Why humans know Obama is not planning a coup but Google does not

Working on a quality score for publishers and authors is an effective way to mine quality from the web—and to fight fake news. To do this, we need to find, combine, and weight the right “signals.”

Working on a quality score for publishers and authors is an effective way to mine quality from the web—and to fight fake news. To do this, we need to find, combine, and weight the right “signals.”

Recently, publishers and large distribution platforms finally decided to address the fake news problem. Most of their efforts entail connecting the avalanche of content to one or more fact-checking outlets such as Politifact, Snopes, or FactCheck.org.

In France, Le Monde created Decodex, a search engine that scores the reliability of websites. It works, sometimes. I tried entering sites referenced by Outbrain, a robust source of crappy news that plagues Le Monde’s web pages. None of these were known to Decodex. In due fairness, the system is less than two months old and it is improving fast. Weeks before a French presidential election marked by an unprecedented push of the extreme-right, detecting fake news is a burning issue. With 42 others French news organizations, Le Monde also participated in a Google-backed initiative called CrossCheck (see this Google Labs story on Medium).

On platforms, Facebook recently rolled out a system that also relies on third party fact-checkers and flags “disputed news” (see below):

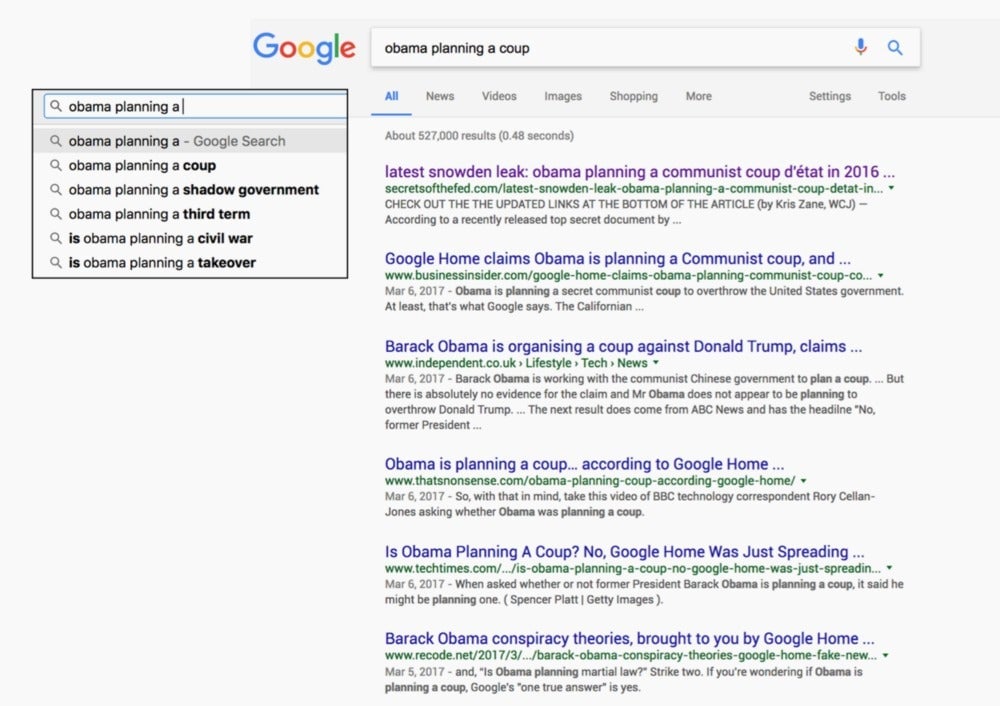

Not only is Facebook working with multiple publishers, but Google also keeps refining its search algorithm. It’s still a work in progress, though. Here is what I got this weekend when typing “Obama planning”: the first autocompletion came up as “…planning a coup” with more than half a million results:

The fake news phenomenon is like a bio-engineered plague: it spreads to all countries as specialized outlets make it their business to churn false information on an industrial scale. It hits democracies at a moment when professional media see their business models challenged from all sides.

As worthy and necessary as they are, initiatives to detect fake news tackle symptoms more than causes. They don’t address the issue of quality news in a broader sense and, moreover, they don’t scale. Thus it is a big problem for distribution platforms (social and aggregators) which deal with a firehose of thousands of stories per day (keep in mind that Facebook distributes 100 millions links a day!).

My work at Stanford’s John S. Knight Fellowship focuses on surfacing quality from the web in a scalable way. It plans to solve the quality problem indirectly, by triangulation as opposed to straightforward detection.

