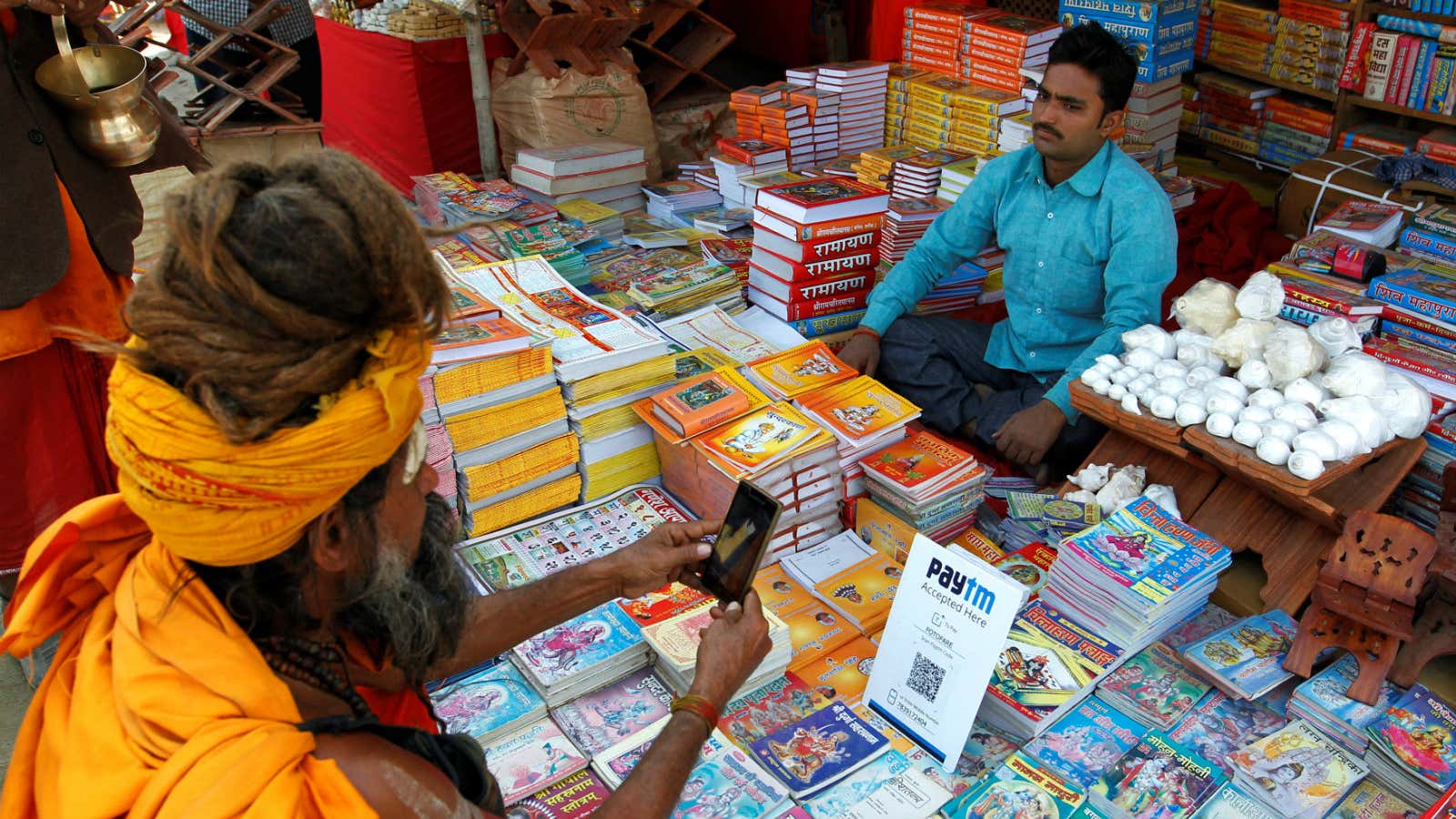

Narendra Modi wants Indians to stop using cash and go digital instead. A cashless economy is expected to increase transparency, clamp down on corruption, and boost the country’s GDP.

However, despite the brouhaha, Indians aren’t taking much to digital finance—use of electronic payments—a joint study by philanthropic investment firm Omidyar Network and Dalberg Global Development Advisors has found.

For one, although digital finance is said to be the next revolution in Asia’s third-largest economy, “adoption of this technology across consumer segments has been slow,” the study, released on May 18, says. ”What we found was that access does not automatically translate to usage. Many people aren’t actually using smartphones with data,” Smita Aggarwal, director, investments, Omidyar Network, said.

India is expected to have over 450 million smartphone users by June 2017. But, some 50% of them would not subscribe to data plans. Besides, less than 5% of rural adults own smartphones, according to Omidyar. A significant segment, particularly women, still don’t use smartphones, often due to conservative social norms, it noted.

The study is based on interviews of 384 persons at 30 locations across five states in October-December 2016. The idea was to go beyond macro numbers and understand consumer behaviour in the wake of digitisation, explained Aggarwal.

These findings would worry the government, banks, e-wallets, and startups rooting for a cashless economy. Digital finance is estimated to add some $700 billion to India’s GDP by 2025 and create 21 million jobs, according to consulting firm McKinsey. But if the Omidyar-Dalberg study is anything to go by, the picture is far from rosy.

Keep it simple

Rural Indians find it difficult to use digital services and apps. They lack the confidence to transact using a phone or a website, Aggarwal explained. There’s “a lack of ability to understand financial services due to heavy usage of jargon and content not found in the local colloquial language,” the report said.

In some cases, users couldn’t even differentiate between an account number and a PIN number, making them wary of using apps that require these. Then there are terms like “debiting” (when money is withdrawn from the account) and “crediting” (when money is deposited) that confuse them.

Given these issues, rural Indians naturally prefer local service providers like loan agents, self-help groups, micro-finance institutions, chit funds, savings associations, loans against gold, and private moneylenders, with whom they have long-established trust and comfort levels.

“The gold loan agent speaks politely and offers me water. He patiently explains the loan process. Also, I get the loan within a few minutes,” Mangai, a homemaker in a Karnataka village, said during one of the interviews.

A platform like BHIM-Aadhaar, tied to the government’s BHIM app, could be a solution as it does not require personal navigation or owning a phone. Anyone with the Aadhaar card and thumb-print can access BHIM at a merchant’s location. From its launch in December 2016 to facilitate cashless transactions to March 2017, BHIM had got 18 million downloads.

Challenges for women

The use of digital finance services by women is particularly low, the study found. Fewer than five out of 10 women in India own a mobile phone; females also form just 35% of mobile internet usage. Even otherwise, to most Indians, a smartphone is just a mode of entertainment and social media, raising fears that it will be a “bad influence and lead to sexual harassment or broken marriages,” the report said.

“Multiple men and women told us that newspaper articles and television news reported that social media usage by women leads to extramarital affairs and divorce,” the report said.

Men often don’t buy their wives, daughters or sisters smartphones. Many of the women who do use such handsets don’t have data connections.

“Girls shouldn’t be given mobile phones. It is not appropriate. Who knows who will they talk to? I haven’t given a phone to my girl. She is in high school, now let her get married,” a teacher in the Masia Bigha village in Bihar, told Omidyar.

However, if there are specific apps for expense management or education, usage among females could increase, the study shows.

For now, though, 1.3 billion Indians going fully digital with their money is still in the realm of fantasy.