The tragic twilight of the forgotten comic-book mastermind who created Rocket Raccoon

Far Rockaway is where New York deposits residents it doesn’t know what to do with.

Far Rockaway is where New York deposits residents it doesn’t know what to do with.

On the outer fringes of the city, the Queens neighborhood—first developed as a beach resort for vacationing city dwellers—is now a collection of beaten down homes and grim apartments, under the flight path of 747s leaving nearby JFK airport for more attractive destinations. On a warm morning, I drove there to visit Bill Mantlo at the Queens Nassau Rehabilitation & Nursing Center. As I arrived, 30 members of a motorcycle gang were revving their engines in front of the building. (They were visiting a fallen brother on his birthday.)

Mantlo is largely forgotten now, a journeyman writer who worked in the 1970s and ’80s. Mantlo was one of the many comic creators who toiled in obscurity, cranking out 22-page stories for 40-cent comics. They labored under “work-for-hire” contracts that didn’t grant them ownership of their creations, and most had no ability to share in any profits they generated.

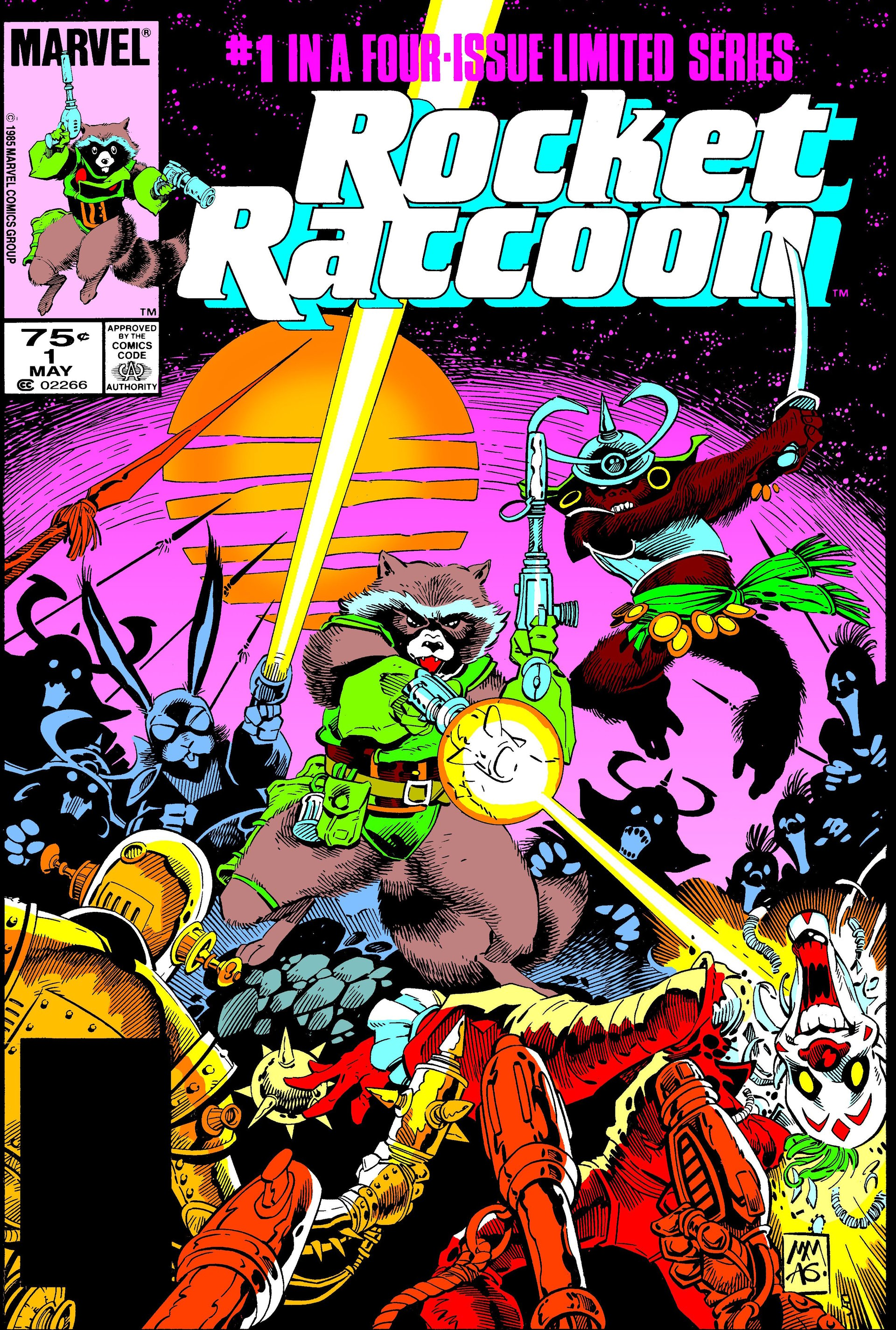

Among his characters is Rocket Raccoon, the irascible, anthropomorphic star of the Guardians of the Galaxy movies played by computer effects and Bradley Cooper. The sequel, out in the US today, is already set to be one of the highest-grossing films of the year.

In Mantlo’s era, comics were for adolescents or stunted adults, and their authors were among the most marginal of writers. Their work was sold on spinning racks in drug stores, and teachers banned them from class rooms. If superheroes were on a screen, they were in Saturday morning cartoons, or the campy 1960s Batman series. Now, superheroes are a major cultural force, studied at college seminars. Even the most visionary comic book creator couldn’t predict the flood of movies and TV shows starring their characters that would one day have been released—or the billions of dollars they’ve generated so far.

