When he was growing up, Vik Sohonie moved around a lot with his family. Born in India, he was raised in various places in southeast Asia and the United States, and spent extended periods in Europe and Africa. To stay anchored wherever he ended up, he recalls, he listened to music. “I always saw music not only as what people listen to and enjoy, but as a gateway to other cultures,” he said.

After getting a master’s degree in journalism and working for international media outlets including Reuters, Sohonie wanted a project that combined his passion for storytelling and music. He was especially interested in African music, much of which is overlooked globally.

And so was born the idea of Ostinato Records, a New York-based label that documents music from the African continent and diaspora. Sohonie has his work cut out for him, as he specifically goes in search of lost or rare music.

Ostinato isn’t alone in this pursuit: Over the last decade, independent labels run by ethno-musicologists have sprung up across the world, unearthing a treasure trove of African music. From Analog Africa to Sublime Frequencies, Sahel Sounds, and Awesome Tapes from Africa, all these projects aim to explore and curate the continent’s diverse musical offerings, and hopefully rescue them—and the musicians who made them—from obscurity.

Last week, Sohonie was a speaker at the 2017 TEDx Mogadishu, where he talked about his company’s efforts to digitize a third of the 10,000-tape archive stored at the Red Sea Foundation in Somaliland—considered the largest Somali cassette tape archive of its kind anywhere in the world.

Through his label, Sohonie also documents the music of displacement, and how political and economic uncertainty affects the diffusion or demise of certain music rhythms and genres. In July 2016, Ostinato released “Tanbou Toujou Lou,” a 20-track album that captures the diversity of Haitian music style from the 1960s and 1970s. The record’s music features Haitian Vodou drumming mixed with Colombian and Dominican merengue, capped with saxophone arrangements. Sohonie says that many of these records were lost or destroyed during the 2010 earthquake.

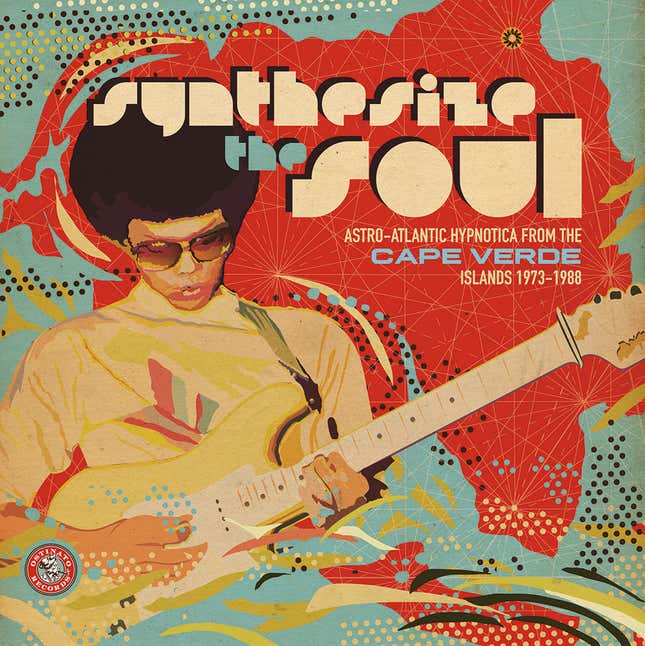

In February, Ostinato released “Synthesize the Soul,” an 18-track compilation that sheds light on how Cape Verdean musicians pioneered and influenced the electronic music that dominated international airwaves in the 1980s. As the funanà music and dance met the synthesizer, and as severe drought led to the emigration of many Cape Verdeans, the syncopated rhythms they produced, Sohonie says, helped pioneer in the electronic music movement. Today, more people from the islands live outside the country than inside it.

