Bernanke may have one more Fed revolution left up his sleeve

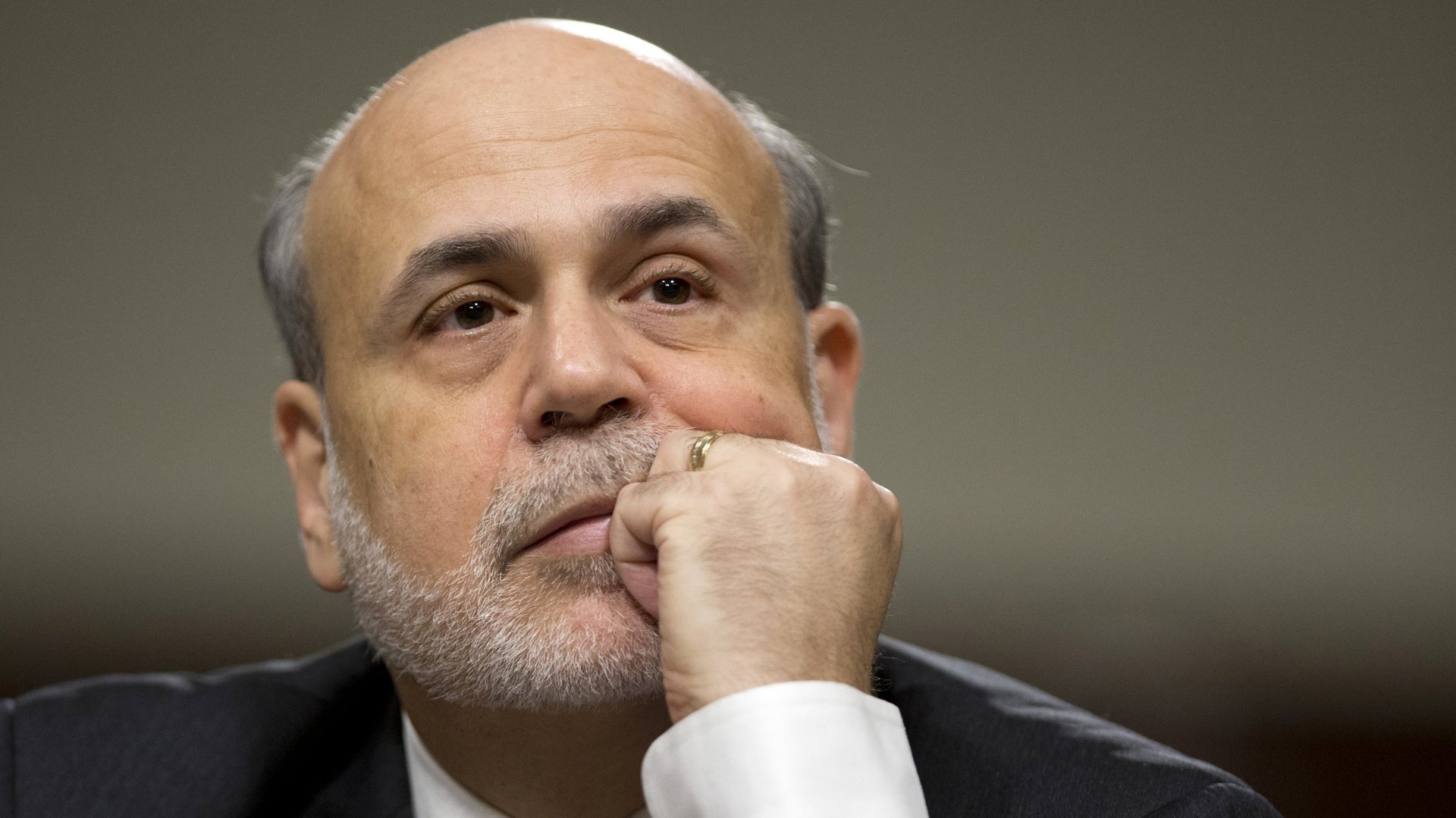

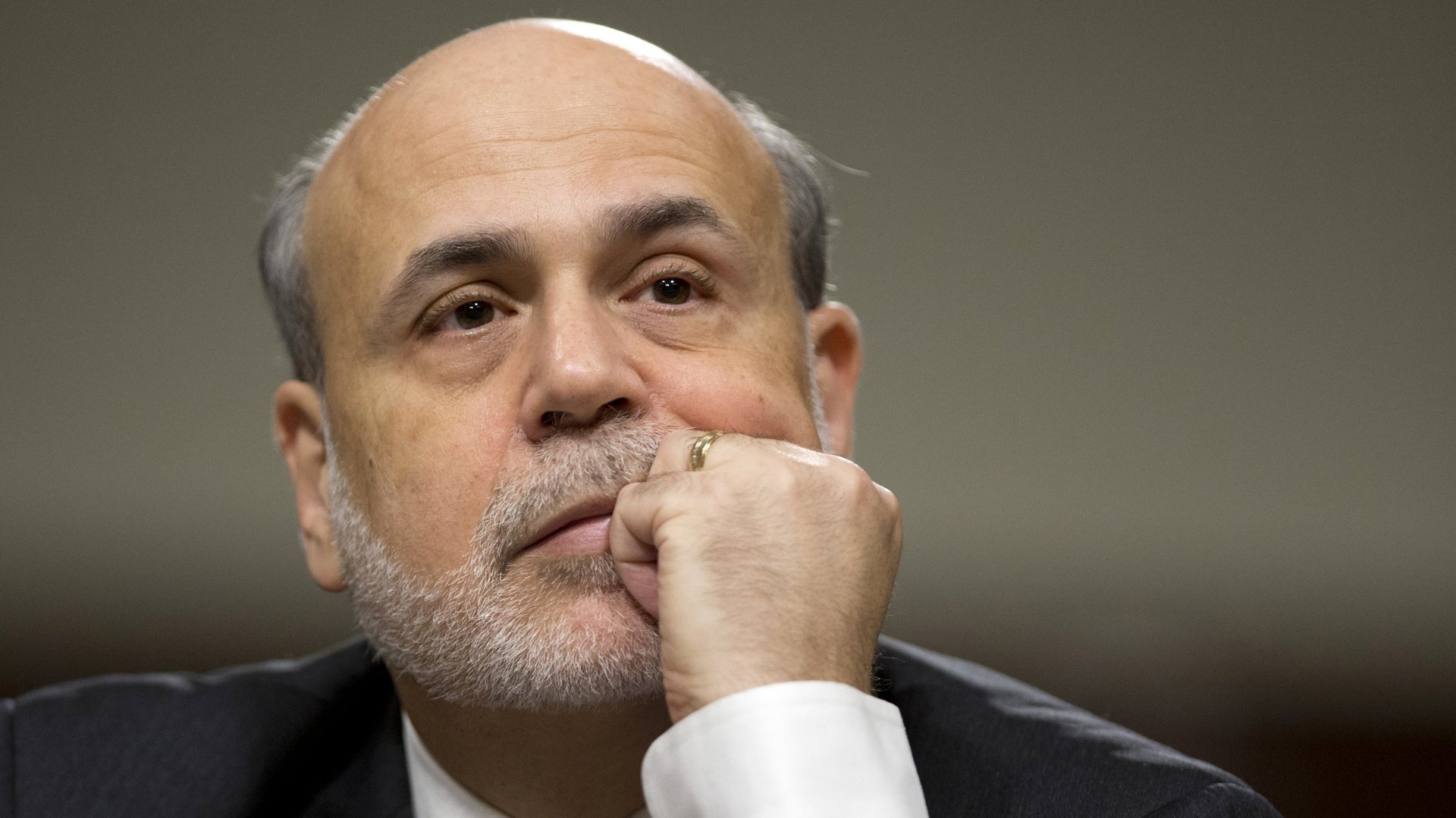

President Obama all but made it official this week, saying that Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke has stayed at the Federal Reserve “a lot longer than he wanted or he was supposed to.” Many had already assumed that Bernanke would step down when his term ends in January 2014. But the president’s comments cement the idea that the era of the Bernanke Fed is coming to an end.

