Xi Jinping is angling to fill the world leadership void left by Trump. Here’s a reality check

The first meeting between US president Donald Trump and Chinese president Xi Jinping today (April 6) brings together two men who have been sending the world contrasting messages in the last few months.

The first meeting between US president Donald Trump and Chinese president Xi Jinping today (April 6) brings together two men who have been sending the world contrasting messages in the last few months.

As Trump turns inward with his “America First” policy, Xi has vowed to set an example on issues from free trade to climate change. Although Xi has never called out Trump or criticized his policies directly, the Chinese leader has managed to burnish his image by positioning himself as the inheritor of America’s leadership role, in particular through a high-profile coming out speech at this year’s Davos shindig.

Not so fast. A look at Xi’s rhetoric on a range of issues suggests that even if people want a leader to step into the vacuum left by America, Xi is not it—yet.

Free trade

Rhetoric: Protectionism is “like locking oneself in a dark room,” said Xi during his debut at Davos in January. A few days later at his inauguration, Trump said that “protection will lead to great prosperity and strength.”

During his first week in office, Trump pulled the US out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), former president Barack Obama’s signature multilateral trade pact, as he promised. Last month China joined trade talks with 12 TPP member states in Chile, although it insisted that the focus was on greater cooperation in the Asia-Pacific region, rather than the trade pact itself. China is also a key supporter of a TPP alternative known as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which notably excludes the US. The recent rollout of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the cross-continental One Belt One Road economic development plan also demonstrate Xi’s ambition in leading and reshaping the global economy.

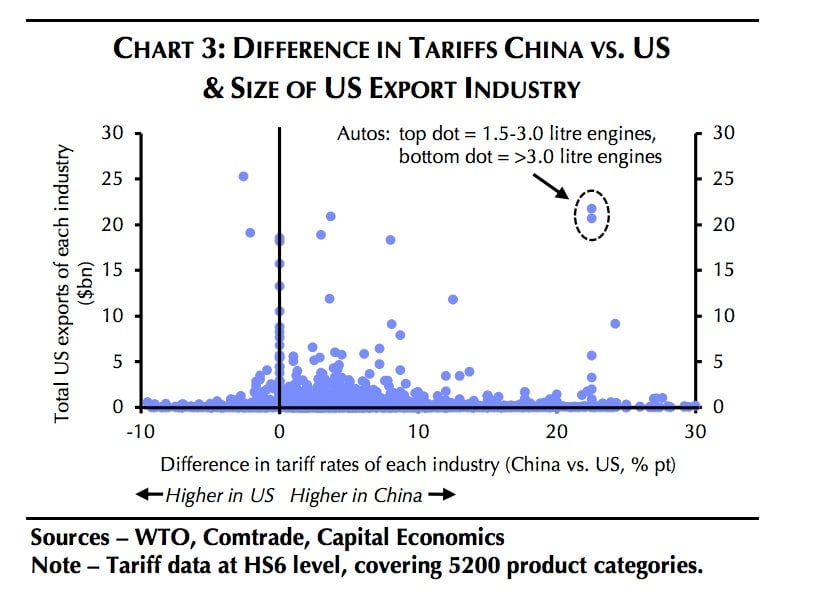

Reality: China has gradually lowered its tariffs over the past decade. But average tariff rates in China remain substantially higher than those in developed economies. Analysts at Capital Economics recently made this chart with the horizontal axis illustrating how much China’s import tariffs exceed America’s for 5,200 product types, each represented by a dot. The vertical axis shows how important an export industry is for the US. For example, as Quartz has explained, the auto sector is a large export sector for the US, with a significant tariff disparity with China.

China’s high tariffs are not out of line compared with other emerging markets. But what’s more alarming is Beijing’s preferential treatment of Chinese firms in high-end sectors that it is trying to move into, as shown by recent trade disputes brought to the World Trade Organization against Chinese policies in sectors including aircraft, wind power equipment, and automobiles.

“China is not acting so differently from how other powerful economies acted when they were developing,” said Capital Economics. “But it undermines the idea that China is wholeheartedly a supporter of free trade.”

