Target used 16,000 eggs to decorate a dinner party, in a grand display of design’s wastefulness

Designers love eggs. Often used as a visual metaphor to illustrate concepts like “hatching ideas,” “growing potential,” or “new beginnings,” the humble chicken egg appears on book jackets, album covers, Twitter avatars, bank advertisements. The egg has also inspired several designer chairs and a wave of ovoid architecture.

Designers love eggs. Often used as a visual metaphor to illustrate concepts like “hatching ideas,” “growing potential,” or “new beginnings,” the humble chicken egg appears on book jackets, album covers, Twitter avatars, bank advertisements. The egg has also inspired several designer chairs and a wave of ovoid architecture.

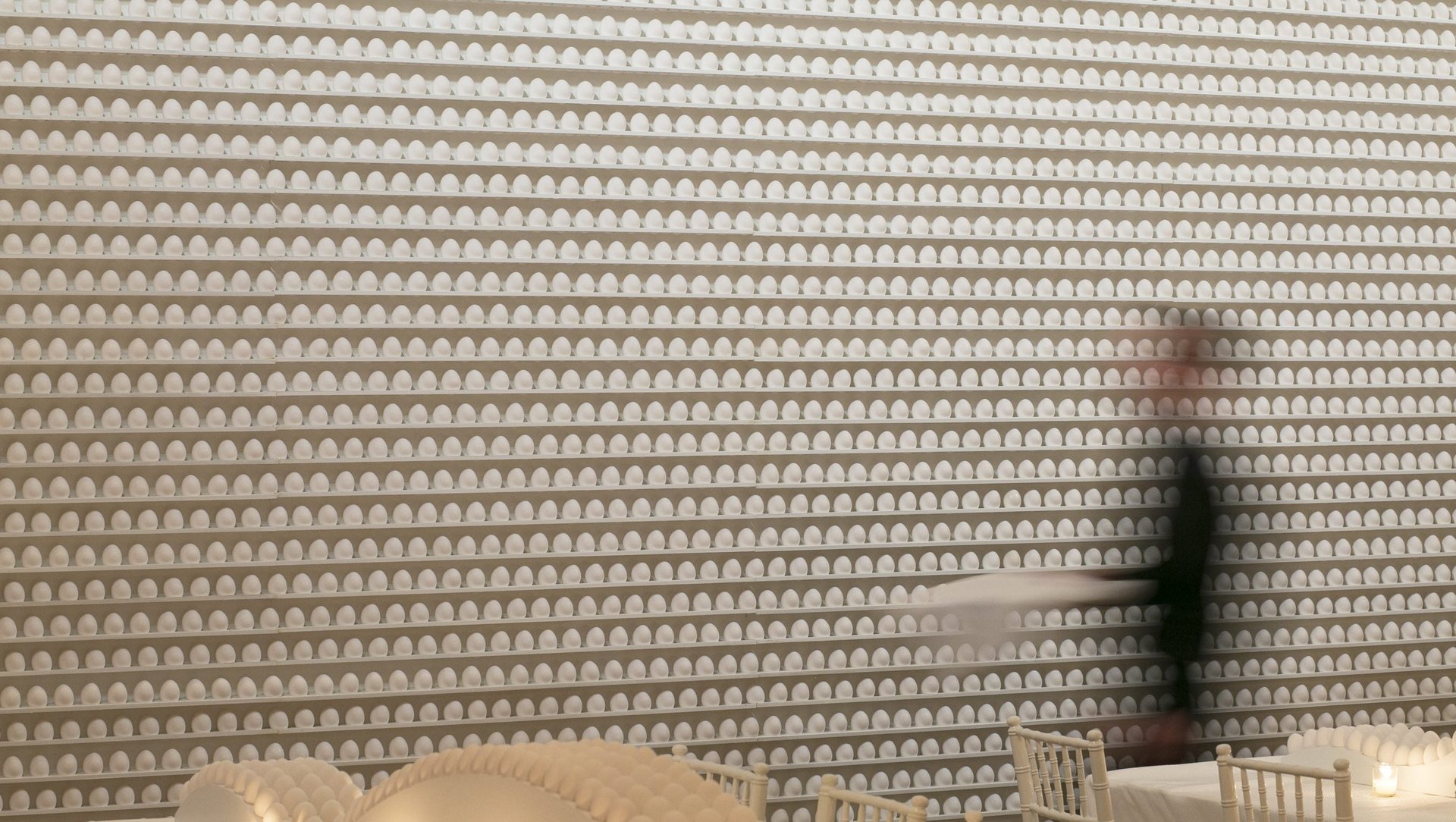

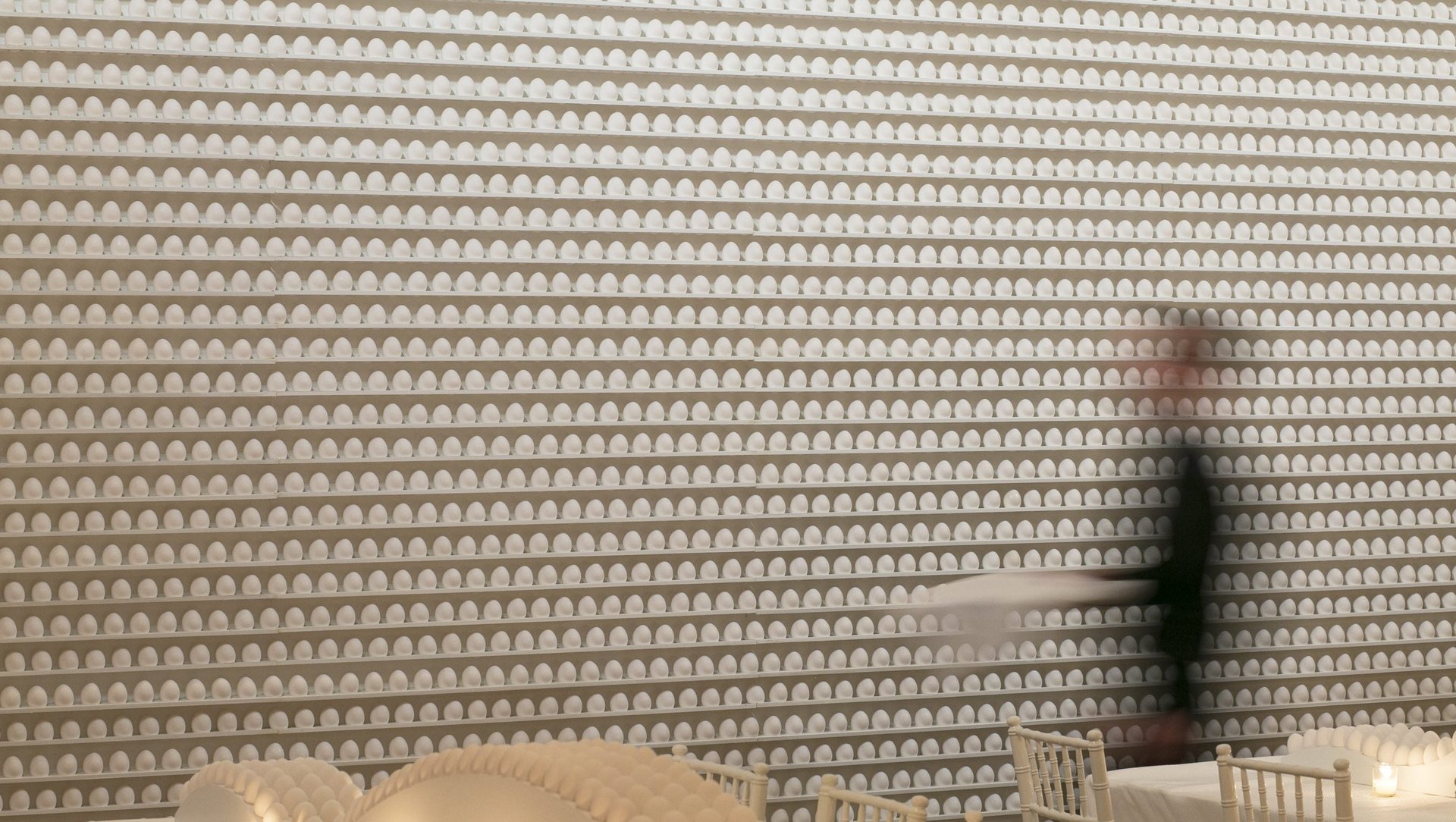

At a Target-sponsored private dinner on April 25 during the TED conference, designers erected an altar to their favorite motif. The 16,000 fresh chicken eggs meticulously arranged in endless rows were meant to illustrate the conference’s theme, The Future You. “The egg symbolizes potential for the future—a fitting theme for an evening of thought-provoking conversation and connection,” Target explained in a blog post two days later. The “progressive dinner” for select TED attendees was held at Vancouver’s Stanley Park Pavilion and co-hosted with the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Event designer David Stark describes the main installation as a “grand wall of white eggs lined up, floor to ceiling, like soldiers.” He decorated the tables with “undulating ‘hills’ of white eggs,” and filled a second room with brown eggs. To start the festivities, Target chief creative officer Todd Waterbury and Cooper-Hewitt director Caroline Baumann asked guests to use tiny wooden mallets to whack open some eggs. Inserted within the hollowed out eggs were tightly rolled chits of paper that indicated the guests’ seating assignments.

