Getting elected will be the easy part for Macron; governing France is impossible

Through a combination of luck and an inspired reading of France’s rejection of its tired political establishment, Emmanuel Macron rode to a clear victory in the first round of the French presidential election. But getting elected will be easy compared to the messy business of governing a divided, conservative country.

Through a combination of luck and an inspired reading of France’s rejection of its tired political establishment, Emmanuel Macron rode to a clear victory in the first round of the French presidential election. But getting elected will be easy compared to the messy business of governing a divided, conservative country.

“We get the politicians we deserve.”

Whether Joseph de Maistre or Alexis de Tocqueville said it first doesn’t matter, the axiom is as true today as it was two centuries ago. Soon we will we find out which of two politicians my dear French compatriots deserve and how they will be governed—if such a thing as governing the French is actually possible.

(Another dose of somber and perspicacious humor from Joseph de Maistre who passed away in 1821 [as always, edits and emphasis mine]):

Fake opinions are like false money, struck first of all by scoundrels and thereafter circulated by honest people who perpetuate the crime without knowing what they are doing.

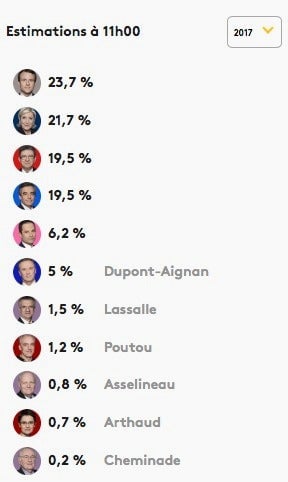

I write this with an eye on French and Swiss websites. Estimates, all caveats hereby stated, look like this:

(Official numbers will vary a little, but not significantly.)

This is interesting in a number of ways.

First, many earlier estimates had Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen neck and neck, within a fraction of a percentage point. Voters disagreed and put Macron neatly ahead of Le Pen by approximately two points. His last minute surge attests to the enthusiasm Macron has managed to arouse among French voters who are tired of the old system. A member of neither the Parti Socialiste nor Les Républicains, France’s two major political parties, Macron started his En Marche! movement (note the EM initials) just a year ago, yet he bolted ahead of the political establishment.

Second, Marine Le Pen’s advance to the run-off election on May 7th is testament to the deep dissatisfaction with globalization, Europe, the Euro, and the work of the previous Sarkozy and Hollande administrations that many French citizens feel. Like Macron’s, Le Pen’s victory in round one is a disavowal of both historic Left and Right ideologies and apparatchiks. Her score, close to 22% (much higher than the surprising 17% that was achieved by her father Jean-Marie in the 2002 election), isn’t unexpected, but it is, nonetheless, an outstanding achievement that’s shouldn’t be misunderestimated.

Third, Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s score, close to 20%, is historically (that word again, and correctly so) high and also attests to the strong disapproval of the main Left/Right parties. Mélenchon’s extremist views—a new constitution, leave Europe and the Euro, 100% tax above 400,000€ ($430,000) in income, praise of Venezuela’s dictators—were served by the superb rhetoric of a gifted tribune. As an orator he’s the best in the field—and therefore commensurably dangerous.

Fourth, the amazing collapse of the official Socialist party candidate (Benoît Hamon), with barely more than 6% of votes. This stems from François Hollande’s stunning failure to govern, which earned him a never-seen-before nadir of 21% approval in 2015. (Hollande “bounced back” to 35% in 2016, but only after announcing he wouldn’t seek reelection.)

Fifth, the vertigo-inducing trajectory of François Fillon’s fall from grace. After a surprisingly strong win in his LR party’s primary, Fillon looked like a shoe-in for the presidency. An experienced politician with the calm, rational gravitas of a former prime minister, Fillon was on his way to the Elysée palace until a string of embarrassing affairs—from questionable consulting agreements and remunerations for his spouse and children, to gifts of a pair of $6,000 suits and luxury watches—led to judicial inquisitions and a severely diminished credibility. As a result, Fillon comes in third with an estimated 19.5% of votes, tantalizingly close to a place in the second round, hence the lightheadedness.

Now what?

A quick poll tells us that about 60% of voters plan to support Macron in the final round. No guarantees, of course, but Macron is likely to be France’s next president.

That’s a mixed blessing. Emmanuel Macron and his En Marche! movement may have changed the French political landscape, but actually governing France is well-nigh impossible. In spite of its leftist postures, this is a very conservative culture, as in nothing new should ever be done. Every significant reform finds strong opposition at one end or the other of the political spectrum. François de Closets, the great journalist and author, summarized presidential predicament in two felicitously titled books: Toujours plus! (Always More!)—that is, no taking anything away, always adding spending and entitlements—and Le Divorce Français, (The French Divorce)—the people against its elites, the elites against the people.

Getting elected is going to prove the easy, quick part—an astonishing, admirable blitz operation. The travails of getting France out of its old rut will be a different story. Many of us, including all the expats who voted en masse, wish him to be the one with the pure heart who pulls the sword out of the stone.