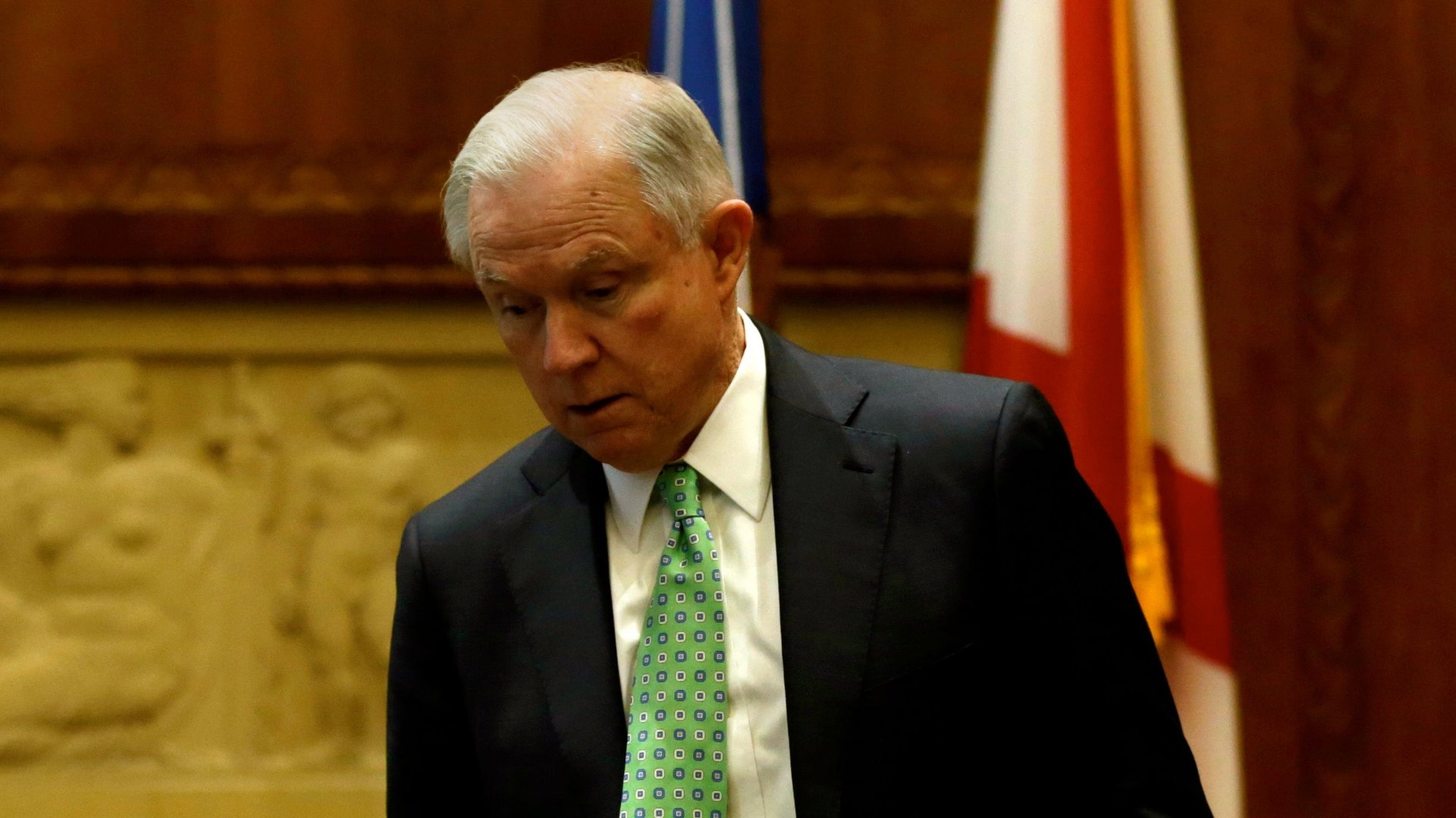

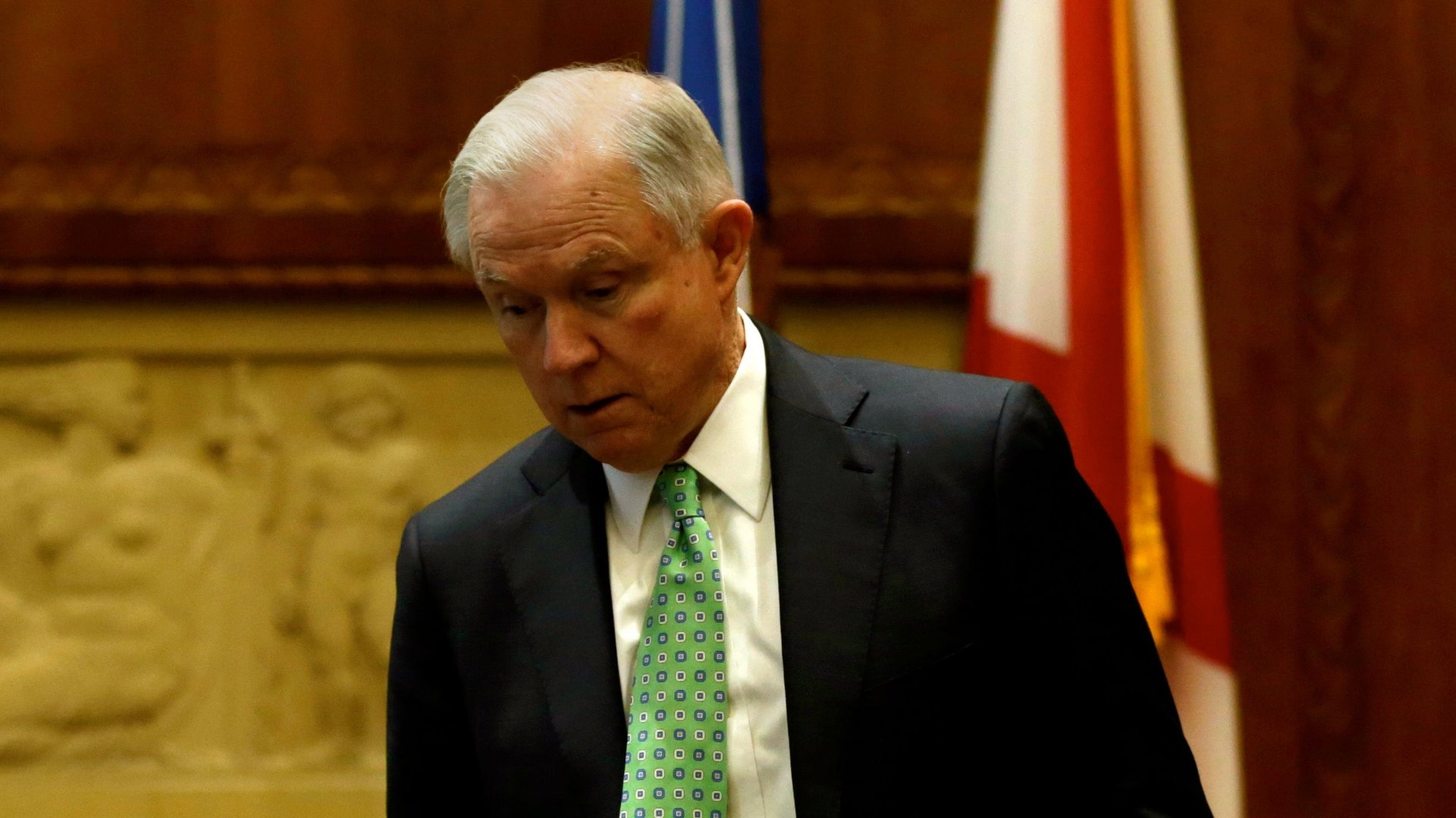

For US attorney general Jeff Sessions, the future of marijuana looks just like the past

US attorney general Jeff Sessions knows that the country is in the throes of an opioid epidemic. Sessions also knows that many state legislators—and scientists—believe legal marijuana could help fix it. He just really, really hates that idea.

US attorney general Jeff Sessions knows that the country is in the throes of an opioid epidemic. Sessions also knows that many state legislators—and scientists—believe legal marijuana could help fix it. He just really, really hates that idea.

“I am astonished to hear people suggest that we can solve our heroin crisis by legalizing marijuana–so people can trade one life-wrecking dependency for another that’s only slightly less awful,” Sessions said in a speech to federal, state, and local law enforcement agents in Virginia this week. He continued:

“I realize this may be an unfashionable belief in a time of growing tolerance of drug use. But too many lives are at stake to worry about being fashionable. I reject the idea that America will be a better place if marijuana is sold in every corner store … Our nation needs to say clearly once again that using drugs will destroy your life.”

If that rhetoric sounds familiar, it’s because it is. In 1971, Richard Nixon declared a “war on drugs” that went on for decades with little interruption. In 1977, during president Jimmy Carter’s tenure, the Senate Judiciary Committee voted to decriminalize marijuana possession (up to an ounce) for personal use, but when Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, the war on drugs intensified again.

In 1983, Los Angeles police and schools created Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE), an awareness program that soon spread nationally. In 1986, then first lady Nancy Reagan urged Americans to be “unyielding and inflexible” in their opposition to drug use, launching the famous ”Just Say No” campaign. The slogan was coined from a response she gave kids at a school in 1982, when asked what to do if offered drugs.