International security

Rhetoric: “I don’t want to be the president of the world,” Trump told American building-industry representatives this week. China should take the lead in shaping a “new world order” and safeguard international security, Xi said at a national security meeting in February.

Reality: Beijing has shown little interest to lead on international security challenges; moreover, it appears that Beijing is using its ambitious-sounding rhetoric to defend its own security interests.

In February, Russia and China vetoed a United Nations Security Council resolution on sanctions for Syria over the alleged use of chemical weapons by the Assad regime. China has vetoed Syria-related action at the UN six times. Amnesty International said that Russia and China’s latest vetoes ”have displayed a callous disregard for the lives of millions of Syrians.”

High on the agenda of the Trump-Xi summit is North Korea’s nuclear threat to the Asia-Pacific region. On April 5, the rogue state launched yet another projectile missile toward Japan, after Trump said in an interview with the Financial Times (paywall) that he is ready to solve the problem of Pyongyang with or without Beijing’s help.

Another issue of high importance to the meeting is the South China Sea. In recent years Beijing has steadily built and fortified positions in the disputed waters, despite an international tribunal ruling against its sweeping claims in the sea. There are concerns that unless China’s island-building in the region is challenged, the sea will eventually become a “Chinese lake” by 2030.

Climate change

Rhetoric: “The concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese,” wrote Trump in a 2012 tweet, one of the many insane things he has said over the matter. “The Paris Agreement is a hard-won achievement which is in keeping with the underlying trend of global development,” said Xi in his Davos speech, referring to the historic climate-change deal that Trump has promised to cancel, but later said that he still has an “open mind” on.

Last week Trump signed an executive order to roll back Obama’s environmental regulations, though he didn’t mention the Paris accord. In response Beijing reaffirmed its commitment to the agreement.

Reality: China is responsible for about a fifth of all greenhouse-gas emissions in the world, having surpassed the US as the top polluter since 2006, and its continuing reliance on burning coal is producing some of the most noxious pollution seen in the world.

Nor has the US ever really been the leader on climate change, a role that has largely fallen to European governments. But there are signs that China is becoming more vocal, and even willing to indirectly call out the Trump administration’s dereliction of climate-change responsibility. In terms of real action, China in 2015 committed to cutting its emissions per unit of GDP by 60-65%. In both 2014 and 2015, it was the world’s top investor in new renewable-energy infrastructure, and it is taking steps to close down coal-burning plants in the country.

Immigration

Rhetoric: Immigration costs American taxpayers ”many billions of dollars a year,” said Trump in a February speech to the US Congress, inaccurately citing a report (paywall) to back up his anti-immigration policies. Relaxing permanent residence rules for foreigners in China “serves the nation’s talent development strategy,” Xi said in the same month calling for a reform in the immigration system. Last week, the Trump administration said that not all computer programmer positions qualify for the H-1B vias that allow foreigners to work in the US for up to six years, in a potential blow to cheap Indian IT workers.

Reality: In March, the Chinese public security ministry announced plans to launch a pilot program to ease visa rules for foreign talent in a total of 20 free-trade zones, cities, and provinces. The new scheme allows anyone who has been employed in China for at least two years in a row to apply for a five-year work permit, compared with an annual renewal previously required.

In 2016, nearly 1,600 foreigners became Chinese permanent residents, a 163% increase from the previous year, according to official figures. In the first 10 years since China rolled out its green-card scheme in 2004, only 7,356 foreigners were granted permanent residency, out of an estimated 600,000 foreigners who live there. (By comparison, the US gives out around one million green cards each year.) Some foreigners have complained that the Chinese green card is of limited use.

On at least one issue, Xi and Trump can see eye to eye—the reluctance to take refugees (paywall). While other developing countries in the Middle East have borne the brunt of the outflow of refugees from Syria, by the end of August 2015, China had only taken nine refugees from Syria, who are waiting resettlement in another country. By the end of 2015, China hosted 301,052 refugees, according to the UN Refugee agency (pdf, p.57). Nearly all of them were accepted in 1979 during the Sino-Vietnamese war and are of Chinese origin.