The water has been inching closer to Rita Falgout’s house, lapping at the edges of her front yard. Her home is one of 29 in Isle de Jean Charles, a narrow island in the bayous of southeastern Louisiana that is slowly sinking into the Gulf of Mexico. The island, home to members of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw and the United Houma Nation tribes, is reached by a lone road that passes through the marshland with water on either side. Since 1955, the island has lost 98% of its land.

“Now there’s just a little strip of land left,” Falgout, 81, tells Quartz. “That’s all we have. There’s water all around us.” She’s one of just 100 people who lives in Isle de Jean Charles. Few outside know or care what’s going on there. “I’m anxious to go,” she says.

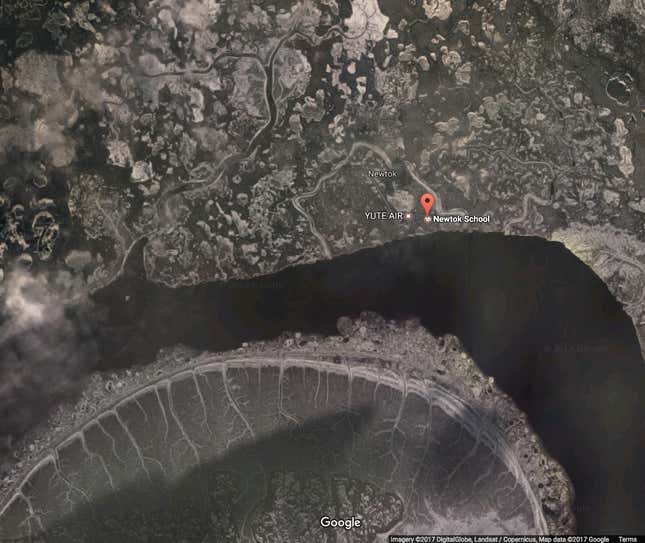

On the other side of the US, a small village of approximately 350 people on the Ninglick river on the western edge of Alaska faces similar troubles ahead. In Newtok, rising seas and melting permafrost caused by climate change have meant the Ninglick is gradually eroding the land. “They see the river bearing down on them. They all accept it, they all know they have to leave,” said Joel Neimeyer, the co-chair of the Denali Commission, a federal agency tasked with coordinating government assistance for coastal resilience in Alaska. “The river is coming at 70 feet a year. You can just take out a tape measure and measure it.”

Both towns were left with an awful choice that is going to come to many who live in coastal areas across the US that are at risk of being inundated as the sea level continues to rise: Move or perish. But then they heard of an unusual, first-of-its-kind competition held by the Obama administration, which offered the chance for relocation. The National Disaster Resilience Competition (NDRC) was organized by the federal government and aimed to help communities and states recover from previous disasters and reduce future risks.

For both Isle de Jean Charles and Newtok, the competition offered hope. It also suggested that powerful people far away cared. US president Barack Obama visited Alaska in September 2015, a few months before the Paris climate summit that would create a landmark comprehensive global climate deal, and said, “What’s happening in Alaska isn’t just a preview to what will happen to the rest of us if we don’t take action, it’s our wake-up call. The alarm bells are ringing.”

As climate change impacts larger swathes of US coastal towns, the idea of climate-induced migration is no longer an abstract concept that is only impacting far-away islands in the Pacific. A March 2016 study (pdf) suggests that a 6-foot (1.8-meter) rise in sea levels by 2100, fuelled by a collapse of the polar ice caps, could lead to 13.1 million Americans along the coasts losing their homes to the rising tide. Even a more modest rise of 3 feet would leave 4 million homeless.

With the US population highly concentrated in dense coastal areas, this raises urgent questions for the government. Where would you move everyone? How do you move entire towns and cities? Who will pay for it? And, perhaps most contentiously, who do you help first?

The perfect community

Obama’s disaster competition came about in unusual circumstances. After Hurricane Sandy struck the US East Coast in 2013, Congress passed a bill awarding $16 billion in long-term recovery grants to the department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The money awarded to HUD was earmarked for Hurricane Sandy and other eligible disasters that took place between 2011 and 2013.