Sessions credits prevention campaigns like DARE and “Just Say No” with educating would-be drug users and spurring a decline in drug abuse nationwide. During a youth summit on opioid addiction in New Hampshire this month, he told an audience that, because of such efforts, “people began to stop using drugs. Drug users were not cool.”

That is not clearly the case, however. In 2014, Scientific American reported on a meta-analysis of data from 20 controlled studies of DARE’s effectiveness that found little difference in drug use between young people who went through the program and those who did not. In a 1999 study of DARE, also noted by Scientific American, Purdue University clinical psychologist Donald Lynam came to similar conclusions. He suggested that parents and teachers believe in the efficacy of prevention campaigns because “it makes intuitive sense” to warn kids against drug use, even if the data doesn’t support that approach.

The idea behind “Just Say No”—unyielding inflexibility on all drug use—also appeals to those who consider marijuana a “gateway drug” to harder substances like heroin and opioids. (While hard drug users do tend to smart out smoking pot, the vast majority of those who try pot don’t turn to hard drugs).

But total abstinence is going to be difficult to sell in 2017, as Sessions has pretty much admitted. Cannabis is finding widespread acceptance in the US. There’s already evidence that people are ditching opioids (and beer) for pot. Legal marijuana has been linked to fewer traffic fatalities, and scientists are pushing to expand the research supply so they can speed up clinical study of pot’s medical benefits. Sessions’ vision for the future may be the past, but few seem to want to go back there with him.