What the Fed and the People’s Bank of China have learned from Alan Greenspan

Before the global financial crisis hit, central bankers didn’t try to deflate asset bubbles. Instead, they just waited until they popped and tried to contain the damage and pick up the pieces. But that hands-off approach appears to be no longer in vogue.

Before the global financial crisis hit, central bankers didn’t try to deflate asset bubbles. Instead, they just waited until they popped and tried to contain the damage and pick up the pieces. But that hands-off approach appears to be no longer in vogue.

The evidence? Look no further than the most recent market upheaval, which was sparked by central banks in the world’s two largest economies doing their best to deflate bubblicious conditions in key financial markets.

After a long period of accommodative policies, the People’s Bank of China essentially told the financial sector in a stern statement this morning not to expect the central bank to always be standing ready to bail them out with more liquidity. That warning came after a surge in short-term borrowing rates in government-controlled money markets that left many scratching their heads.

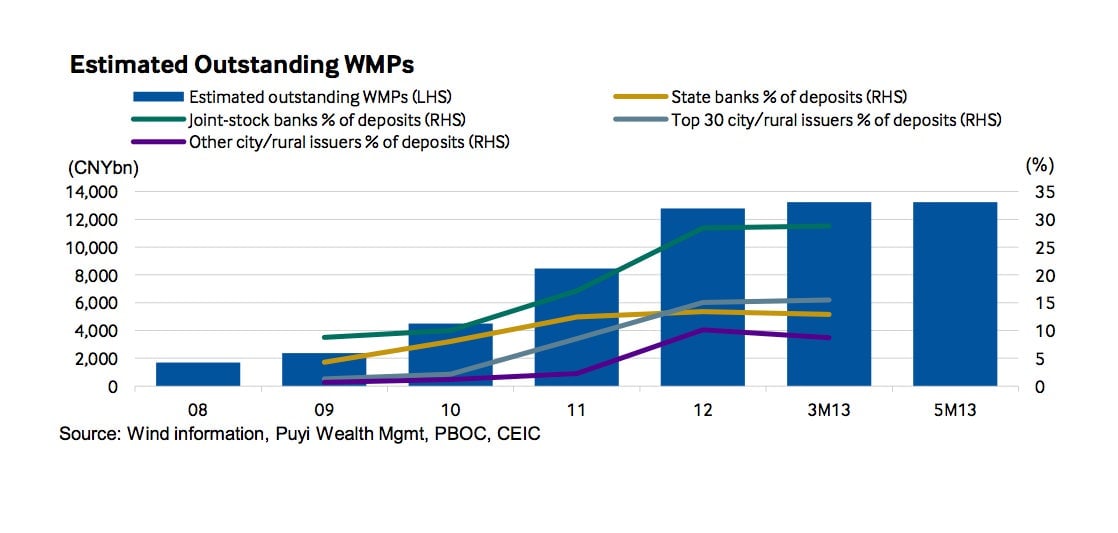

Why is China’s government doing this? For one thing, it is increasingly concerned that the shadowy lending plaguing its financial system will result in a credit crisis. A prime example is the boom in so-called “wealth management products,” which are short-term deposits invested into long-term, often dicey assets. This Fitch chart illustrates the recent surge in issuances of wealth management products.

“In our view, the PBOC is signaling to the market that it will not endlessly tolerate some banks’ reckless liquidity management and overdependence on the interbank market for facilitating their asset expansion off-balance sheets,” wrote S&P analysts in a note published Monday.

The Federal Reserve appears to be doing something similar. The economy is improving, but with the US unemployment rate at 7.6%, it’s far from strong. (The Fed’s outlooks have been optimistic, but they’ve also been consistently wrong.) If anything, the recent decline of inflation suggests that the Fed should be putting more cash into the economy, rather than talking about winding those efforts down.

And yet, Fed chief Ben Bernanke has been a tough talker lately, at least by recent standards. A logical conclusion might be that the Fed is going beyond its traditional mandate of tinkering with the real economy to tame an over-exuberant market rally—something it refused to consider under former Fed chair Alan Greenspan. He famously said that ”relying on policymakers to perceive when speculative asset bubbles have developed and then to implement timely policies to address successfully these misalignments in asset prices is simply not realistic.”

