A simple system helped me to stop obsessing over work and start prioritizing my family

In my twenties, I was a lean, mean productivity machine. I created an alternative shorthand keyboard on my Blackberry to reduce my keystrokes by 80%. I devoured audiobook biographies of Steve Jobs and other great leaders by listening to them at 2.5x normal speed. I even optimized my workouts by cramming the most efficient exercise (burpees) into the most efficient form of interval training (the four-minute Tabata). My life was a productivity masterpiece, but with one catch: Like a game of Jenga in the late innings, the slightest addition could cause the entire thing to collapse.

In my twenties, I was a lean, mean productivity machine. I created an alternative shorthand keyboard on my Blackberry to reduce my keystrokes by 80%. I devoured audiobook biographies of Steve Jobs and other great leaders by listening to them at 2.5x normal speed. I even optimized my workouts by cramming the most efficient exercise (burpees) into the most efficient form of interval training (the four-minute Tabata). My life was a productivity masterpiece, but with one catch: Like a game of Jenga in the late innings, the slightest addition could cause the entire thing to collapse.

So three years ago, when my wife Lisa showed me the “plus” sign on the pregnancy test, I was elated. I had looked forward to this day for a very long time. I was going to be a dad. But in the back of my mind, I was also terrified. My fierce work ethic was a big part of my identity. Would fatherhood make it harder for me to keep up with all those young, single people at my job, with their boundless energy? Would my ambition atrophy?

It’s a fear that plenty of new parents have grappled with. But research suggests that parenthood doesn’t have to take a toll on careers. A 2014 paper from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, for example, surveyed the publication records of 10,000 economists in academia. It found that, overall, mothers and fathers were even more productive than men and women without children.

This isn’t meant to discount the challenges of parenthood, or the effects of sexism and traditional gender roles on career advancement. But as men and women evolve away from the traditional division of labor at work and at home, it seems clear that the quality of our work doesn’t have to suffer when we expand our families. Rather, the way we work is what has to change. I knew I wanted to be a strong presence in my daughter’s life. And that meant it was time to reevaluate my priorities.