President Obama all but made it official this week, saying that Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke has stayed at the Federal Reserve “a lot longer than he wanted or he was supposed to.” Many had already assumed that Bernanke would step down when his term ends in January 2014. But the president’s comments cement the idea that the era of the Bernanke Fed is coming to an end.

And what a Fed it’s been! Under Bernanke, the Fed broke ground on multiple fronts. As a firefighter, it pioneered an alphabet soup of programs during the worst of the financial crisis to keep the credit markets from collapsing completely.

The Fed also added an inflation target, acquired the power to pay interest on excess bank reserves, expanded the breadth of official published forecasts and added official press conferences after monetary policy decisions. Any one of those would have been considered a marquee accomplishment in annals of the US central bank.

With its main policy rates parked at zero, the Bernanke Fed has been forced to embarked on a range of extraordinary programs known colloquially as QE1, QE2, Operation Twist and QE3. While the details vary, the general idea is to buy financial assets—mostly Treasury bonds and government-guaranteed packages of mortgages—as a way to force more money into the economy.

Of course, Bernanke didn’t set out to be such a trailblazer. He was forced into it by the biggest financial panic in modern memory and the deepest recession since the Great Depression.

And now, with the US economy looking hale, the biggest challenge the Fed faces is slowly removing the support that kept the US economy upright in recent years, without startling the markets. And that’s why we think Bernanke may have one more major innovation to do before he trots out the door.

RIP Fed Funds Rate?

