The economic promise of post-apartheid South Africa is fading

Things look pretty bleak in South Africa right now. The political chaos of the present has made the economic future uncertain—and the lexicon of credit-ratings firms part of everyday conversations here.

Things look pretty bleak in South Africa right now. The political chaos of the present has made the economic future uncertain—and the lexicon of credit-ratings firms part of everyday conversations here.

Ever since president Jacob Zuma removed finance minister Nhlanhla Nene in December 2015, South Africans have feared the assessments of credit ratings firms like Standard & Poor’s watching the political upheaval. Nene’s replacement, David van Rooyen, lasted for less than week. His replacement, Pravin Gordhan, was finance minister before Nene took over in mid-2014. Gordhan’s second stint in the post lasted a bit more than a year—on March 31, Zuma fired him.

This was the last straw for the ratings agencies. On April 3, the downgrade everyone feared came to pass.

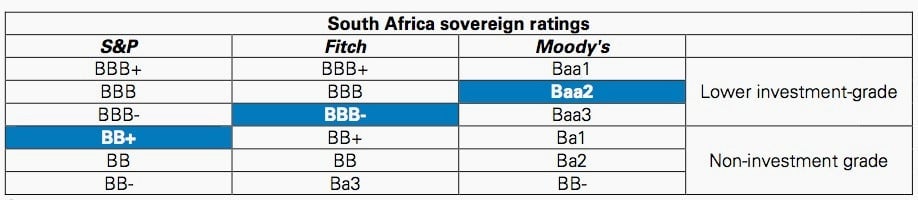

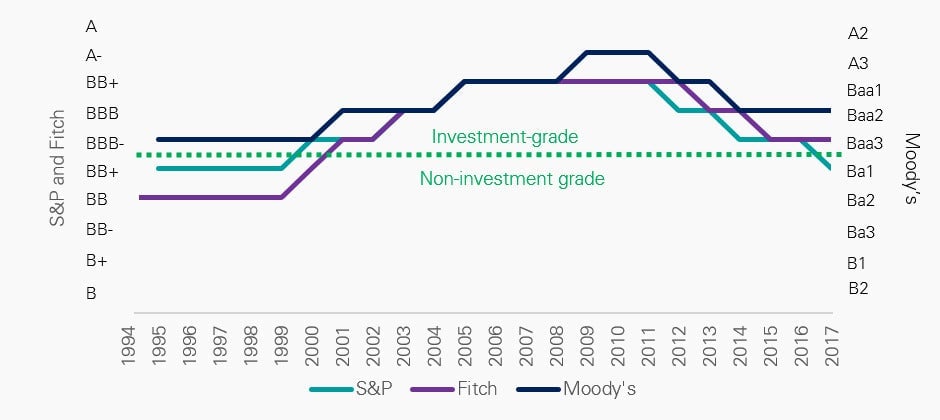

Standard and Poor’s acted swiftly to Gordhan’s dismissal, downgrading South Africa’s government bonds to a sub-investment-grade BB+, a “junk” rating. Moody’s suggested it, too, might be in a cutting mood; it placed the country’s BAA2 rating (two notches above junk) on review. Fitch has not yet commented; it rated South Africa at BBB- (one notch above junk) in 2016.

Ordinary South Africans generally are not au fait with the macro- and micro-economics that go into these ratings, but it’s the fact that they know even less about the reasons behind the cabinet reshuffling that has literally driven them to the streets. Civil society groups and opposition parties are planning to march this week, demanding that Zuma step down, because they blame him for the S&P downgrade.

What happens now?

“A ratings downgrade works a little like an interest rate hike,” Nolan Wapenaar of Anchor Capital said in a note. “The cost of debt and capital in a country will increase as a result of the downgrade.”

The simplest example of how this works is to imagine South Africa approaching a bank for a loan the way an individual may apply for a mortgage. If the lender thinks the borrower has become a riskier proposition, it makes the debt harder to get, by raising the interest rate or limiting the amount available to borrow.

“Like individuals approach a bank for a home loan to buy a house, governments source financing from international financial markets to fund key projects like new roads and power plants,” said ABSA Bank’s Chris Gilmour in a note to clients.

And indeed, the economic situation in South Africa could very well lead to higher rates for individuals. Using an online mortgage calculator from First National Bank, at the current prime interest rate of 10.5%, a 3 million rand ($218,700) three-bedroom home in one of Johannesburg’s northern suburbs will have a monthly repayment of 30,000 rand ($2,187) and require a gross income of 99,837 rand ($7,278) for a 20-year mortgage.