The Eisenhower Box

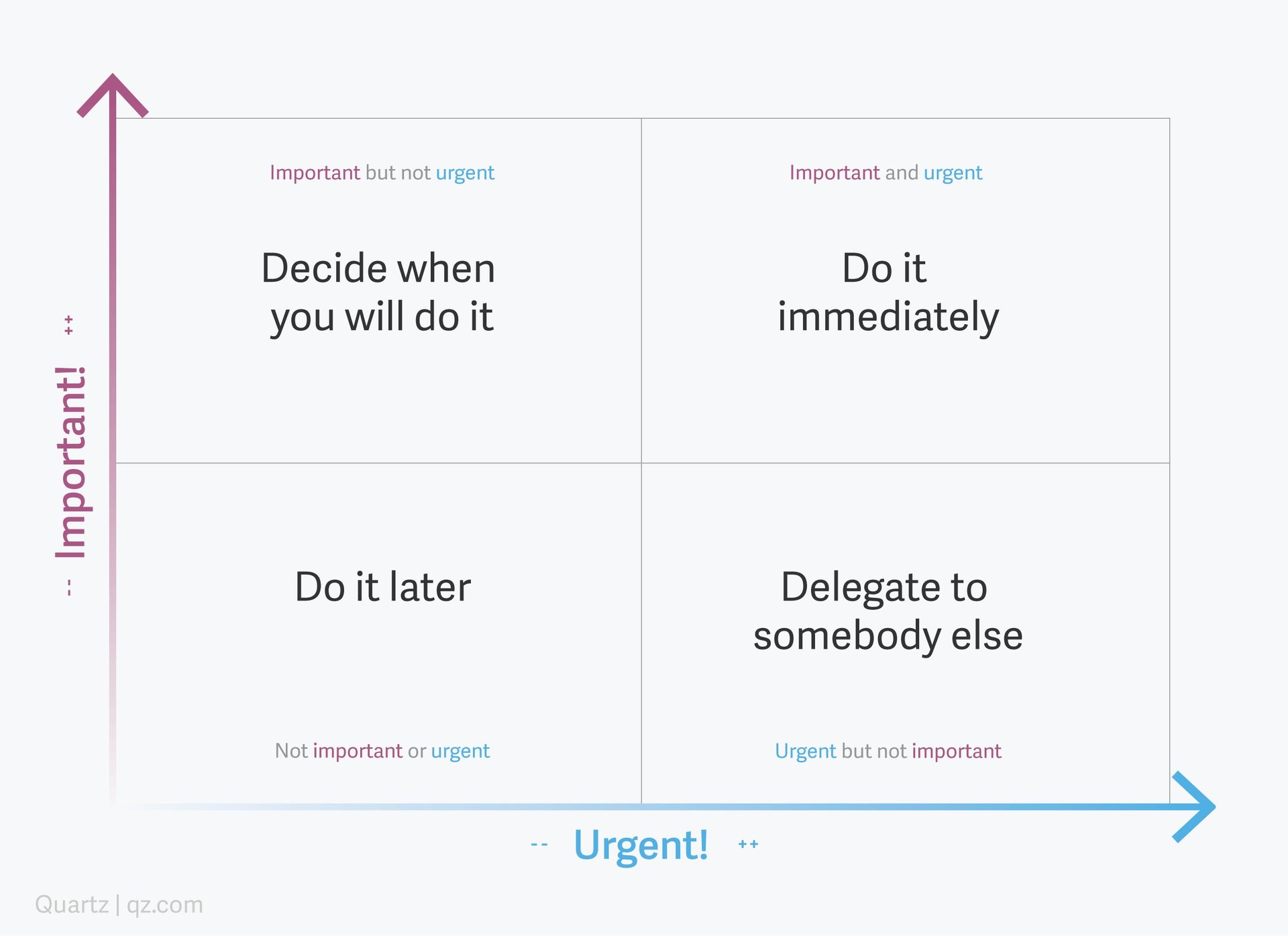

In my quest to achieve a better work-life balance, I turned to a framework called the Eisenhower Box. The system named after the 34th president of the United States, who famously said, “I have two kinds of problems, the urgent and the important. The urgent are not important, and the important are never urgent.” Eisenhower understood that it is easy for long-term priorities—in my case, nurturing loving relationships with my wife and daughter—to be overshadowed by daily, deadline-driven, but ultimately insignificant tasks. The Eisenhower Box is a tool meant to help people better manage their time and priorities, so that the important stuff doesn’t get lost in the shuffle.

To create an Eisenhower Box, you draw a matrix with four quadrants. The horizontal axis represents “urgency”; the vertical axis represents “importance.” This matrix leaves you with the following four quadrants, as explained in The Decision Book: 50 Models for Strategic Thinking.

When I first discovered this framework, I hadn’t really considered the distinction between importance and urgency. Instead I equated the two—which meant that I gave priority to the time-sensitive tasks that made me feel a surge of accomplishment (and dopamine) upon completion. I assumed that the more things I checked off my to-do list, the better I’d feel. As economists Ted O’Donoghue and Matthew Rabin write, immediate gratification, in all its forms, ”can lead a person to behave in ways different from how she would like to behave from a long-run perspective.”

Parenthood is the anti-thesis of instant gratification; its rewards are cumulative, and more long-term. So the Eisenhower Box helped me figure out how to triage the things I wanted to do in a given period of time, with the goal of having family life—not work—be the centerpiece of my days.

At first, I would think of everything I planned to do in a given week and plot it all on the matrix, so that I could do a better job of prioritizing. I was struck by how easily it helped me focus on longer-term goals. Soon it became a lot easier for me to mentally organize tasks. Here’s how the system works.

