The US can’t figure out how to measure the size of its Hispanic population

The US Census Bureau has a problem. When asked to identify their race, Americans increasingly say that they are “some other race,” an unhelpful distinction for statisticians. “We are concerned that if no other changes are made to the way we collect data on race and ethnicity… that the ‘some other race’ population could become the second largest race group in the 2020 Census,” says Nicholas Jones, the Director of Race and Ethnic Research at the bureau.

The US Census Bureau has a problem. When asked to identify their race, Americans increasingly say that they are “some other race,” an unhelpful distinction for statisticians. “We are concerned that if no other changes are made to the way we collect data on race and ethnicity… that the ‘some other race’ population could become the second largest race group in the 2020 Census,” says Nicholas Jones, the Director of Race and Ethnic Research at the bureau.

The Census Bureau considers this problematic because their stated goal is to allow people to self-identify into a recognized category. The vague “some other race” category was already the third most commonly chosen race option after “white” and “black” in 2010:

What’s going on? Primarily, it’s a result of America’s growing Hispanic population.

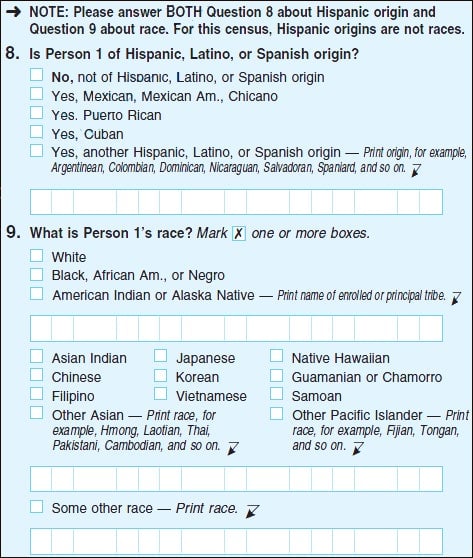

Since 1970, the census has asked two questions about the amorphous concepts of race and ethnicity. The first is about whether a person is of Hispanic origin, followed by a second about race. These questions assume that people who are Hispanic will also identify with another of the race options. But in 2010, 37% of Hispanics didn’t see themselves as either black, white, or any of the other races on their census forms. In both 2000 and 2010, 97% of the people who identified as “some other race” also identified as Hispanic.

To a certain extent, this is nothing new. A large percentage of Hispanics have long said that they are “some other race” in the census, but since the Hispanic population used to be smaller, this wasn’t a big factor in the overall results. But the Hispanic population has more than tripled in the US since 1970, and the number of people in the census identifying as “some other race” has grown in concert.

For the 2020 census, the bureau is proposing to combine the two race and ethnicity questions into one: “What is [your] race or ethnicity?” Respondents will then be able to choose as many options as they like from the following list: White, Hispanic, Black, Asian, American Indian, Middle Eastern or North African, Native Hawaiian, and some other race. (“Middle Eastern or North African” is a new addition also intended to reduce the “some other race” responses.)

In 2015, the Census Bureau tested this new question in the field. It found that it reduced “some other race” to less than 0.5% of all responses. The revamp also led to fewer respondents saying that they are white, and slightly more people identifying themselves as Hispanic.

This is not the first time the Census has adapted its approach to race and ethnicity. The US has collected data on race since 1790. From 1790 to 1810, the only options were slave, free White, and other free persons—the government added “free colored persons” in 1820. It was not until 1860 that the bureau included Asian and American Indian as categories. The Pew Research Center put together an excellent historical timeline that highlights the government’s fluid view of race and ethnicity. As these identities grow ever more complex, the number crunchers are continually playing catch-up.