Why even a women’s underwear startup couldn’t create a good culture for women

It’s become something of a tradition: Hot new startup enthuses the public, wows the media, charms investors, turns out to be exploiting its employees, and goes through a spasm of contrition in which the chastened founder publishes an apologetic yet defiant mea culpa.

It’s become something of a tradition: Hot new startup enthuses the public, wows the media, charms investors, turns out to be exploiting its employees, and goes through a spasm of contrition in which the chastened founder publishes an apologetic yet defiant mea culpa.

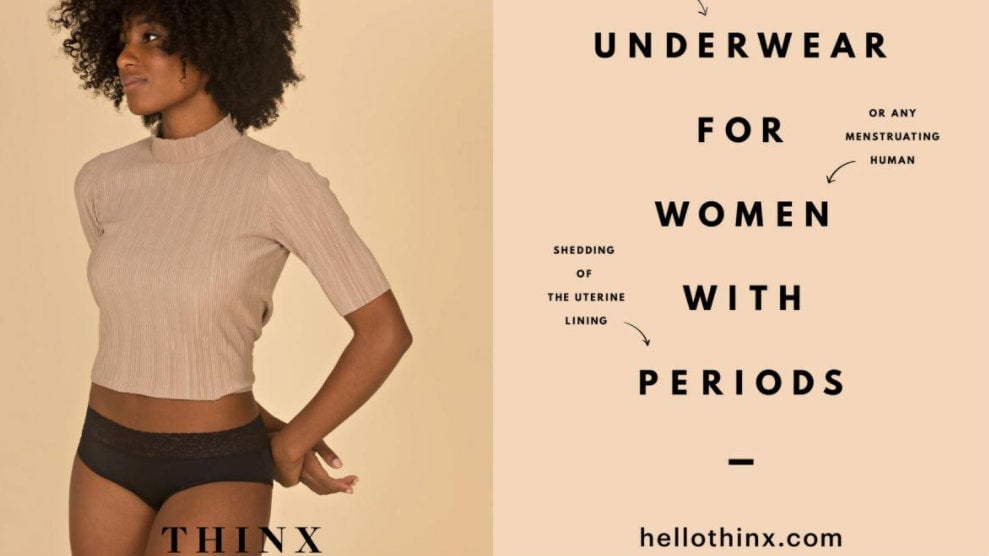

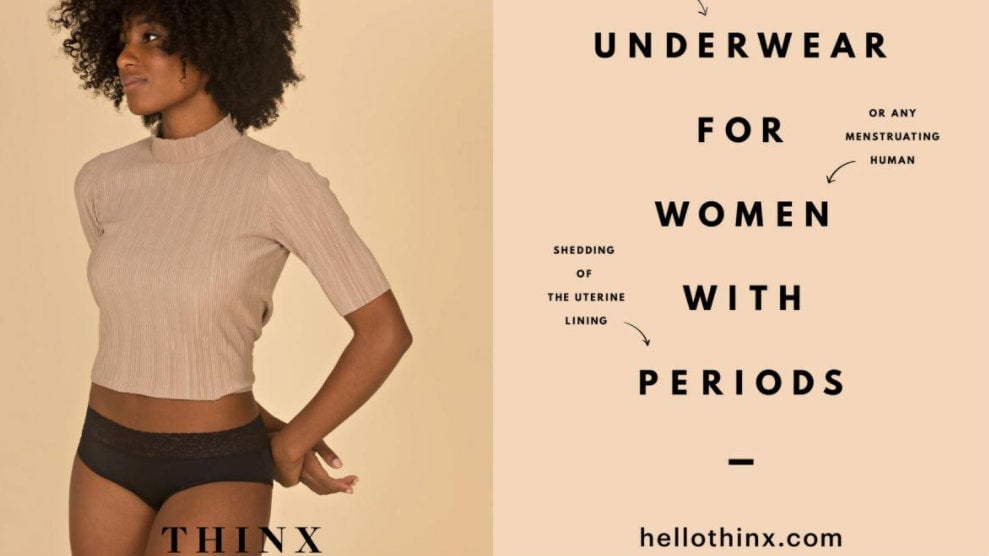

The latest example is Thinx, which makes high-tech underwear for women to wear during their menstrual cycles. In an exposé published this week, Racked portrayed a company at which workers are underpaid and have few benefits and perks. Ten of its 35 employees have reportedly quit since January.

Employees told Racked that attempts at salary negotiation were rebuffed and they were told to embrace gratitude instead. One female employee said she couldn’t even afford birth control: “What does that mean if we’re at a feminist company and I can’t afford to keep myself safe and protected?’”

The article claims that two of the few white male employees at the company were the only ones to successfully negotiate higher salaries. That was especially embarrassing for a company run by a woman, Miki Agrawal, with women’s wellbeing as its mission.

Agrawal, who stepped down as CEO amidst the news—though she’ll remain at the company—wrote on Medium that she regrets not hiring an HR manager: “I didn’t take time to think through it.”

In an email to Quartz, she further explained that Thinx operated like many startups, evolving as it grew. She denied the claim about gender preference in salary negotiations and cited the company’s maternity leave policy, criticized in the Racked story—only two weeks at full pay—as an example of how the company is evolving.

“We haven’t had any pregnant women until now which is why we didn’t really have a real policy in place for that. Like any start up when faced with something new, you do your best in solving it as it arises. Our first employee just gave birth (10 days ago) and she is getting 5 weeks paid leave plus we found out that she can take an additional 2 weeks on paid disability leave too. And then we’ll figure out a system where she can either work from home for part of the time or we were planning on getting an in-house nanny for the office.”

Like a lot of startup founders, Agrawal focused on growth above all. And it worked: Thinx is on the map. The company has been featured by most every major publication, thanks in part to a viral news story around its controversial ads in New York City subways. Fast Company listed it as one of the most innovative companies of 2017. Last month Agrawal told Bloomberg that her goal was to become the “No. 1 feminine hygiene brand in the world.”

But glowing articles about disruption and innovation often hide the fact that working for a startup typically isn’t glamorous. In their early years most are just struggling to survive.

Even Tony Hsieh, CEO of the online shoe retailer Zappos and something of a guru on company culture, found it difficult to replicate the advice from his own company-building manual, Delivering Happiness, at his next venture, Downtown Project. (Hsieh wrote the foreword to Agrawal’s company manual, Do Cool Sh*t: Quit your day job, start your own business, and live happily ever after.) A more generous company culture is something that typically develops years later, with more funding and stability.

The only things startups really have to sell early employees is a mission and the opportunity for personal growth. Yet many have over-promised utopian working conditions to attract recruits, and now the backlash over the gap in expectations is growing.

Silicon Valley’s unicorn-obsessed culture has not helped in this regard. And when only about 4.2% of senior partners at top venture-capital firms are women, it’s no surprise that even a company run by and for women isn’t under much pressure to behave like one. The story of Thinx simply shows that the structural problems within the tech industry still apply, no matter who is in charge.