Uber is shutting down one of its restaurant delivery services

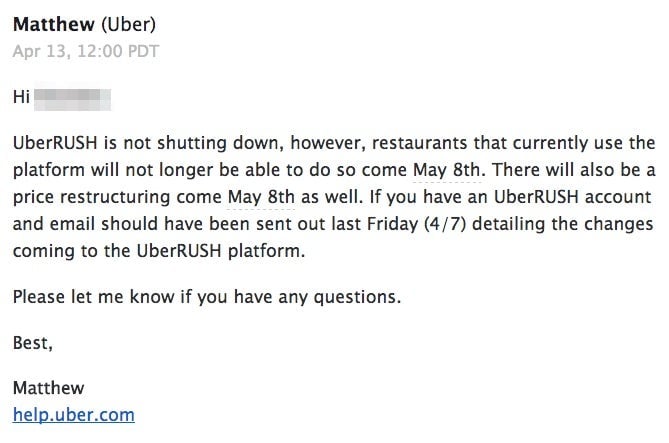

Uber plans to shut down UberRush, its backend logistics and courier service, for restaurants on May 8, Quartz has learned.

Uber plans to shut down UberRush, its backend logistics and courier service, for restaurants on May 8, Quartz has learned.

Uber introduced Rush in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco in October 2015. It was an important addition to Uber’s portfolio, an attempt to make good on CEO Travis Kalanick’s promise that ”if we can get you a car in five minutes, we can get you anything in five minutes.”

The company echoed that language at launch, saying Rush would use the technology behind on-demand rides to “get customers pretty much anything in minutes.” Early businesses to sign up for Rush included Blockheads, a New York burrito chain; ChowNow, a Grubhub competitor; Delivery.com, an online ordering platform for anything from food to dry cleaning; and BloomNet, a flower delivery service.

But a year and a half down the road, Rush’s future looks uncertain. Uber last week emailed Rush clients informing them that as of May 8, restaurants will no longer be able to use the platform. The company is encouraging restaurants to switchover to UberEats, its designated food delivery service. Restaurant deliveries have historically made up the majority of orders on Rush, two former employees familiar with Uber’s operations told Quartz.

Uber also plans to restructure pricing on Rush beginning in May. Currently, Rush deliveries cost $6 for the first mile and $3 for each additional mile in San Francisco; $6.30 for the first mile and $1.80 for each additional mile in Chicago; and $5.50 for the first mile plus $2.50 per extra mile in New York, according to the company’s website.

“We built UberEats to specifically meet the needs and support the growth of our individual restaurant partners,” a spokeswoman for Uber said in an email. “Moving forward, we will focus UberRush on powering backend delivery logistics for merchants and enterprises such as grocery stores and florists.”

Uber has struggled to balance the needs of its various on-demand platforms—rides, UberRush, and UberEats—which at times rely on the same network of drivers and couriers. Uber hires these workers as independent contractors to avoid paying them benefits or a guaranteed minimum wage, but because of that it can’t tell drivers when or where to work. The company has also had a hard time retaining workers, with only about 50% remaining after one year.

As Uber invested more in Rush and Eats, the delivery services ate into the labor supply for Uber’s core rides business, one of the former employees told Quartz. “We got into a situation where dinner rush would mean a lot of people were taking food deliveries, but then they weren’t driving for UberX, so it was causing surge pricing,” the person said. “We were attacking our own business.”

Uber said it is actively working to expand its pool of delivery people for Rush and Eats. Workers go through a separate signup process to deliver for Uber than to drive (though they can sign up to do both). Delivery is open to people ages 18 and older and doesn’t necessarily require a car. Drivers must be at least 21 years old and, of course, need a car.

Uber last year intensified its focus on UberEats, a service that competes with food delivery startups such as Postmates and DoorDash. The company poured money into UberEats, with a focus on expanding the platform’s reach and ordering options. Approximately 25,500 restaurants were registered on UberEats as of March, concentrated in big cities, according to data from financial analysis firm Thinknum.

Removing restaurants from Rush could help Uber streamline its dispatches, especially if those restaurants migrate to Eats. While Uber will likely continue to face supply constraints from its Eats push, the food delivery platform offers a more attractive value proposition than Rush did. That’s because with Eats, customers place their orders through Uber’s app. The company collects a delivery fee ($5 in most cities), a cut of around 30% from the restaurant, and a cut of 25% to 30% from the courier on each order, rather than the flat mileage-based fees on Rush.

Uber can also book the full value of an order on Eats as revenue, or gross merchandise value (GMV), a number startups often tout to investors when they seek funding. Rush deliveries are typically placed through third parties, meaning Uber’s only revenue from each transaction is the delivery fee. “The GMV is much more attractive with people using their app,” said Adam Price, CEO of Homer, a Rush competitor in New York.

The new focus on Eats created “infighting” among Uber’s teams, tech news site The Information reported (paywall) last November, with local city managers unwilling to make drivers available to the Rush and Eats platforms. The UberRush team also reportedly hoped to cut a deal with Yelp-owned Eat24 but was blocked by people at UberEats, who had already integrated some Eat24 restaurants into the UberEats network.

This story has been updated to include additional information from Uber.