Important and urgent

This is the stuff I need to deal with ASAP—tasks or events that have a fixed deadline, with serious consequences if they lapse. Recurring events like paying rent or bills might be on this list or one-offs like evaluating preschools or enrolling in a new health-care plan. Because the cost of missing the deadlines is high, tasks that are in this category need to be prioritized. My day or week might need to be organized around meeting them.

This is also the category of tasks where efficiency and productivity really do matter; I want to make sure I get these things done, and in a timely manner. A few scientific-backed productivity tricks I rely upon: doing work in batches to avoid the pitfalls of multitasking, and managing my energy (with bedtimes and exercise rituals) instead of trying to manage my time.

Not important and not urgent

This was a key part of my new life as a dad: Realistically, I didn’t have time to do everything I used to do, so I needed to figure out what I could drop. Filling out this square showed me a lot of activities in a given day that I could pretty painlessly cut out: watching sports and playing fantasy football, along with my daily dose of TMZ and Page Six, and Facebook. Most time-pressed people have similarly unimportant activities they can give up.

Tiffany Dufu, a women’s advocate and author of the book Drop the Ball, also recommends that working parents reexamine the things they feel like they’re supposed to do—including nice but ultimately optional tasks like color-coding the filing cabinet or ironing bedsheets. When you give up on such tasks, she says, “the world does not fall apart.”

I also realized that I could stop spending time with people who were draining me of energy. Before fatherhood, I might meet with friends and colleagues out of a sense of obligation, even if the encounter left me feeling worse. Having a young child at home made dropping those kinds of meetings a no-brainer.

Not important and urgent

This category turned out to include most of my anxiety-producing tasks. The incessant demands of our “always on” connectivity fall into this quadrant—messages from colleagues and acquaintances asking to schedule or sending links to a video to watch or an article to read.

How should one cope with all these requests? The Eisenhower matrix helped clarify one thing: Just because a request was important to the sender didn’t mean it was necessarily important to me. One of my biggest fatherhood learnings was that the repercussions for failing to respond to a message in this category are low, and there’s typically not a real deadline for dealing with it. Once you let go of holding yourself to unreasonable response times and antiquated concepts like Inbox Zero, you liberate yourself to focus on the important stuff.

This attitude has been touted by Jocelyn Glei, author of Unsubscribe: How to Kill Email Anxiety, Avoid Distraction, and Get Work Done. She argues that the rule of reciprocity makes us feel obligated to respond to personal messages, even when the volume of those messages means it’s simply unrealistic to do so. Instead, she recommends thinking of email as snail mail: “If you got 200+ letters a day, you would never think it was realistic to respond to all of them. Why should email be any different? Your time is limited, and you can only respond to so much.”

Filling out this quadrant also helped me recognize how much FOMO, or fear of missing out, can wind up driving the way I spend my time. Before my daughter was born, I was always heading off to professional events—breakfasts, dinners, happy hours. Afterward, it became imperative for me to set clear boundaries to protect family time.

My schedule is demanding, but it’s also very flexible. So I decided to follow the lead of Amazon chief Jeff Bezos, who famously makes sure to enjoy a leisurely breakfast with his wife, so that she can get the “best hours of [his] day.” Like Bezos, I opted to block out family time first, ensuring that everything else had to be scheduled around it.

Mornings are a time when the three of us sit in the living room and chat about the past night’s dreams (and day’s plans). Once that’s done, the mad rush of preparing for school ensues. This time came at the expense of my morning breakfast networking meeting, a longstanding tradition of mine.

Meanwhile, in the evenings, I’m usually spearheading the bath-story-bed routines, so I cap the number of nights out at two a week—which creates a high bar for events. This policy has cost me a Rihanna concert, some Nets games, and invites to a few swanky NYC restaurants. I won’t lie—some of this stuff has been hard to give up. But as my daughter’s grown up, she’s identified me as the “gatekeeper” for this part of her routine. Our mutual anticipation of which book we’ll read, or what songs we’ll sing, builds throughout the day.