Bill’s brother Mike, who’s responsible for Bill’s care and makes monthly visits from his home in Delaware, met me in the lobby of the Queens Nassau facility. Mike prepared me in advance for our encounter: Don’t expect much.

Toiling in the ideas factory

A Queens native, Mantlo began reading comics at an early age, and soon was drawing his own. In junior high school, after getting beat up by bullies, he drew a comic starring his antagonists as superheroes. They left him alone after that.

He studied photography at Cooper Union, a renowned New York college for art and design, but was miserable working as a department store photographer after graduation. A friend helped Mantlo get a job at Marvel, where he started working in the production department. He caught his break when an editor, desperate for a quick story, gave a him a shot at scripting a horror comic. By the mid-1970s, Mantlo was plotting and scripting five or six titles a month.

In an industry that prized creativity, versatility and, above all, speed, Mantlo stood out. He specialized in jumping in when other writers missed their deadline, with an oeuvre dizzying in its variety. In a 20-year career, Mantlo wrote for more than 65 separate titles, in genres ranging from horror to kung fu, science fiction to mystery, and, of course, super heroes.

Bursting with energy, Mantlo was constantly pitching ideas for new stories. His prose was dense and overwrought, in the tradition of Marvel icon Stan Lee, and his stories inevitably featured anguished characters and tangled plots. He was a natural choice to write two of Marvel’s famously tragic heroes, Spider-Man and the Hulk, but he also took on thankless assignments like writing characters licensed from toy companies, like Rom and the Micronauts, and made them come alive.

