Emmanuel Macron will have to defy French culture to be an effective French leader

As another president is about to find out, getting elected is a necessary but not sufficient condition. Emmanuel Macron, if elected, will be faced with the arduous task of convincing the French to sacrifice some of their way of life for the greater good of their country, themselves, and their children.

As another president is about to find out, getting elected is a necessary but not sufficient condition. Emmanuel Macron, if elected, will be faced with the arduous task of convincing the French to sacrifice some of their way of life for the greater good of their country, themselves, and their children.

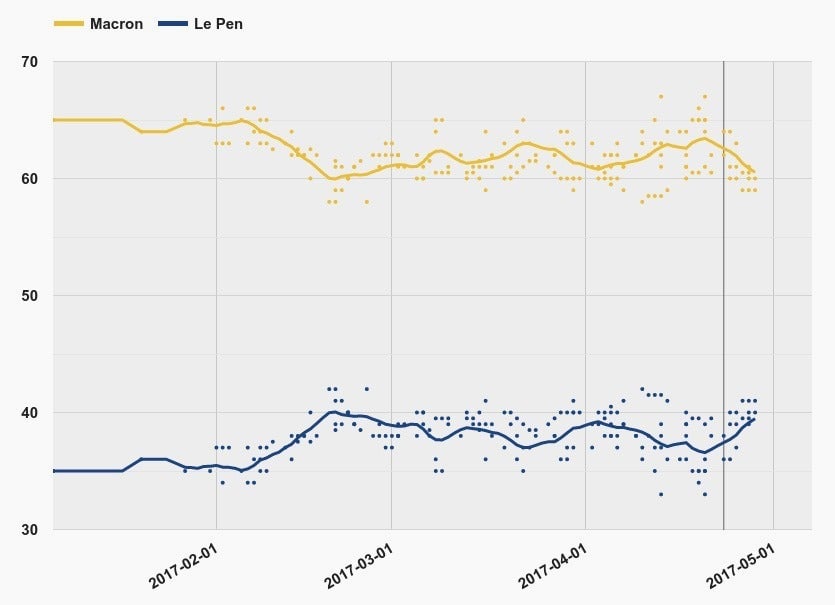

If the polls are correct, Emmanuel Macron will defeat Marine Le Pen in the French presidential run-off on May 7th (although he won’t enjoy the crushing victory of Jacques Chirac vs Le Pen père in 2002: 82% for Chirac, 18% Le Pen). Wikipedia’s remarkable compendium of polling data, in English and in French, shows Macron running at 60% as of May 1st:

(Sad to say, the Wikipedia data is much more detailed and clear than most MSM.)

Still, one week before the final round, the situation is fluid. Le Pen performs a delicate dance towards the center: She’s toned down her anti-EU stance, and has gathered support from erstwhile “Never Le Pen” politicians such as Nicolas Dupont Aignan, cruelly nicknamed Ducon Gnan-Gnan (untranslatable, for francophone readers only) by master insulter Nicolas Sarkozy.

If one extrapolates the two trend lines above—always a dangerous exercise—one could imagine Marine Le Pen scoring an upset of Trumpian proportions. But these speculations take us away from today’s topic: Macron’s Mission Impossible. Or, put slightly differently: France’s ungovernability.

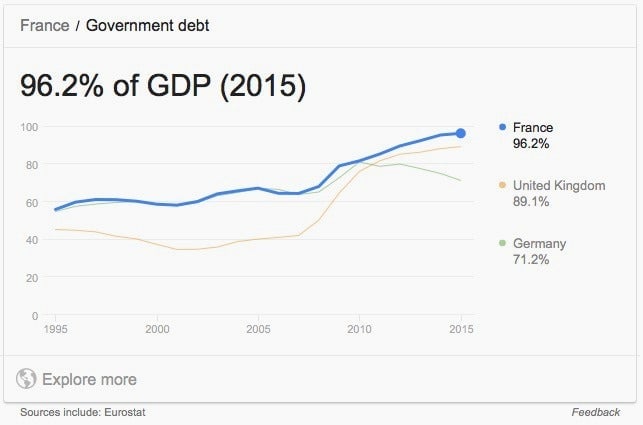

Before the Euro, France lived beyond its means and, as a result, had to regularly devalue its currency, to print fresh money to pay its debts. Each time the Franc fell, the French got a little poorer, but life continued.

Enter the European Monetary Union with its unified currency, the Euro, and its regulations. France could no longer run the printing press, but the Country of Good Sin kept living beyond its means, with government spending exceeding tax revenue. Since it couldn’t devalue the currency, France borrowed to support its lifestyle…and kept borrowing.

Today, France’s debt is close to 100% (96% in 2016) of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The following graph, shows how France differs from its neighbors. In particular, Germany’s debt is much lower and keeps decreasing:

In a not-too-distant future, France will have exhausted its borrowing power and will need to find money inside to reimburse its creditors.

