To be tough with China on trade, Trump needs to be tough on the South China Sea

When US president Donald Trump hosts his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, in Florida this week, he promises to demand better trade terms with China. But there’s another issue of equal or arguably greater importance: the South China Sea.

When US president Donald Trump hosts his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, in Florida this week, he promises to demand better trade terms with China. But there’s another issue of equal or arguably greater importance: the South China Sea.

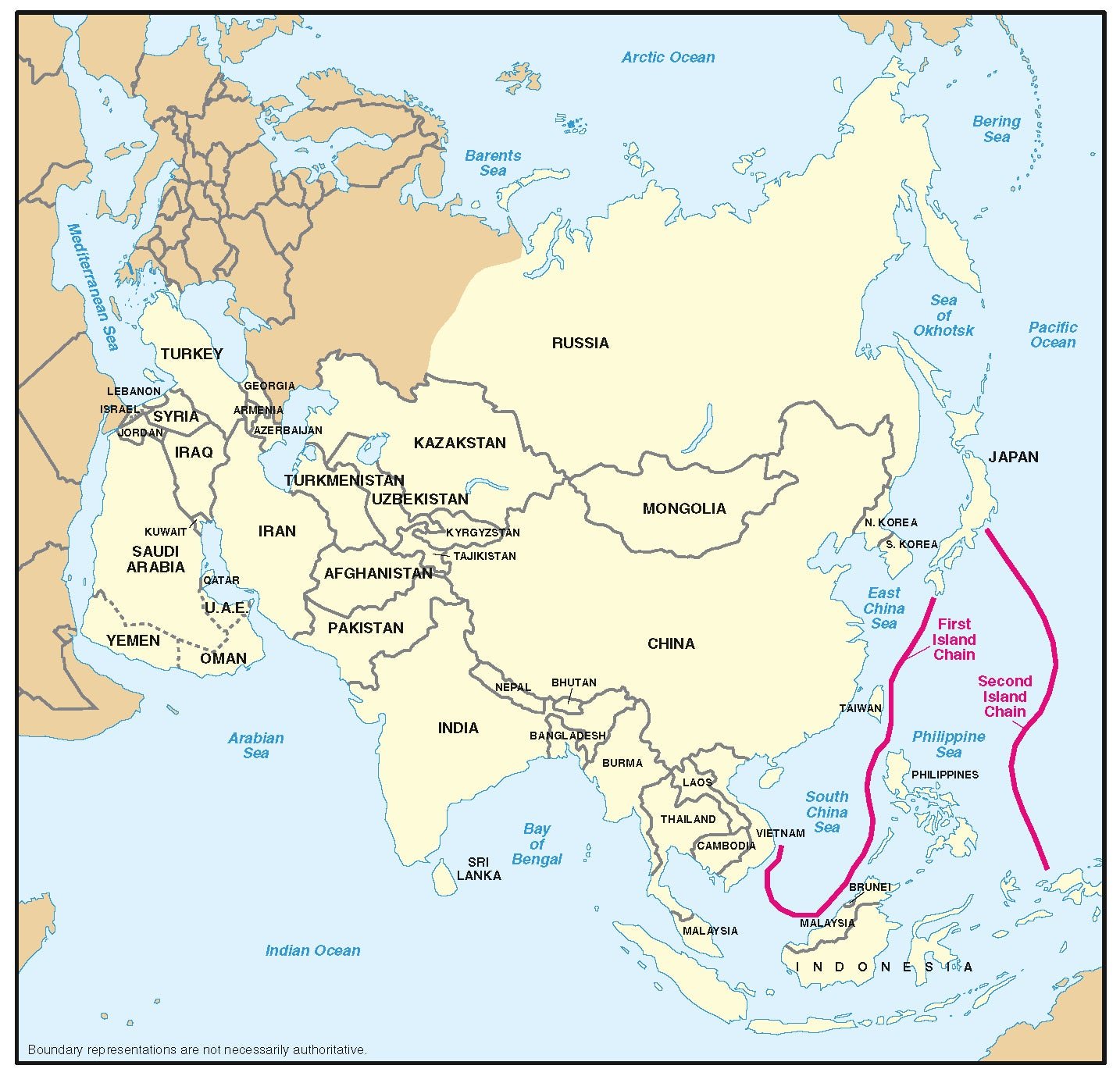

Each year, $5.3 trillion of global trade passes through the sea, including $1.2 trillion of US commerce. The US wants to defend the waterway as an open, unrestricted trade route. China wants to secure those waters (paywall), both for national defense and for projecting power in the region.

