Apple’s new file system: Who cares?

Who on Earth regards a computer’s file system as anything more than a bland office worker? But if we dig a little deeper there’s a story to be told, one that concerns the future of Apple’s widening array of operating system versions and hardware devices.

Who on Earth regards a computer’s file system as anything more than a bland office worker? But if we dig a little deeper there’s a story to be told, one that concerns the future of Apple’s widening array of operating system versions and hardware devices.

While the file system is a computer’s most vital organ, to the normal consumer it’s a bore, and even from knowledgable critics it rarely draws praise. But let’s not ignore the all-important whats and whos: What’s the job to be done (JTBD), and for whom?

Today, we’ll consider three constituencies who have intertwined interests in Apple’s new APFS file system, recently deployed to all iOS, Watch, and TV devices:

- Users—a.k.a. paying customers, the only real source of money;

- Application developers who broaden the appeal of Apple devices;

- Apple itself.

For users, the JTBD story appears to be simple: “I want to store, catalog, and retrieve my files, whether they’re work documents, travel pictures, ebooks, tax forms…” A subset of more sophisticated users will understand and appreciate the impact of APFS’ atomicity, nanosecond data resolution, and file-level multi-key encryption, but mention these features to a normal user and you’ll draw a blank stare.

Simply put, the rest of us don’t care… except that we do; we just don’t know it. APFS’ esoteric-sounding new features mean encryption will be easier to use, disk space will be better utilized, and backups will be more reliable, to name but a few improvements. Overall, iPhone and iPad (and Apple Watch and Apple TV) have become “future-proof” now that they’ve shed the 30-year-old HFS+. You probably didn’t even know it happened. That’s high praise for a vital organ transplant.

As a personal anecdote, I didn’t pay attention when my spouse’s MacBook Air repeatedly failed to backup on the family’s Airport Time Capsule. I trusted the MacBook Air, we never had trouble with any of our Mac laptops, and thought I could get around to hunting down the Time Capsule bug later. When I finally did, I discovered there was nothing wrong with our backup device. The problem was with corrupted files on the laptop’s Solid State Drive (SSD). They were so damaged that Apple’s Disk Utility refused to repair the SSD. Various attempts to find a workaround landed me in the arms of a disk cloner called Super Duper. I use it religiously before trips so we carry around bootable copies of our drives. That way, in an emergency, I could ask someone to let me boot the backup drive on their Mac and function without disturbing their system. Log off, eject the backup drive, and the host system is back to normal, untouched.

As I tried to back up the sick SSD, the disk cloner balked and stopped, always at the same place. More poking around detected corrupted picture files. So, I spent the next 48 hours hunting for and deleting such bad files, attempting cloning operations and going back to the hunt until all culprits were gone. (There might have been smarter ways to cure the problem. Feel free to have fun at this klutz’s expense.)

This SSD degradation is sometimes known as “bit rot,” something a more modern file system such as APFS might have detected with a clearly labeled error message, if not autocorrected. This is what modern file systems such as Btrfs and ZFS are supposed to do—but they’re not widely deployed on PCs and other consumer devices.

For developers, things aren’t so transparent. Apple has issued a new set of Application Programming Interfaces (API)—specifications that allow third-party app developers to take advantage of the file system’s new features. This is mostly but not entirely good news. New application frameworks come with fresh bugs in the code and mistakes in the documentation, but the technical benefits—better file transaction integrity, more flexible storage management, native encryption (as opposed to the bolted-on File Vault)—aren’t just compelling, they’re compulsory. As Apple’s Developer Documentation explains in succinct, plain English, age doesn’t become a file system [as always, edits and emphasis mine]:

HFS+ and its predecessor HFS are more than 30 years old. These file systems were developed in an era of floppy disks and spinning hard drives, when file sizes were calculated in kilobytes or megabytes.

Today, people commonly store hundreds of gigabytes and access millions of files on high-speed, low-latency flash drives. People carry their data with them, and they demand that sensitive information be secure.

(Also see Backblaze’s eminently readable assessment of APFS’ technical details.)