Inside? Where?

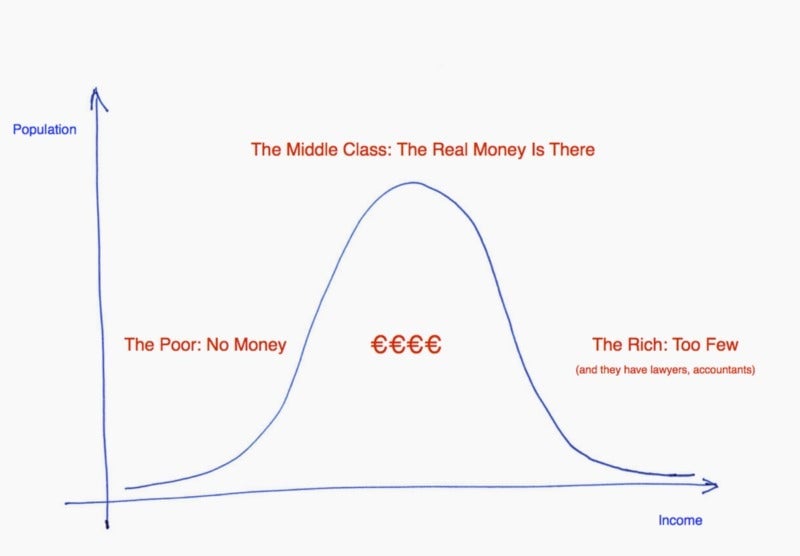

Consider this overly-simple but relevant graph:

The poor don’t have any money. The rich are too few and too armed with legal and accounting tricks. All that’s left is the middle class, where population multiplied by income yields the only place a government can mine for tax revenue.

Or…perhaps the French government could try to be less lavish.

Today, government spending reaches 56.2% of France’s GDP, versus 44% in Germany. French governments give lip service to lowering public spending, only to increase it year after year. Why? Because of the voting power of those on governmental and para-governmental payrolls—they make up about 40% of the population, they’re protected by regulations and unions, and they won’t be sheared.

The attraction to government-protected jobs is an old component of French culture. In de Tocqueville’s The Old Regime and the Revolution, there are multiple references to a deeply ingrained thirst for “offices,” i.e. posts that are granted and protected by the king:

It is a grave error to suppose that the rage for office-seeking, which stamps the French of our day, the middle classes especially, sprung up since the Revolution: it dates from a much more ancient period, though constant encouragement has steadily developed and intensified it.

Regardless of how venerable the vocation, I can remember when public employment meant trading lower wages for job security. Now public servants often get both higher wages and guaranteed employment.

There are other obstacles to moderate spending: A convoluted and opaque tax code that’s immune to change because no one really understands it, or an equally inextricable system of entitlements such as rules for retirement age and pensions.

How will France’s new president defeat this entrenched opposition to change?

Let’s assume that the En Marche! leader is elected on May 7th. A few short weeks after his ascendency, there will be parliamentary elections. He will need to win enough of a majority to actually govern, to get the laws he needs to enact the reforms he promises.

This is a much harder task than defeating a dozen would-be presidents. In the parliamentary elections, there’s only one Macron and 577 seats in play. If his hand-picked candidates don’t win enough seats, Macron will have to enter the world of compromise in order to forge needed alliances. Actually, he’s already started in allying himself with perennially unsuccessful centrist presidential candidate François Bayrou, one of the oldest crocodiles in the bayou. (Bayrou is savagely ridiculed in Houellebecq’s superb political fiction novel Submission.)

At critical junctures, when crucial reforms face real opposition, we’ll witness the real test of Macron’s political skills, his ability to speak directly to French citizens above the din of blustery politicians. Leadership manifests itself in two states; it either creates an energy field, like a magnet, or it channels, gathers, and reorients other peoples’ power. Macron will need both kinds to convince people to give up something for France’s (and their) greater good.

Can he do it? Let’s keep in mind that Macron has never held elected office. A member of the Socialist party from 2006 to 2009, Macron was briefly president Hollande’s economic adviser, and was later appointed, again briefly, as economics minister before resigning to found his En Marche! movement last Apr. 2016. But he’s now ready to climb the steps to France’s highest office?

On the other hand, he’s a classical product of France’s elite education system, seemingly groomed for office. After private Catholic school in Amiens and the high-octane Lycée Henri-IV, Macron studied philosophy at Nanterre University near Paris, was an editorial assistant to prominent philosopher Paul Ricoeur, went to Sciences-Po, and scored 5th in ENA’s (National School of Administration) admissions contest. Very few members of France’s nomenklatura are not énarques, alumni of this top government nursery. Of note, before advising Hollande, Macron was an investment banker at Rothschild & Cie, another presidential nursery, recalling that Georges Pompidou also worked there from 1953 to 1962 before winning the presidency in 1969. The Rothschilds have good taste.