Important, but not urgent

This last quadrant is the one that’s most important to me—and the one that’s most difficult to do right. For business leaders, important but not urgent tasks include working on strategic goals, long-term planning, investment in talent, and building a brand. These tasks usually don’t have deadlines; in fact, calling them tasks oversimplifies their nature. And they have limited repercussions for inaction. It’s easy to kick the can down the road.

In my personal life, what falls into this category is the simple act of spending time—and staying present—with my daughter. Particularly with babies under 18 months or so, it can be tempting to multitask their early childhood away. After all, you’ve got a cute, barely mobile blob, safe in her bouncy chair, with little risk of harming herself. You’re sitting right next to her; she’s just staring at her mobile. What’s the harm in firing off a couple emails on the iPhone?

Well, it turns out that paying attention—even when nothing seems to be going on—can make a big difference. A 2016 study, published in Current Biology, found that infants will look at a given object for longer if the parents are looking at the object too, which can influence the development of their attention spans down the line. And a 2002 study published in the journal PNAS found that, even from birth, babies prefer mutual eye contact, which the authors suggest is “arguably the major foundation for the later development of social skills.”

I still find it very hard to be fully present with my daughter as much as I would like. With a supercomputer in my pocket, there’s always something “productive” I could or should be doing. The work of Google’s former “Jolly Good Fellow” Chade Meng-Tang has really helped me here—his notion that if you pay attention, there’s joy everywhere around you. He refers to this abundance as “thin slices of joy.”

That simple reframing has helped me realize that a given morning with my daughter offers any number of thin slices of joy: a dimple when she smiles, her delight when she figures out that the oven light switch (because it’s at her eye level) produces endless entertainment, a guttural laugh that comes out of nowhere. Those moments are actually important, but not urgent, so it’s tempting to let them slip away in the name of productivity.

Most importantly, there’s my amazing wife. Parenting books and advice tend to focus on the new addition to the family. They don’t often talk about how hard it is to maintain a connection with your better half.

I was naive and thought that the shared joy of raising a child would bring a couple together. But while a child brings many good things to a marriage, it also introduces an entirely new set of challenges—particularly stress and exhaustion.

But there are also steps that couples can take to protect their marriage against stressors. I’ve recently found myself learning from the work of the psychology professor John Gottman on marital stability, particular one of his 7 Principles for Making Marriage Work: “Enhancing Love Maps.” Gottman explains that marriage bonds are strongest when both spouses have a mutual understanding of each other’s “worries, hopes, and goals in life.”

I’ll admit that prior to having a child, I couldn’t always elucidate those. Post-fatherhood, it’s become even more challenging. So I make sure to block out time when my wife and I can have one-on-one talks, centered around one simple question: “How are you feeling about everything?” On one recent drive, “everything” turned out to encompass the anxieties around having a second child, challenges balancing home-life and career, and my wife’s incessant feeling that she’s never doing enough. It always amazes me how that one question can open up hours of intense conversation.

A new way of life

I’m now three years into fatherhood, and damn, am I having a good time with our little girl. It’s true that I now have less time and energy for work, reading, and exercise. That isn’t going to change anytime soon—especially with a second one on the way.

But having a kid hasn’t had a negative effect on my work. In fact, it turned out that not only was my little one a garrulous bundle of joy, she also imposed constraints that had unexpected—but ultimately positive—consequences for my work-life balance. Before my daughter was born, I’d tried to quantify success in most areas of life: the number of books read, blog posts written, or meetings scheduled.

Having my daughter changed the way I think about spending my time. I still care about productivity when it comes to work. But when I wake up in the morning, I no longer think of the whole day ahead as a series of boxes waiting to be checked off. Instead, I focus my productivity on the urgent things so that I can get to the open spaces—the joyous stretches of time when I’m just with my family, not trying to achieve anything at all.

This Quartz story originally appeared on qz.com on April 18, 2017.