Setting up disaster recovery as a competition ensured that the department funded creative, forward-looking solutions for rebuilding infrastructure, says Marion McFadden, who was then the deputy assistant secretary for grant programs at HUD and oversaw the competition. The department had had a good experience with Rebuild By Design in 2013 with a competition that brought together teams of designers, architects, engineers, ecologists, and hydrologists to come up with solutions to improve resilience in areas hit by Sandy. So after a bulk of the money was set aside for rebuilding after Sandy, HUD set aside $1 billion and announced the competition in October 2014. “We wanted to ensure that we weren’t putting problems back with the money we sent in and were really looking for innovation,” McFadden says.

The competition was run in two stages. All states and local governments that had experienced a presidentially declared major disaster between 2011 and 2013 or had received disaster recovery funding from HUD were invited to apply. This included 48 states, plus Puerto Rico, Washington, DC, and several local governments. The process of the application was gruelling, and with all the different inputs required, a bureaucratic nightmare.

Relocating entire towns and villages was not the goal of the competition—you could present any solution—but Newtok saw its opportunity. In Alaska, a team of five people from four different government agencies formed the core team for the application. Moving wasn’t a new idea. Back in 1984, when the local government noticed that the city was losing ground and requested an assessment of the erosion issue, consulting geologists found that attempting to stop the erosion would be extremely expensive. “Relocating Newtok would likely be less expensive than trying to hold back the Ninglick River,” they said in a letter (pdf) to then mayor John Charles. Yet it took the community nearly 10 years to decide what to do. In 1996, they finally voted to move.

In selecting a place to move, the community had to ensure they preserved their livelihood. The village of about 350 members of the Yupik tribe relies mostly on a subsistence economy of fishing, hunting moose, muskox, and birds, collecting bird eggs, and gathering berries and greens. The community identified Mertarvik, a piece of land within their subsistence area, which would work for them.

But the land was a protected wildlife refuge and the community began a seven-year process of negotiating with the US Fish and Wildlife Service. By 2003, they finally owned the title to Mertarvik, about 10 miles south of Newtok. In the years since, the local community and the state has struggled to find the funds to develop this new land. “No funding agencies were willing to invest in this new place where there was no population,” says Sally Russell Cox, a planner with Alaska’s Department of Commerce, Community, and Economic Development.

So when officials in the state of Alaska heard about the National Disaster Resilience Competition in 2014, they felt like Newtok would be well placed to win some much-deserved funding. “It seemed like this community that was going through this active relocation process would be a perfect community to be applying for funding for,” says Cox, who was part of the team that developed the state’s application for the competition.

Meanwhile, in Louisiana, the strip of land of Isle De Jean Charles was fast being eaten up by the sea and regular floods and hurricanes had helped to show the community that resettlement was their only available option. They seemed a good candidate for the grant because, unlike other places, the residents of the village did not have to be convinced of the need to resettle.

“One of the hardest things about this is for people to decide to leave the place where they’ve grown up,” says Pat Forbes, the executive director of the state’s Office of Community Development, the agency in charge of administering the federal climate grant. “Having a community that had already been considering that and coming to grips with it for a while was an advantage.”

Mathew Sanders, then a policy advisor to the state, was having sleepless nights over the application. There were about 15 people from various parts of the state government working on the application, with another 15 people brought in from the private sector to provide expertise. “We were working across the large geographic area in a fairly short period of time and trying to really put together a series of high-minded ideas and also drill down with some specificity,” said Sanders. “It was extremely difficult.”

After the initial applications were reviewed, 40 top-scoring state and local governments were selected to go on to the next phase in June 2015, where applicants had four months to refine their plans for implementation. Both Isle De Jean Charles and Newtok made it to the second round.

‘Simply a backdrop on your way to Paris’

Alaska and Louisiana took very different approaches to arguing their case for funding. The state of Alaska argued that the projects they were proposing were in the places that had the greatest and most urgent need (pdf). “There’s a huge reduction in arctic sea ice which has in the past provided a buffer for communities on the coast from storms,” said Cox. “The science all bears it out. Those are the types of facts that we provided to build a case that we are feeling the impacts of warming up here a lot earlier than other places are. It’s affecting very vulnerable communities.”

Alaska decided to apply for funding for projects in four different communities, one of which was the relocation of Newtok. The four projects had a combined request of $286 million (pdf), of which $69 million (pdf) was earmarked for Newtok. The final proposal included costs for creating housing in Mertarvik, developing a road system and community landfill, and demolishing the abandoned homes in Newtok.