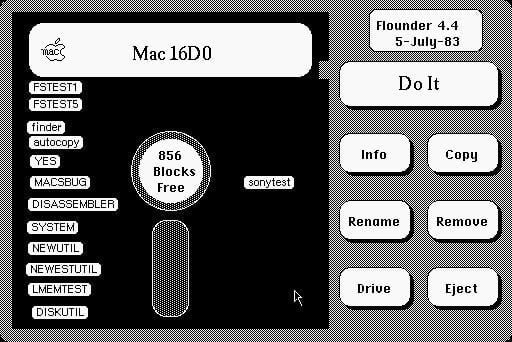

Very old-timers will remember the pre-Mac File system called The Flounder:

(I recall an even cruder version that showed files being thrown around the surface of a circular floppy disk, but can’t find it on the internet.)

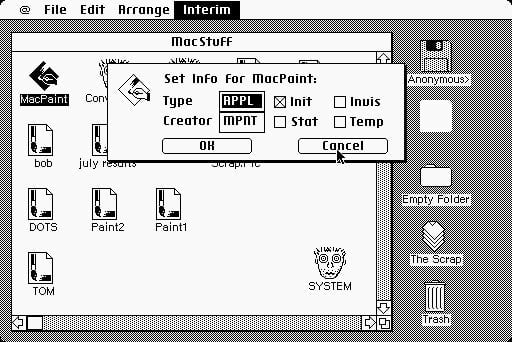

This gave way to the 1984 Mac Finder:

Applications and files were just there, no hierarchy, no folders.

The Hierarchical File System (HFS) was quickly introduced in 1985 and started its long march towards what we know today. As you can imagine, the ancient HFS contains layers upon layers of patches, extensions, and dried glue. (One of APFS’ architects, Dominic Giampaolo, had previously designed and built the BeOS file system using, as one of his guides, his knowledge of HFS’ shortcomings.)

Of note, the company designed APFS to support iOS where the file system is still largely out of users’ reach. Files and folders are available in the iCloud Drive on an iPhone or iPad, but we can’t create folders there, they have to be created on a Mac, or we can add files to fixed system categories:

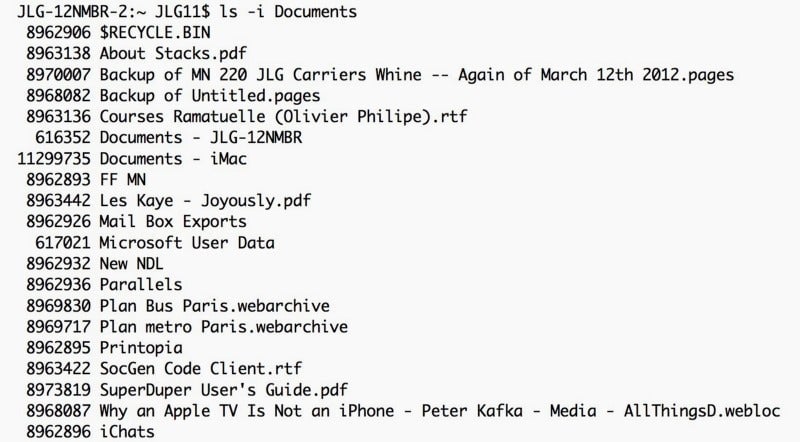

In other words, there isn’t yet an iOS equivalent to the Mac’s Finder, our macOS interface to the file system. By “our” I mean most of us. Savvy Mac users know how to wield a Terminal window where they can manipulate everything in the file system—or even destroy everything on the disk:

For Apple, APFS is an opportunity to become young again, without losing the memories and artifacts of one’s complicated past. Apple’s closed systems, so often criticized, make the transition easier, safer. There will be bugs, but with this fresh start in a closed system, they’ll be much easier to identify and fix, as opposed to dealing with “creative” hardware variations decided in the purchasing office of some distant OS licensee. (A director of the largest PC OS licensing company once told me they spent more money on driver development and fixes than on OS code proper.)

It’ll be interesting to see what happens when APFS comes to macOS and its complicated burden of past sins. In the meantime, the “iOS First” release once again speaks to Apple’s priorities, to its vision of its future. As for last week’s “interesting” discussion of future Mac Pros and iMacs, I’ll wait for Apple’s quarterly numbers to be released in three weeks, on May 2nd.