For humans to stand a chance in the age of artificial intelligence, we need to join the other team, at least in Elon Musk’s view.

The Tesla and SpaceX CEO dreams of humans evolving into cyborgs with augmented intelligence. That vision took a step forward on Mar. 27 when the Wall Street Journal reported Musk had co-founded Neuralink, a medical research company dedicated to building a seamless brain-computer interface.

Founding team member Max Hodak confirmed Musk’s involvement in the “embryonic” company, which was registered in California last July. Neuralink is already raiding research labs and universities for engineers and neuroscientists to build its technology, according to the Journal. Its goal: upgrade the interface between the digital world and human brains.

Researchers have compared today’s interfaces—screens, keyboards, and even crude direct brain implants—as dial-up modems compared to the lightning-fast connections our brains are capable of managing if we didn’t need to route all the data through our senses.

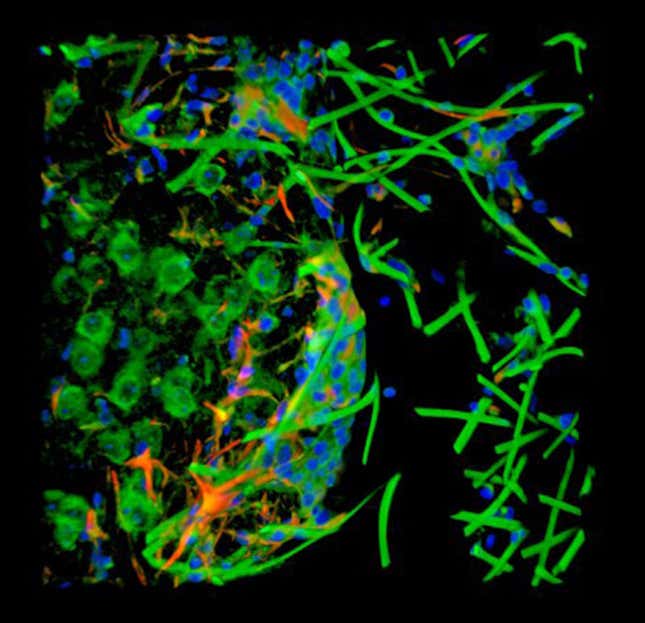

Musk is pursuing this high-bandwidth connection through a technology called “neural lace.” The term was coined by science-fiction novelist Iain M. Banks, who wrote a series about members of a galactic ”Culture” civilization who had a “neural lace” allowing them to translate thoughts directly into computer commands, alter neurochemistry, and even restore consciousness after death. Musk’s version appears to be about seeking enhanced cognitive abilities by adding vast networks of tiny electrodes to the brain. Over time, these fuse with brain cells in a presumably superior mesh of human and artificial capabilities.

While the tech sounds outlandish, brain-computer interfaces are already leaving the lab and entering the market. Devices such as BrainGate’s wireless receiver can translate electrical activity in brain cells into movement of a cursor or robotic arm. Yet the technology is still bulky and confined to limited areas of the brain. A full-on mesh envisioned by Musk would exponentially increase the scope and capability of such devices.

In 2015, scientists publishing in Nature Nanotechnology reported successfully injecting an ultra-fine mesh into mice brains. Thousands of scientific articles on digital connections to human and animal brains have been published since then. The military announced it was pouring at least $60 million into figuring out how to communicate with individual neurons in the human brain, and the 20-person startup Kernel is spending more than $100 million to develop related technology.

For now, digital-brain interfaces are being pitched as a way to monitor brain activity, enhance cognition, treat brain disorders and restore movement to paralyzed limbs and to control prosthetics. A neural lace-style product is still years away—even on Musk’s notoriously ambitious timelines. Musk eventually hopes the technology will let humans stay ahead of machines with superior intelligence and agency (not that all computer scientists believe machines will ever pose a threat).

Musk co-founded the non-profit OpenAI in 2015 to help design “digital intelligence in the way that is most likely to benefit humanity as a whole.” Helping humans become cyborgs offers another safeguard against an AI run amok. “I don’t love the idea of being a house cat, but what’s the solution?” Musk said at Vox Media’s Code Conference in California last year. “I think one of the solutions that seems maybe the best is to add an AI layer [to humans].”