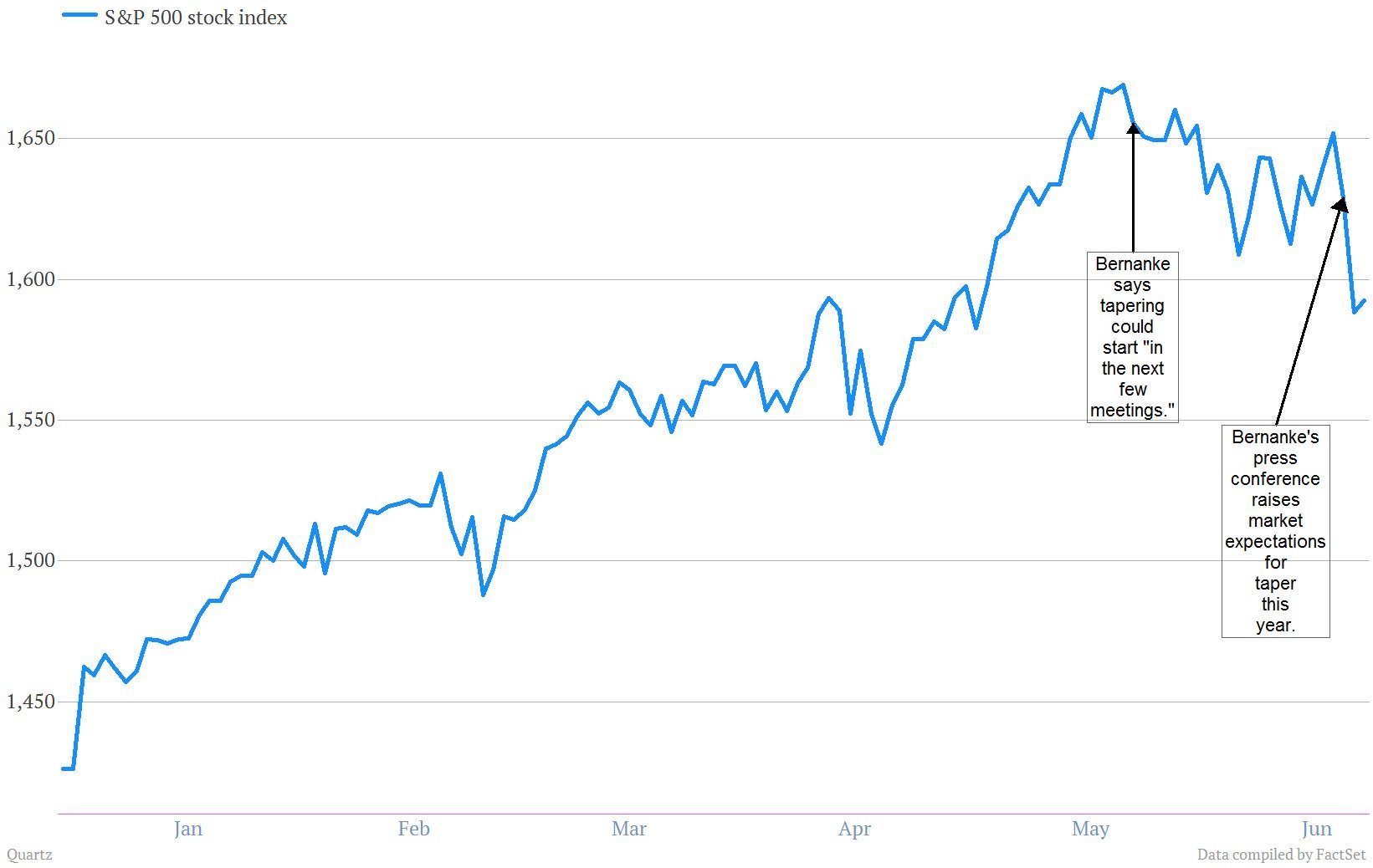

At any rate, Bernanke appears to have been signaling the markets since May 22, when he said the tapering of quantitative easing could start “in the next few meetings.” After a 16% run-up in US stocks this year, the market stopped dead in its tracks.

Another potential sign of overly-exuberant investing: covenants, the part of riskier high-yield (or junk) bond contracts that protects investors, have been weakening lately. The trend parallels the heady pre-crisis days of so-called “cov-lite” investments that left little protection for investors, and in retrospect seemed a clear sign of excess.

Of course, the Fed and the PBOC have different motivations for skimming off the froth. The PBOC seems legitimately alarmed about the stability of China’s banking system. The Fed has a more nuanced worry that bubbly markets could jeopardize economic growth when the Fed finally begins unwinding its extraordinary support. The takeaway: after the financial crisis, global central bankers seem far more willing to end a good party before it gets out of hand.