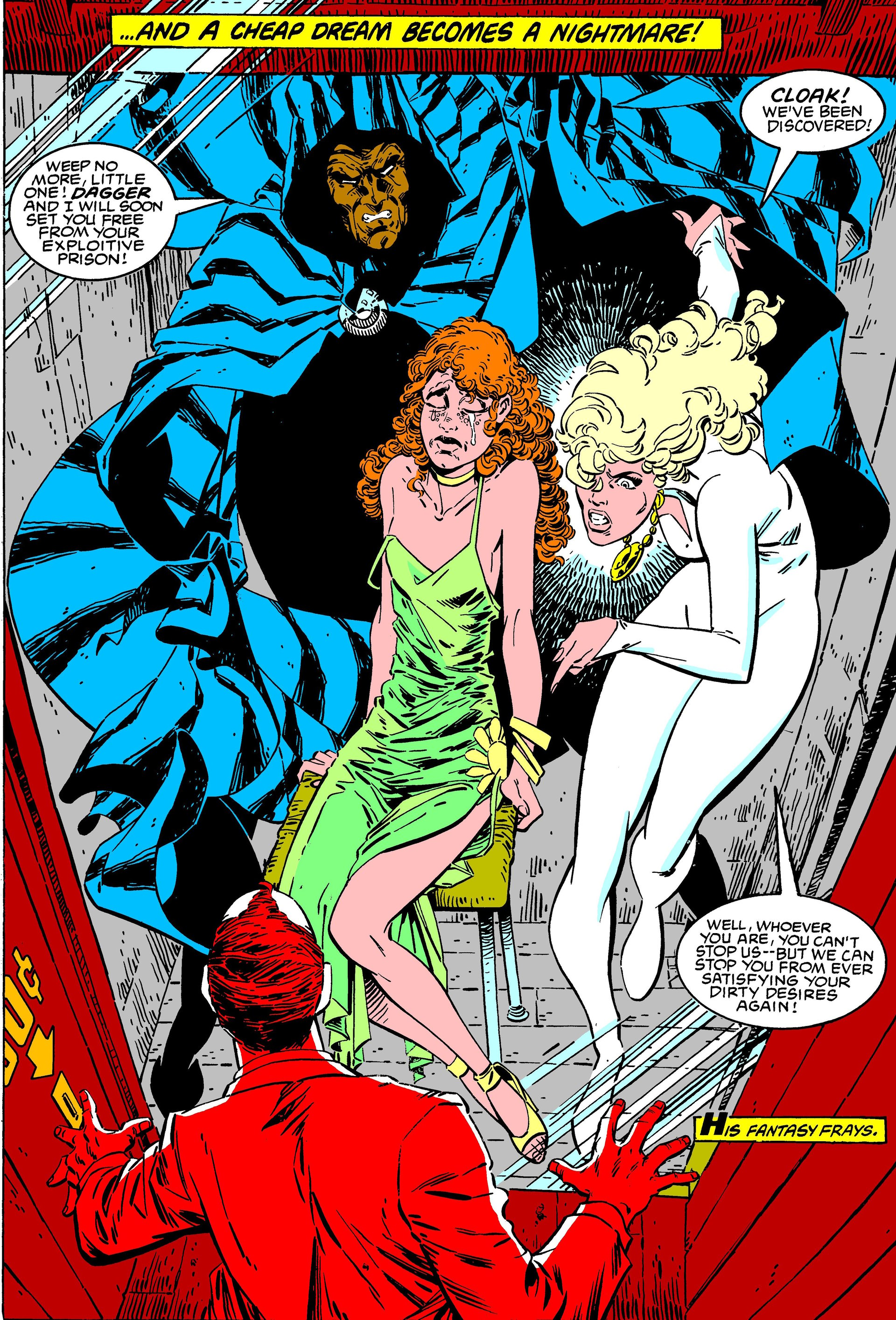

When he got a chance, he injected his own inventions into Marvel stories, drawing from his own life and an interest in social justice born from coming of age in the late Sixties. Cloak and Dagger, created for a Spider-man comic with artist Ed Hannigan, were a pair of mismatched, runaway teenagers who battled drug dealers and human traffickers.

“The thing with Bill, if you started talking about something you were interested in drawing, within 10 minutes Bill would have turned it into a project,” said Mike Mignola, an artist who worked with Mantlo on Rocket Raccoon, Alpha Flight, and other titles. “The idea of seeing so much of your creative energy going to work where you know you could do better with more time, that’s got to be frustrating.”