A deadly military incident or full-out conflict could well arise from these competing aims of the two great powers.

An international tribunal ruled last July that China’s sweeping claims to the sea had neither a legal nor historical basis, but Beijing quickly dismissed the ruling. In recent years it’s steadily built and fortified positions in the sea. Among them are artificial islands built atop reefs in the Spratly archipelago, and facilities installed on the Paracel islands.

The fear is that unless this is challenged, the sea will eventually become, in the words of a report last year by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, “virtually a Chinese lake” by 2030.

Trump’s attitude to China so far has followed the “speak loudly and carry a tiny stick” pattern of his foreign policy more generally. Last December he suggested the US might not stick to its long-held position that Taiwan is part of China. But then in February—after a phone call with Xi—he agreed to honor the “one China” policy. On trade, he has vowed to take drastic steps to reduce the trade deficit with China and force manufacturing jobs to return to the US, but when it comes to concrete actions, the moderates in his administration who favor milder changes are so far winning (paywall) over the hardliners.

Similarly, last December Trump warned of the “massive fortress” China is building in the sea, and his secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, said in his confirmation hearing that China should be denied access to the islands it has built. But Tillerson later clarified he meant the US should only make a move against China if its own forces are threatened. And in March, after visiting Beijing, he mirrored Xi’s diplomatic phrasings, saying the two nations should have a ”very positive relationship built on non-confrontation, no conflict, mutual respect, and always searching for win-win solutions.”

Given this, one has to wonder just how forceful Trump will be about the South China Sea while hosting Xi at Mar-a-Lago. Given the amount of US trade that passes through the sea, it should be at least as important to the US president as China’s tariff regime or investment rules.

China, remarkably, is still pushing the idea that its infrastructure in the South China Sea is “primarily for civilian purposes… even if there is a certain amount of defense equipment,” as Chinese premier Li Keqiang said last month while in Australia.

That notion has been barely credible for years. Beijing has established a clear pattern of using civilian elements to distract from the military nature of its developments, including visits to the islands by patriotic Chinese tourists. Japanese newswire Kyodo News reported last month that it acquired a copy of a People’s Liberation Army internal magazine issue containing an article describing the “policy of boosting the military influence in the area under the cloak of ‘civilian activities.’”

When China began building in the Spratly archipelago’s Mischief Reef in the mid-1990s, it reassured the nearby Philippines that it was merely making “fishermen’s shelters.” Today it’s hard to see the reef, once submerged at high tide, as anything other than a military installation—and a nearly complete one at that. The Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative wrote last month that the construction at Mischief and similar outposts “is wrapping up, with the naval, air, radar, and defensive facilities that AMTI has tracked for nearly two years largely complete.”

Having completed much of the physical work it needs to control the sea, China is now focused on bolstering rules and regulations to the same end. For instance, next month it plans to enforce a fishing moratorium in much of the sea—not just on its own fishermen, but on ones from other nations, too. And it’s considering a revision to its maritime “traffic safety” law that would require foreign submarines to stay surfaced and display their national flag while in the vast waters China deems its own.

It’s easy to imagine such rules accumulating over time, and China’s creeping control over the sea becoming “normal.” One obvious move Trump could order to counter that trend is a freedom-of-navigation operation at Mischief Reef, which, last July’s ruling determined, has no maritime territorial entitlements at all, and is technically not even a rock, much less an island.

So far, though, the new administration has seemed curiously hesitant about challenging China’s “massive fortress” in the sea. From Beijing’s perspective, if Trump continues with that approach during Xi’s Florida stay, so much the better for China. But it wouldn’t be good for the US.