If that interest rate increases to 11.5%, the monthly repayment increases by 2,000 rand ($145.80). These may not seem like large amounts, but to a small, stretched, and already indebted middle class they are the difference between manageable and unaffordable, especially if taxes are raised. With less money to spend, this has a knock-on effect on the informal and wage economies.

For now, the banks are more likely to feel the pinch than their customers. Bank stocks tumbled at the news that Gordhan was booted from his post, and have continued to slide after the resulting downgrade. The index of South African banks has lost 8% since March 31, according to Bloomberg.

“Suddenly, their capital has become more expensive, which leads to lower profits and lower trading on the stock market,” explains KPMG economist Christie Viljoen. Ordinary South Africans will experience the effects of the downgrade in the quarters to come, as the price of fuel and imported goods begin to increase. The South African Reserve Bank will not immediately raise interest rates, but if inflation continues to rise, interest rates will have to follow suit, says Viljoen.

Has this happened before?

South Africa has spent time in “junk” territory before. When the rand was in crisis mode in 1998 and 2001, interest rates were set at levels that would shock South Africans today. In October 1998, the prime lending rate was 24.5%, more than double the current rate.

In 1998 and 2001, the factors influencing the depreciation were far less politically fraught. Despite the gains made since 1994, the rand depreciated significantly from May to September in 1998 and from October to December in 2001.

The crisis caused less public outcry and may have been due to a case of “exchange rate overshooting,” and to a lesser extent social factors like the AIDS-pandemic and the slow privatization of state-owned companies, according to economists (pdf) Ashok Bhundia and Lucca Ricci. Overshooting is a model economists use to explain the volatility of exchange rates in reaction to changes in fiscal or monetary policy. In the case of South Africa in 2001, that led to an acceleration in money growth. Today, it could be used to explain the currency’s sensitivity to political infighting.

At the time, under Thabo Mbeki, who was deputy president during the first crisis and president during the second, South Africa’s sound fiscal policy was credited for staving off the long-term effects of the currency crisis. The central bank also learned its lesson: its intervention in the first crisis hindered a recovery, leading to a policy of non-interference that is still in place today.

What could happen?

As much as an investment-grade rating had become a matter of national pride, the truth is the country had only recently enjoyed that status, since 2000. To its advantage, most of South Africa’s public debt is held domestically: 88% marketable debt and 3% non-marketable debt versus the 9% of foreign-held debt, according to a report by KPMG.

South Africa now finds itself among countries like Portugal, Cyprus, and the Bahamas—not the worst company to be in. As the new finance minister Malusi Gigaba said optimistically, it could be an opportunity to “ignite growth.”

“I don’t think there should be panic about the downgrade, but what it symbolizes,” Viljoen tells Quartz. “It symbolizes political risk and uncertainty and the impact that’ll have on the economy.”

Therein lies the cause of the hysteria. Zuma is seen to have acted unilaterally to change a crucial portfolio in his cabinet, giving South Africa its fourth finance minister in 16 months. The business community and international investors viewed Gordhan as a prudent, steady driver of South Africa’s economy. Gordhan was especially favored for his single-minded determination to reduce South Africa’s deficit.

Moody’s and S&P directly attributed their recent actions to Zuma’s midnight reshuffling. The move implies a lack of clear fiscal policy needed to ensure South Africa’s already slow growth doesn’t grind to a halt. The Banking Association of South Africa has labeled Zuma’s actions and the ensuing downgrade as a crisis “leading to a steep erosion of already poor levels of investor confidence.”

Downgrade decisions are not made lightly, and it will take years to convince ratings companies to change their minds, says Viljoen. But that would require rehabilitation, and even before that, the country’s policy makers would have to admit that there is in fact a problem.

Zuma, meanwhile, has thus far defended his decision to fire Gordhan. He and his supporters promise that the reshuffled cabinet will bring about “radical economic transformation”—a policy direction that is often repeated but rarely explained, only adding to the concerns over policy confusion. Unlike during the crises of 1998 and 2001, South Africa does not seem to have a clear strategy to dig itself out of a hole.

“The difference is that we were then emerging from a very, very bad period of fiscal and economic policies,” says Viljoen, referring to the apartheid government’s policies. “What we’re doing now is that we’ve gone backwards and we’re deteriorating.”