Side-by-side images expose a glitch in Google’s maps

If your city is not on Google maps, does that mean you don’t exist? In some cases, yes.

If your city is not on Google maps, does that mean you don’t exist? In some cases, yes.

For all the vast amounts of location-based data that Google has, there are still places that are impossible for the company to map. Though these elusive spots can be captured by satellite and aerial imagery, on Google’s maps they simple show up as blank.

For instance, Google lacks mapping data on most favelas, Brazil’s infamous urban shantytowns (though not for lack of trying). In Rio de Janeiro, only 26 of the city’s 1,000 favelas are mapped—this despite the fact that the favelas are home to over a million people and about a quarter of the city’s population.

Here is Morro dos Prazeres, a favela in the heart of Rio de Janeiro.

It’s not just Brazil’s favelas.

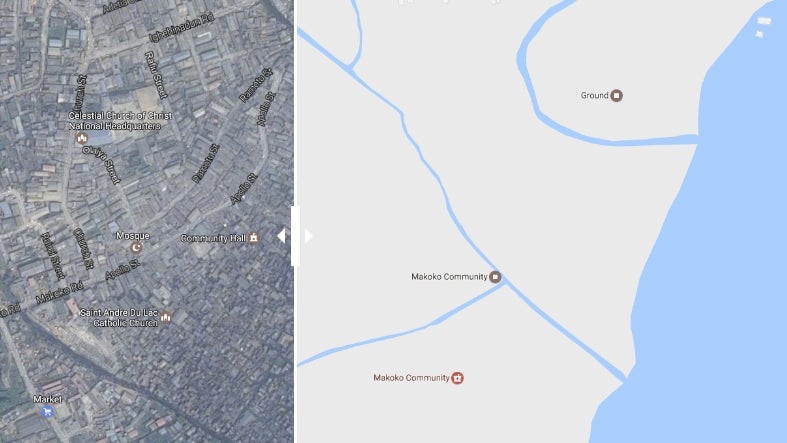

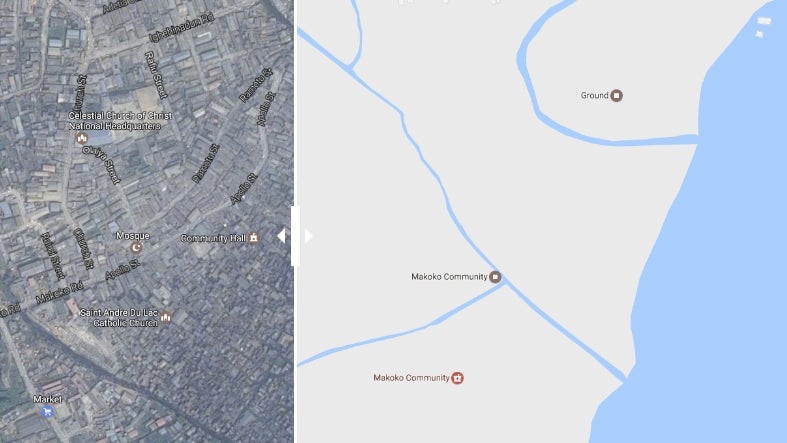

Makoko, a floating lake community off the coast of Lagos, is one of the city’s best-known lagoon settlements. Estimates of population place the community at around 100,000 inhabitants, but on the map the settlement shows up as blank space.

Parts of the Ömnögovi Province, situated within the Gobi Desert in Mongolia, are sparse and distant enough to have escaped any representation on the company’s digital maps.

And Chad’s Lake Fitri drainage basin has seen a similar fate. Though it is home to almost two million people, the majority of the region’s settlements are virtually invisible on the map.

There are worrying consequences to being invisible on Google Maps. Humanitarian organizations have decried Chad’s lack of geographic data as an impediment when it comes to determining how to distribute resources in times of need.

Of the favelas, Ronaldo Lemos, director of the Center for Technology & Society at Rio de Janeiro State University, told Quartz, “by not being on the map, they (favelas) have very sad consequences in terms of public services. They don’t have an address, so they don’t get mail at the post office…You don’t get garbage collection, you don’t get electricity. That’s the reality for more than 1.5 million people in Rio.”

In Brazil’s largest newspaper (link in Portuguese), Lemos wrote of arguably less dire results: when Pokémon Go was initially released, the game’s creators used Google’s underlying mapping data, unintentionally excluding favela-dwellers from being able play. He insists, however, that what’s at stake is more than just a game.

“With new services, you don’t have access to whatever comes on top,” Lemos says. “Pokemon Go is a good example, but think about self-driving cars or drone delivery or anything that depends on maps. Uber, for instance, they will never have it. Anything that relies on maps, they are basically completely off the grid.”

“This is not a problem of Rio,” Lemos warns. “It’s a big problem that we have to solve at some point.”

In the meantime, if you’re looking to avoid Google’s reach, your options are the places where Google has yet to reach. Just be prepared to give up some conveniences along the way.