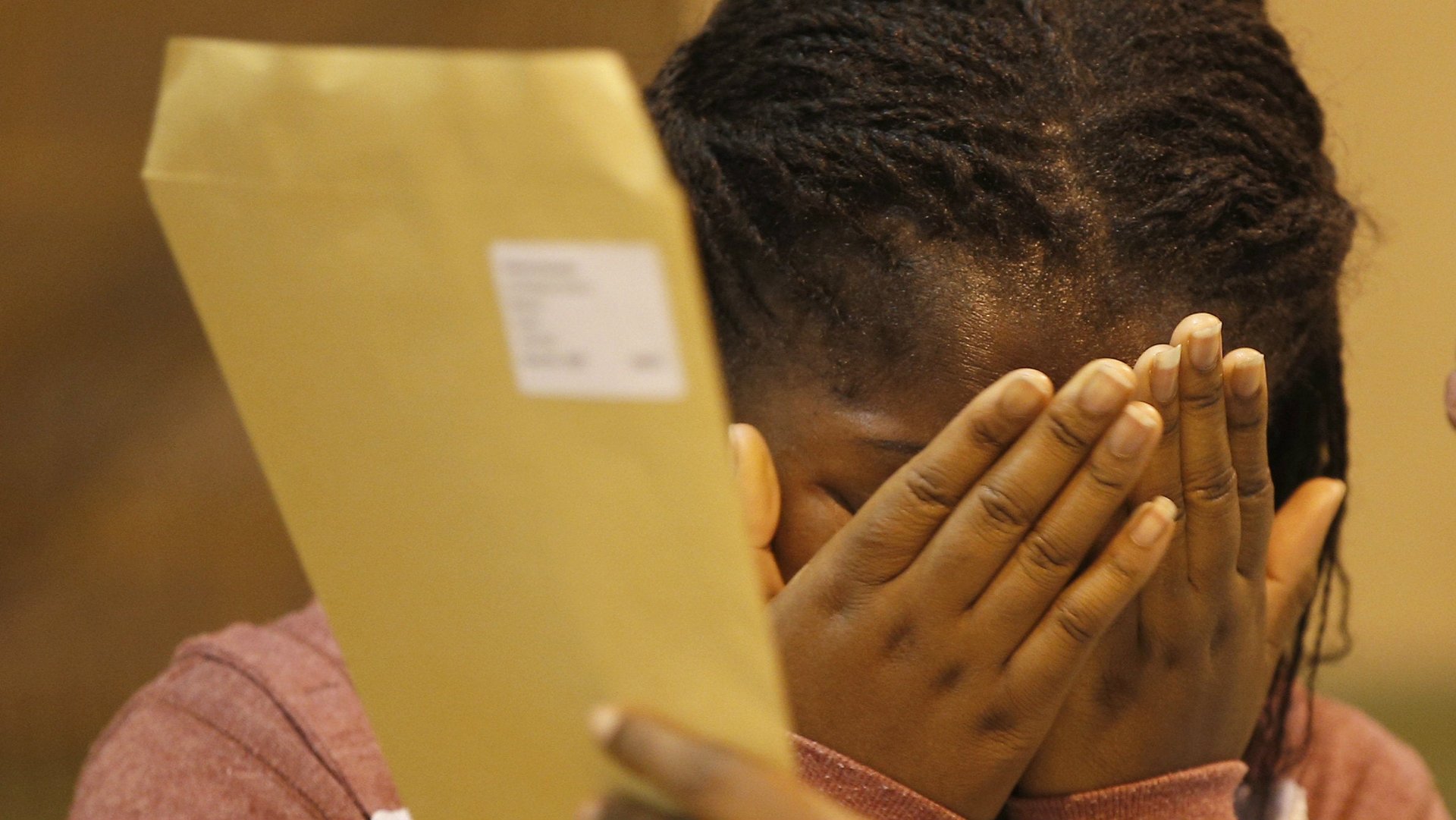

Schools around the world are ratcheting up the pressure on kids to perform better on math and reading skills. But some worry that the pressure of that, in conjunction with kids’ headlong dive into all-things-internet and social media, has created a perfect storm of pressure, resulting in rising levels of kids’ depression and anxiety. Some have responded by implementing some kind of mindfulness curricula.

A recent report by the UK’s Institute for Public Policy Research said that three children in every class have a clinically diagnosable mental health condition and that 90% of principals—called head teachers in the UK—have reported an increase in mental health issues over the past five years. The group recommended that schools have a child or adolescent mental health professional on site at least once a week.

Teachers aren’t the only ones who’ve noticed the problem. A survey of 300 doctors who are part of the National Health Service (NHS) found that self harm among 11-18 year old children was up 61% over the past five years, with 83% reporting that services to help these kids were either ‘inadequate’ or ‘totally inadequate’, the Guardian reported. Richard Layard, a government advisor who is working on mindfulness trials in 26 schools, told the paper it was time to measure something other than just academics:

“The development of the character of children is an incredibly important issue,” said Layard, who is also a professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). “If you really want schools to take the wellbeing of their pupils as an important goal, there has to be a way of measuring that.”

In January, British prime minister Teresa May said, “If you suffer from mental health problems, there’s not enough help to hand.”

British teens seem to faring worse than others. In 2016, the World Health Organization found that 15-year-olds in England and Wales were among the most unhappy in the world; only teens in Poland and Macedonia reported lower levels of satisfaction with their lives.

Julie Lynn-Evans, a UK-based psychotherapist, said the decision by the UK government was “fantastic” but worried that it might not go far enough in recognizing the harmful effects of the internet on kids, and also, making sure the kids understand why they are practicing mindfulness. “The kids need to know why it’s important for them to be doing it, or its just another thing for them to do and another target for the teacher to reach,” she said.

Many schools have their own mindfulness initiatives but may not track the effectiveness of them (especially as compared to kids not getting the programs, which is how randomized control trials work). The Education Endowment Foundation(EEF), a UK-based non-profit organization that wants to close the gap between family income and educational attainment, is testing similar programs, though many are aimed at trying to help kids reduce anxiety to improve school performance. Some of their programs include:

- FRIENDS, a 10-week intervention that to help teach young people practical skills to identify and manage their anxious feelings; to identify unhelpful anxiety increasing thoughts and to replace them with more helpful thoughts; and how to face and overcome their problems and challenges.

- Developing healthy minds in teenagers, a set of programs using cognitive behavior therapy to improve pupils’ wellbeing resilience and motivation.

- Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS), a school-based social and emotional learning (SEL) curriculum that aims to help children in primary school manage their behavior, understand their emotions, and work well with others.

According to the government’s proposal, the aim of the latest trials is “better information about effectiveness and implementation to any school that might be considering offering this sort of activity.”