Let me use the quest for exoplanets as an analogy. Today’s astronomers cannot see a faraway earth-like planet. Rather, they deduct their presence and their structure from indirect observations. For instance, they will look at what is called a “transit”—when a planet passes between earth and a distant star, its brilliance dims infinitesimally. They will also look at subtle variations in the infrared emissions of the star and its surroundings; or light variation due to gravitational field alteration; or even the minuscule deviation of a star’s center of gravity due to a presence of a massive object nearby, like in this animation:

Coming back to the news business, a close look at a precise set of signals can reveal a lot about journalistic quality and, as a corollary, about the risks of encountering fake news.

In the end, it boils down to assessing the reputation of both publishers and authors. They won’t admit it publicly, but Google, Facebook, and other large news distributors already rely on quality scoring variants.

Building such indices is a super sensitive issue in the news industry. Their acceptability also depends on presentation. A ranking of thousands of publishers and journalists would certainly raise eyebrows, much less so for a kind of whitelist that would put news producers in different buckets of reliability. Or think about some kind of TSA Pre, the American pre-check system in airports for passengers.

Here is how it could be done.

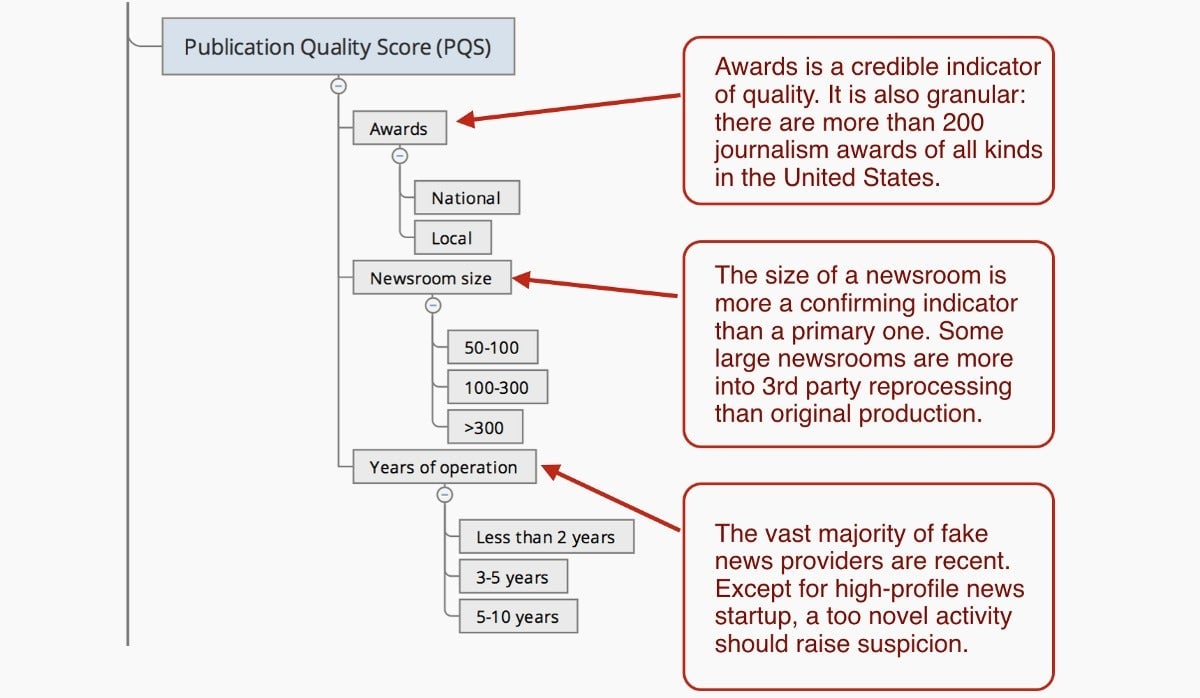

To evaluate a publisher’s quality, a look at its relative size and history—journalism prizes, years of operation—already provides useful information as explained below:

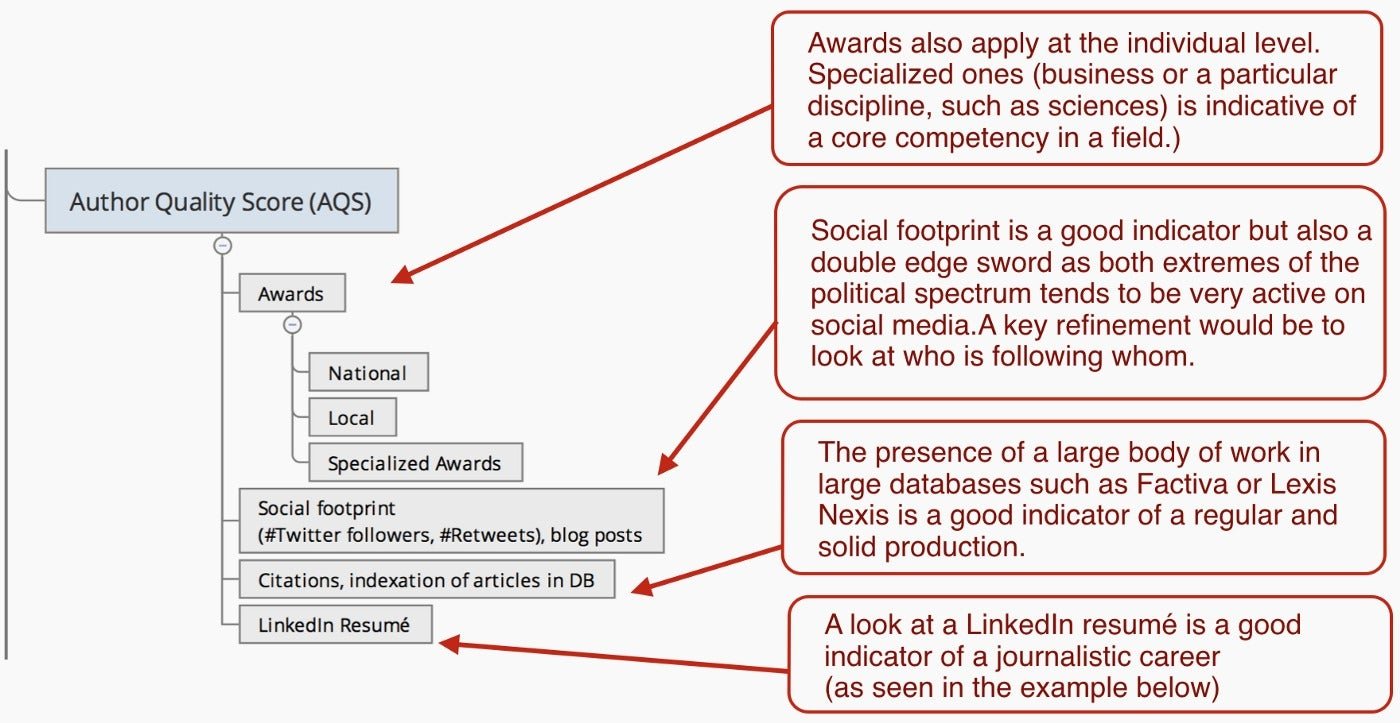

Authors could “enjoy” the same scrutiny:

As always, the devil lies in the details: not all databases have APIs or can be legally scrapped; false positives do emerge; résumés are made up, etc. But at least it is a starting point, and it’s definitely worth trying (more in about two months, as I’m dealing with a corpus of ten thousands of stories collected over 500 US-based web sites and 850 RSS feeds).

This also needs to be supplemented with other signals such as the propensity of a publisher, or of an author, to often be at the origin of a news cycle—a news cycle that will last long enough to be reliably impactful (for instance, regional dailies tend to break news on a more predictable basis).

At the story level, some indicators also reinforce or weaken the “Publication Quality Score.” As an example, a lengthy story (presumably a positive sign) scattered with photos that are unattributed, or coming from a stock provider, will raise suspicion. This is to be opposed to a publisher that opted to produce its own iconography as a part of a significant journalistic effort. Other signals to consider involve semantic structure and density of a story, or hints of SEO manipulation.

Combining signals collected automatically on large samples also implies understanding how they should be weighted against each other.

My current model involves about 40 signals and sub-signals. Even such relatively small number makes the weighting assessment a delicate task. When I showed various iterations to computer science people here at Stanford, they all suggested that a deep learning approach could solve the weighting issue. A set of articles labelled as “good” is fed into a neural network that will teach itself to accurately label another vast corpus of articles. This is similar to the process used by a neural network to identify a cat in a huge pile of images of animals: the network is trained by being first exposed to large quantities of cat pictures.

Problem is, in order to be effective, the training set (i.e. the number of articles labeled as “good”) needs to be huge—in the tens of thousands. While it is relatively easy to label 30,000 images of cats (using crowdsourcing or drawing from existing bases), no one ever tried to label a set of just a few thousands of news stories. A long, interesting way lies ahead…