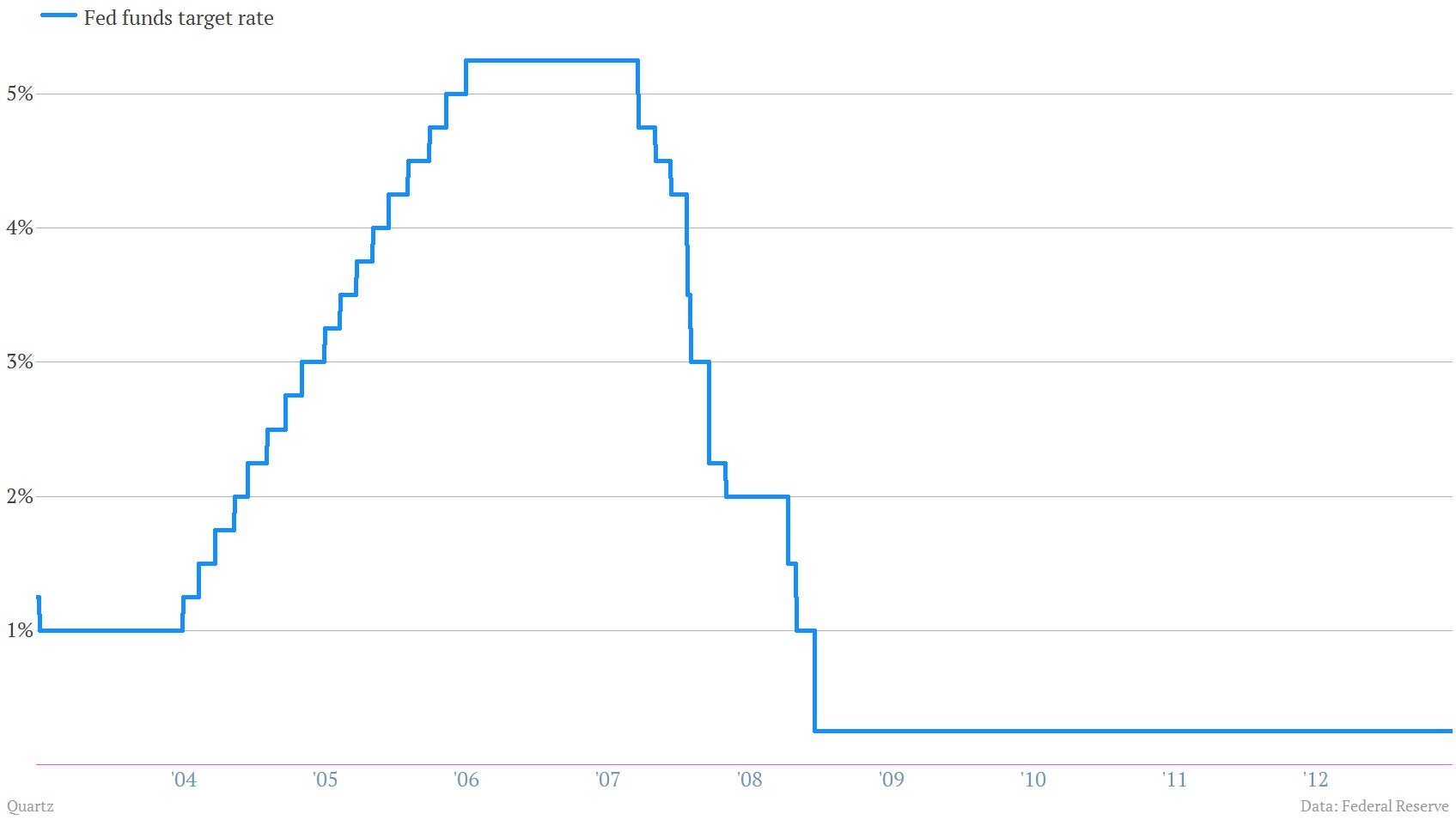

Remember the federal funds rate? Don’t feel bad if you don’t. It hasn’t really mattered since the Federal Reserve pushed it down to almost zero in January 2009, during some of the worst moments of the recession. It’s been there ever since. This is what it looks like when the Federal Reserve is flooring the gas pedal of the country’s economic engine.

Now as we said above, the Fed is increasingly signaling that it’s going to be trying to take its supportive hand off of the economy’s bike seat over the next few months. That would be an important shift in monetary policy—but also a confusing one. In the past, when the Fed wanted to shift policy all it had to do was move the federal funds rate. But the current situation is different.

Think about Ben Bernanke’s hand on that bike seat of a wobbly and timorous US economy. It’s the economy’s first time back on the bike after a nasty spill. Bernanke is not ready to take his hand off completely. And it’s not as if the bike rider is overly confident and about to dart ahead into traffic, which would require Mr. Bernanke to restrain it. No, the Fed is going to start to ease up on its grip, allowing the little guy to support a bit more of his own weight.

Now, we don’t think the Federal Reserve is about to add this little heartwarming vignette into the FOMC monetary statement. But how the heck do you communicate something this delicate? Well, it turns out nobody really knows—perhaps not even members of the Fed’s monetary policy committee. Here’s an interesting excerpt from the minutes of the committee’s last meeting.

Several participants raised the possibility that the federal funds rate might not, in the future, be the best indicator of the general level of short-term interest rates, and supported further staff study of potential alternative approaches to implementing monetary policy in the longer term and of possible new tools to improve control over short-term interest rates.

It would be hard to overstate how revolutionary a permanent move away from focusing on the funds rate would be. (The federal funds rate is the rate banks charge each other for overnight loans.)

Others have tried it, including Paul Volcker, who in 1979 announced that the Fed would be focused on the money supply rather than the funds rate, an episode that became known in Fed lore as the “monetarist experiment.” But it didn’t last and since the early 1980s the funds rate has been at the heart of what the Fed does—especially after July 1995, when the Fed started explicitly spelling out the target for the rate in its monetary policy statements.

There’s no indication that the Fed will make such a move. It might happen after the end of Bernanke’s term in 2014. But if anyone would be willing to undertake such a epoch-making alteration to Fed policy it would be Bernanke. After all, he’s had plenty of practice.