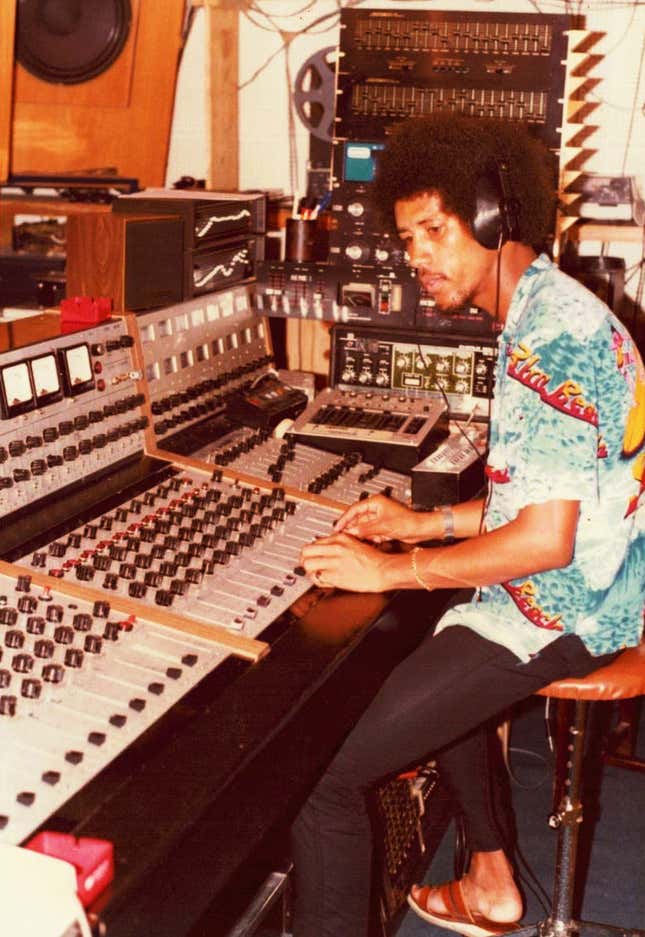

In Somalia, a country torn apart by war, Sohonie found thousands of cassettes with music from the 1970s and 1980s. The resulting mixtape will be launched later in the year and will feature the rich music of a country that embraced funk and experimented with instruments such as the oud, guitar, and accordion. Sohonie also has projects from Djibouti and Sudan in the works.

Quartz Africa spoke to him about the process of finding, sifting and compiling some of these African gems.

Ostinato Record works to capture music from countries that have experienced trauma and displacement. Why is that?

The cultures that I focused on, I only noticed it after the fact. The initial draw for Haiti and Somalia, in particular, was that we’ve been fed this single story about these countries. The stories coming from these places lacked so much perspective and history.

And I realized that I was most likely drawn to these music cultures, people, and their story because even though I have never had to forcibly move homes—I have never been a refugee—I still moved around a lot as a child, even though I moved in far less trying circumstances. So I think naturally I am drawn to cultures that have experiences with having to pick up and move and go somewhere else and readjust.

What happens when you travel to a country or a city in search of lost music treasures?

It’s quite a long, drawn-out process. What you have to do in advance is to look through various resources, like there are so many music groups on Facebook where people are sharing music.

Most music producers try and identify music talent. I try to identify research talent and work with researchers and music collectors who have incredible knowledge of the music. And then when I am in the country, I have a little bit of a roadmap because I’ve done some research beforehand. I know the name, I know the artists, I know the era I am trying to focus on.

So Haiti for example, I actually began the research in New York City. I put up an advertisement on a local Haitian radio saying “If you have any records, please give me a call.” So I was able to find an amazing cache of music within the Haitian diaspora.

Once I have tracked down all the records, I try and meet with people who really know their music heritage and culture. That usually tends to be people at radio stations, who have been working at these iconic radio stations for a long time. In Haiti, I found over 1,000 records, maybe close to 2,000 records. From then, I listen to everything and I try to distill that down into something that I think really tells the best panoramic story of that country’s past historical heritage. Something that encompasses all the style, all the influences, something that would really do justice—not only to someone who had no idea about the culture, but even for someone from Haiti.

Once I have distilled those tracks down, then begins the process of finding the musicians themselves and perhaps if there were producers behind the songs. Sometimes those albums were privately recorded by the musicians themselves. Sometimes there was a production company or record label back in the day that produced these records.

In Somalia, all this music was produced under Siad Barre who oversaw a Socialist, authoritarian regime. He nationalized the music industry. He nationalized the art. So there were absolutely no private record labels. There were some private bands but most of the music was owned by the government, it was produced by the national radio, which was owned by the government. It was performed in the national theater, which was owned by the government.

We spoke to former poets and playwrights and people who worked for the cultural department of the government. They said, “Well, in Somalia, we recognize the singers. The singers are the people we tend to idolize and lionize, and these are the people that we think you should be getting the copyrights from. They are the ones who we believe have the ownership.” So it’s a very fluid kind of approach to the copyright. It’s just about making sure that you have a good sense of fairness and making sure that the right people get their due rewards.

Ostinato Records has produced two albums so far. How did they fare in the market?

My Haitian compilation got really great reviews but the tracks didn’t sell as I would have liked because I was a newcomer to the market. But because I think Cape Verde is such a cross-cultural hub taking influences from every part of the Atlantic, it’s very easy for that music to resonate with almost anyone who has grown up in the last 30 years. I am happy to say the Cape Verdean compilation did so well. It actually sold out to the point that I had to produce more copies to meet demand.

What can people do to preserve and pass on these music artifacts?

I would say if you have these cassettes lying around, try to contact people who work in archiving. Or even the radio stations who themselves are trying to preserve their own archives. Try and give it to them because they will make the effort, in alliance with people like myself, to make sure those records are digitized or kept safe—or even perhaps commercially released again, where they can start generating some kind of income for these musicians.

This interview was edited for length and clarity