In Louisiana, the team felt that the federal government was not simply looking to solve current problems but also to create a model for future projects. “What they were looking for was projects that could be duplicated and replicated not only in Louisiana but around the country in response to threats to communities,” Forbes says. And so they presented the Isle De Jean Charles relocation plan as an experiment, a novel solution in a place which was experiencing coastal land loss and sea level rise problems which would impact other US coastal areas in the future.

“If we’re going to try and figure out how to try to solve this problem anywhere, we presented ourselves as a test case, and as a laboratory,” said Sanders. “We were mindful of the fact that the land loss and sea level rise conditions that we’re facing here in Louisiana, we expect to see replicated in other places across the Gulf coast and up the Eastern Seaboard. If we’re that proverbial canary in a coalmine, we thought it was a fairly natural fit for HUD to make these types of investments here to begin to try to build those models and test concepts that could be scaled and replicated in other places.”

In January 2016, HUD announced the winners of the competition. Louisiana received $92.6 million, of which $48 million was to go towards relocating the people of Isle de Jean Charles to higher ground. “What set Louisiana’s relocation application apart was the dedicated resources for studying and evaluating the process of relocation,” said McFadden, who was then working at HUD and oversaw the competition. “We didn’t really have a good database to draw on of experiences and lessons learned from communities moving.”

Not everyone was so lucky.

In a letter to the state of Alaska denying its application for funding, HUD noted that applicants had requested over $7 billion in funding, when only $1 billion was available. Senator Lisa Murkowski wrote in a letter to Obama that said, given his public statements acknowledging the impact of climate change on coastal Alaskan villages, the fact that Alaska did not get any funding “left rural Alaskans looking like simply a backdrop on your pathway to Paris.”

The state of Alaska asked for a briefing with HUD to discuss the results of the application. At the meeting, representatives of HUD talked through the criteria of the application and where Alaska had lost out. Mark Romick, the deputy executive director at the Alaska Housing Finance Corporation, who was part of the team that put together the application and was in the room, described the conversation as “not wholly satisfying.” “Need wasn’t a big factor,” said Romnick of his conversations with HUD. “It was how you responded to the goal of resiliency.”

Alaska was also disadvantaged because the competition’s metrics gave a lot of weight to population; the communities that are most impacted in the state are sparsely populated and very spread out. While Isle De Jean Charles is a very small settlement, the scoring took into account that the state of Louisiana overall is more densely populated. Alaska’s application was penalized as its investment of nearly $20 million over the years in Newtok’s relocation efforts and development of the new site did not qualify under HUD’s definition of “leverage.” Cox was surprised by the outcome. “There hasn’t been a funding opportunity like this and so, yes, this was very disappointing,” she says.

Even McFadden, who ran the competition, said that the process could be “frustrating” and emphasized the technical nature of bidding for government money. “You can have a great idea that isn’t fleshed out very well and doesn’t score as highly as it could, and a more technically proficient application that’s not as ambitious,” she says. “It doesn’t mean the quality of the idea—it’s just the way it’s laid out on paper.”

Isle de Jean Charles was the only town to receive funding for relocation; the bulk of the rest of the funding went towards building coastal resilience in other states and towns. For example, HUD awarded (pdf) the state of California $70.4 million to build resilience against wildfires, New Orleans $141 million to establish a Resilience District in the Gentilly neighbourhood, and gave New York City $176 million to build a coastal flood protection system. Florida, which has 1,350 miles (2,170 km) of coastline, had five towns that applied for NDRC aid; it did not make it through to the second round (pdf).

In Florida, one in eight homes—or about 934,000 existing properties worth over $400 billion in current housing value—could be underwater by 2100, according to projections by Zillow. Philip Stoddard, the mayor of South Miami, thinks that residents should not wait for the federal government to bail them out. “The idea that the feds are going to buy people out has already failed. It’s not happening nearly at the rate that it needs to happen,” Stoddard tells Quartz. “There’s just nowhere near enough money. Maybe a few lucky people will get help, but it’s going to be a shrinking minority.”

By choosing to fund the Isle De Jean Charles resettlement, the federal government has already made it clear that, in some circumstances, it supports relocation. The question of when it’s willing to step in—and how often—is still open.