Mantlo longed to escape the confines of his role as a company scribe, and write about characters he owned and could profit from. As his career progressed, artists working with him could tell his heart wasn’t always in it. His reputation as an “emergency fill-in guy” came to haunt him, as he was overlooked for more plum assignments, said Carl Potts, who edited Mantlo on Rocket Raccoon and Cloak and Dagger. But he made deadline.

In 1985, Mantlo and artist Butch Guice launched Swords of the Swashbucklers, a comic about space pirates, for Epic, a new Marvel imprint for creator-owned projects. The comic never caught fire, and by the late Eighties, Mantlo’s relationship with Marvel and its leadership was fraying. Clashes with Marvel’s executives and its legal department helped lead him to enroll at Brooklyn Law School.

Drawn to the drama of the courtroom, Mantlo began working for the Legal Aid Society. On the side, he continued to write the occasional comic for DC, Marvel’s chief competitor and owner of Superman and Batman, and offered free legal advice to comic creators fighting for ownership of their characters.

“I want to be a real superhero, to really fight for people,” he told his daughter, Corinna, then eight years old.

Soon after he left comics in the early 1990s, the industry changed radically with the advent of Image comics, a new company founded by artists and writers, based on the idea that creator would retain the copyrights. Image’s comics—which included Spawn and the Walking Dead—were wildly successful and they ushered in a new era of creator-driven comics.

“That’s where everyone said, ‘Now I get it, these guys were making millions,’” said Mignola, who went on to create Hellboy for Dark Horse comics under a contract that gave him control of the movie rights. The two Hellboy films, released in 2004 and 2008, have so far grossed $260 million.

Mantlo never got to enjoy that success. He barely knows he was a comic writer. In 1992, Mantlo was struck by a hit-and-run driver and suffered severe and permanent brain injury. He’s spent the last two decades at the nursing facility in Far Rockaway, rarely receiving visitors, lying in bed with his eyes closed.

A life reduced

On a Friday afternoon, ahead of a summer weekend, Mantlo left work in the Bronx early and was roller blading home. He was four blocks from his Upper West Side apartment when he was blindsided by a car. A witness said his head hit first the wind shield, then the pavement. While his other injuries were not serious, he incurred traumatic brain damage. He wasn’t wearing a helmet.

After two weeks in a coma, Mantlo slowly regained some functions, but didn’t speak for four or five months. He moved through a series of rehabilitation facilities in five states, and was seen by a number of specialists, but after several years with little progress, he was admitted to the Queens Nassau rehabilitation center in 1995, where he has been ever since. His brother Mike became his legal guardian since Bill was now divorced and his daughter was a minor.

He’s able to walk, Mike explains, but he’s unwilling to, and so over the decades his leg muscles have atrophied. There’s no television or radio—Bill finds them distressing—and he takes his meals in bed. When offered opportunities by attendants to leave his room or venture outside, he resists.

Bill, now 65, lay in bed, wearing a long-sleeved, green T-shirt, his thin body wrapped in a blanket. His thinning gray hair is cropped short, his nails are long, his teeth are in need of attention.

The ground floor room is small and dimly lit. It smells of a half-eaten lunch, pushed into a corner on a hospital tray. One window lets in sunlight. On the walls are taped drawings he’s been sent by friends and fans; print outs of covers from his most memorable characters; and photos of a long-haired, smiling Bill before his accident.

His life is now reduced to this 15-by-30-foot room. An imagination that once traveled through time and across galaxies is now trapped, probably forever, within his damaged mind.

I approach him cautiously. His eyes are wild, searching, as his brother explains who I was. He seems puzzled, not understanding why I’m there.

I ask some basic questions, and he answers, after a fashion. When I ask if he has a favorite creation, he answers “Dagger”—drawing out the word out of his mouth very slowly, referring to the female half of Cloak and Dagger, a lithe teenage ballerina turned vengeful heroine. I mention I spoke to his former Marvel editor, Carl Potts, and he responds, “Goooood man.”