France has never had such a young and inexperienced president. The youngest before him was another énarque with extensive parliamentary and ministerial experience, Giscard d’Estaing, who was 48 years old when he was narrowly elected in 1974 with 50.7% of the vote.

If Macron succeeds and is reelected, he’ll have had 10 years to reshape France’s economy, to rejuvenate its culture in his image and to earn a unique place in the country’s history.

If he fails—if Macron can’t get enough parliamentary support, if he can’t convince French people they need to take better care of their country for themselves and their children—Marine Le Pen will be elected in 2022 (unless one of the financial shenanigans she’s accused of disqualifies her).

Let’s carefully watch how the June 11th and 18th parliamentary elections take shape.

* * *

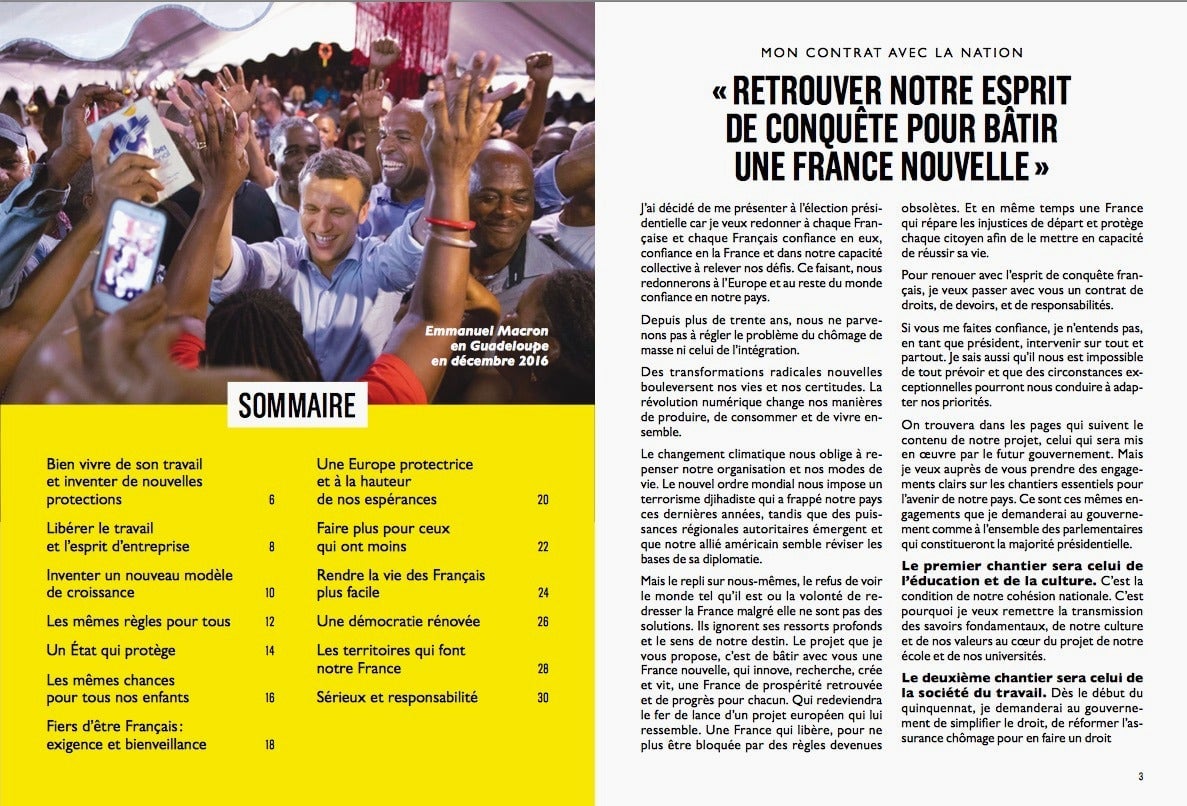

Afterword: Last year, Macron published a combined life story and personal statement titled “Revolution.” I found it a bit too 360º, a sort of Theory of Everything—attractive ideas, a little too impossible to disagree with at times, but few concrete priorities; where will we start and what will we put aside for later? There is more detail and less length in his campaign manifesto whose first two pages are reproduced below:

Further light is shed by Anne Fulda’s bio titled Emmanuel Macron: un jeune homme is parfait (Emmanuel Macron: Such a perfect young man). The highly readable book, not yet translated into English, is well documented, alertly written, filled with insights on Macron’s character and powers of seduction. The Telegraph offers a short translated extract that unfortunately and unsurprisingly focuses more on Macron’s personal life than on his politics and leadership skills.