How do you move a sense of belonging?

With the funding in hand, Isle de Jean Charles is now navigating the challenges of moving an entire town. They have narrowed the list of possible relocation sites down to three candidates based on their future flood risk profile. They are hoping to build consensus within the community to move forward with one those sites in the next two months and then begin the lengthy process of acquiring the land.

“There’s no real blue-print or playbook for us to work from,” said Sanders. Each week, about 20 people dial in to a conference call where the state officials speak with community members. Part of his job, says Sanders, is simply to reassure the local community that this plan will work. The people of Isle De Jean Charles have been waiting a long time and have already experienced a few aborted starts, making them wary of federal aid.

“Everytime I talk to the people down there there is some idea that the money is going to go away for some reason,” says Sanders. “I try to calm nerves and help people understand that we’re not going to take this money and go do other things with it.”

They are enlisting a planning team to figure out what the new community will look like and an “exit strategy” from the town’s current location as the island slowly disappears. They hope to begin construction by 2018. With another hurricane season around the corner, they are creating a transitional housing program so that people can move into rental units if the town is hit by a disaster in the interim. The deadline for spending their federal funds is September 2022; the state of Louisiana is hoping to resettle the community by then.

But identifying climate risks and coordinating logistics is only one aspect of planned relocation. In selecting a site for relocation, experts argue, planners need to consider whether the community has the right skill sets to find work in their new environment. “The worst thing to do would be just to relocate a population into a place that’s already struggling economically and has an extremely different set of industries,” Kate Gordon, the founding director of the Risky Business Project, which examines the economic risks presented by climate change, tells Quartz. “If you are relocating a population that just doesn’t have a match in terms of skills and culture—I think that would probably be disastrous.”

In the case of Isle De Jean Charles, which is largely inhabited by tribal communities, state officials were faced with the question of transporting a unique culture, intact, to another place. Louisiana state officials are attempting to understand the community’s culture and ensure that it is “embedded” in the blueprint for the new settlement.

The psychological impact of displacement, even when the community knows that it is in their best interest, is potentially devastating.

“Although the destination could be just 5 miles away, people need time to understand that their lives and all the memories they have related to that place will just remain memories because they will have to settle in some other place,” said Cosmin Corendea, associate academic officer at United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security, who specializes in creating legal frameworks to protect and promote the rights of people displaced by climate change. He believes that one of the reasons the Isle De Jean Charles resettlement will be successful is that people had years to come to terms with the move.

Officials all over the country are closely watching the current efforts to see how it pans out. “What comes out of the Isle De Jean Charles relocation effort may well inform what the federal government thinks it can do,” said Mark Davis, director of the Tulane Institute on Water Resources Law and Policy. “I mean, heavens, if you can’t move 50 people, how do you move 100,000? And if you do successfully move 50, what does that tell you might be possible elsewhere?”

In Newtok, as the shock of losing out wears off, state officials in Alaska are hoping to continue the village’s relocation efforts. There are plans for roads to be built over the summer and a few more homes to be constructed at the new site, but funding remains a challenge. Building a single energy efficient home in rural Alaska costs about $300,000, said Cox. Then there is water, sanitation, sewage, a school, a store, and an airport; each fall under a different government agency.

But with the Trump administration pulling of the Paris climate accord that Obama used Alaskans to champion, federal funding for Newtok seems unlikely to come anytime soon. It’s unlikely that Trump’s HUD would approve of such a competition again anytime soon—even as towns like Newtok, and and island nations like Tuvalu, are struggling to deal with rising seas now. For the world, what these residents are facing is only the beginning. “No nation, whether large or small, rich or poor, will be immune from the impacts of climate change,” Obama himself warned recently.

Newtok’s only school is a battered structure with peeling blue and white paint on its wooden boards propped up on stilts. It sits at the village’s highest point, its sole source of running water, and serves as a community center—and it’s also only a few hundred feet from the Ninglick River. At the current rate of erosion, the river could reach the school’s site this year.

“My observation in the country is that there hasn’t really been a comprehension of how this changing climate is going to impact the built environment over the years,” Neimeyer says. “Eventually, I think this country will get there.”

This article was updated on Aug. 24 to reflect appropriate attribution to Julie Dermansky for her photos.