Making movies

Mantlo’s care is expensive, and his care is now covered by Medicaid. While his family hoped to one day move him out of the Queens Nassau facility, it looked like he would spend the rest of his life in Far Rockaway. His outlook began to change about a decade ago, when Marvel entered the movie business, and needed to ensure it owned the film rights to its thousands of characters created over decades by artists and writers like Mantlo.

Ownership of copyrights has been a contentious issue in the comic book industry. Marvel spent years battling the estate of Jack Kirby—co-creator of seminal properties like the Fantastic Four, Hulk, Thor and the X-Men—over the rights of the characters. The Kirby family argued that, under a provision of copyright law, the rights reverted to their creator after a set period, and if they prevailed in court, the legal status of many of its characters would be thrown into doubt.

To prevent similar disputes, Marvel approached its creators and offered them payments, said to be as low as $500, to lock up the rights to their characters. Some took the initial offer, while others—like Mike Mantlo—hired attorneys to hammer out contracts. (The Kirby estate and Marvel settled in 2014. A Marvel spokesman disputed the $500 figure, calling it significantly less than what they offered, and said the decision to pay creators for the rights was unrelated to the Kirby suit).

In 2009, Disney acquired Marvel for $4 billion, a purchase that included the rights to more than 5,000 Marvel characters.

Marvel’s executives, many of them former comic collectors and creators who knew Mantlo and his story, were sympathetic to his condition, says Lawrence Klein, his lawyer. “There were people at Marvel who wanted to do the right thing,” Klein said of the negotiations. “But they needed someone like me on the other side to push them to push their higher ups to do the right thing.”

As a result of that foresight, Bill Mantlo received a significant sum for the use of Rocket Raccoon from the first Guardians of the Galaxy movie, which was just a rumor when the contract was signed. Mike won’t disclose the amount, but says Marvel “stepped up big time.” Bill was also treated to an advanced screening of the film by Marvel executives, who wheeled a television into his room.

The first movie, released in 2014, earned an astonishing $771 million. Mantlo is thanked in the closing credits.

The royalties from Marvel have allowed Mike to purchase a mobile home for Bill, which he’s installed on his property in Delaware, and to ensure he’ll receive 24-hour care. Mike is in the process of getting the New York courts to allow him to move his brother to Delaware, and he’s hopeful Bill will move out of the nursing home by the end of the year. Mike’s decisions about his brother’s care have caused fissures within his family; Corrina Mantlo questions whether living in a mobile home will be the best situation for her father. Still, “I would love nothing more than to see him get out of the hospital,” she says.

There may be future income streams as well. After years of false starts, Cloak and Dagger are set to feature in a TV show, set to debut next year on Freeform, a cable station owned by Disney. In all, Marvel holds the rights to more than 60 of Mantlo’s characters.

Given Mantlo’s inventiveness and drive, it’s hard to think he wouldn’t have found success in this new era with characters he owned. Movies based on Marvel characters have so far grossed $9.1 billion. Even if he didn’t strike it rich, Mantlo probably would have enjoyed working on characters of his own invention while attending to his legal practice.

“He would have done what he wanted to, what he cared about, and hoped that one of them hit,” Mignola said. “That is kind of the dream.”

Back in his room in Far Rockaway, Mantlo is becoming agitated. The presence of men bother him, and he begins to bellow “No man!” in my direction, and flips me the bird. He pulls his covers over his head. I back away, and he relaxes, as if my presence no longer registers.

Women are no problem, though. He delights in the attention of his sister-in-law, Liz, who sits with him, and mugs for a female photographer.

After an hour with Bill, I worry my presence is causing him distress. Before leaving, I ask him to sign a comic I brought from my collection. With a shaking hand, he scrawls “Bill” in big looping letters across the backing board of Rocket Raccoon No. 4, released in 1985.