Many attendees, including several design luminaries, cooed about the smashing spectacle.

Indeed, being in proximity to so many real, breakable eggs triggers wild possibilities: Will someone smash the great wall of eggs? How many omelets can one make with 16,000 eggs? How many chickens did it take to lay this decor?

And perhaps most importantly: What happens to all those eggs when the party’s over? Target swiped away any concerns by pointing out that the eggs were all donated afterwards. So there.

But that’s not the end of the story.

At least one attendee, who declined to be named for this article, was bothered by the excess of the egg display. “It began to feel pretty self-indulgent,” she told Quartz. “Was using so much food as decoration really the best way to talk about the future?”

Target says it doesn’t see the problem with using 16,000 edible eggs as art supplies. “No, I didn’t feel it was wasteful,” said Stark. “We gave business to a local farm that employed a community of people, and then those eggs went on to nourish animals at another nearby farm.”

Cooper-Hewitt declined to comment for this story but did post an Instagram from the lavishly-produced dinner, assuring fans that the eggs were “donated to local organizations.”

Donating isn’t a panacea

So where did the 16,000 eggs actually go? We followed the egg trail and verified that Target ordered edible Grade A eggs (perfectly formed eggs with a clean shell and a well centered yolk) from British Columbia’s largest industrial egg plant, Golden Valley Foods. Golden Valley Foods’ sales manager says that the “eggs for art” was an unusual request but fulfilling the order was no problem because the facility handles a million dozen eggs a week.

After the dinner, the eggs were given to a pig farm, not a food bank as some dinner guests believed. Vancouver’s food bank refused the donation because federal health guidelines require that raw eggs for human consumption are kept refrigerated at 40° F or below to prevent salmonella. Between the set-up and the dismantling, the 16,000 eggs were kept at room temperature for several days.

[protected-iframe id=”9a895cef5bbbfba55403e14da46c663c-39587363-78626586″ info=”https://www.facebook.com/plugins/post.php?href=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2FBlueSkyMeat%2Fposts%2F1627234877306041&width=500″ width=”500″ height=”644″ frameborder=”0″ style=”border: none; overflow: hidden;” scrolling=”no”]

Thousands of eggs would have been destined for the dumpster if Blue Sky Ranch, a pig farm a 3.5 hours drive away from Vancouver, had not agreed to pick them up. But upcycling Target’s discards came at a great cost, says ranch co-founder Julia Smith. She explains that farms often get calls for donated food—vegetables, yogurt, whey, chocolate cake—but they’re expected to shoulder the costs of transporting the goods and discarding the packaging material afterwards. “It’s very labor intensive,” Smith tells Quartz. “From a purely economic argument, it doesn’t make sense.”

She agreed to accept Target’s discarded eggs because they would be a good source of protein for her pigs, she said, and because she felt it was “the right thing to do.” But receiving 16,000 eggs was overwhelming for the scale of her farm operations, says Smith. To feed about 200 hogs, farmers have to boil the eggs each morning. (Boiling eggs safeguards against biotin deficiencies caused by overconsumption of raw egg whites.) Smith says that as of May 9, the farm still had three weeks’ worth of eggs to go through.

Smith said that Blue Sky’s heritage pigs are usually fed a diet of non-GMO foods, but she found it unconscionable to let Target’s trove of industrial mass-produced eggs go to the dumpster. “The only thing worse than producing eggs with hens in cages and feeding them GMO feed is doing all of that and then throwing them in the garbage,” says Smith. “We are just absorbing their waste.”

Recycling clichés

This is far from the first grand gesture involving food—and food waste—in design. With the pressure to push creative boundaries, designers often go to extremes for out-of-the-box concepts (Lady Gaga’s “meat dress” comes to mind). Organizers of 2015’s food-themed World Expo in Milan, for example, grappled with the paradox of promoting sustainable food practices vis-a-vis the ”culture of waste” displayed in elaborate pavilions that were torn down after the six-month fair.

Designers love to tout the circularity of recycling as a concept: ”The farms in this network are a united front on sustainability,” said Stark, referring to Golden Valley Foods and Blue Sky Ranch. “To me, that’s a full circle idea without waste.”

But this neat, zero-waste circle is a fantasy. Granted, there more egregious examples of wastefulness in the name of creativity, but Target’s unapologetic display of food slowly becoming unfit for human consumption, and its naive notions about recycling, should give us pause.

Stark is a designer who clearly does care about sustainability, and his efforts to find an alternative plan when food banks rejected the eggs is commendable. But pressing thousands of unwanted eggs upon a pig farm, though well-meaning, is an example of what sustainability advocates call the fallacy of conscious consumerism.

For an industry so obsessed with nuanced symbolism, designers could learn to expand their repertoire beyond aesthetics and consider the true cost of their grand ideas.