On the bright side, your suspicion that the world is ending is making you a better parent, partner, and friend

Yes, there is a lot to worry about. There’s the threat of nuclear warfare and insecurity about climate change and the fact that the US nuclear defense system is based on islands threatened by rising sea levels.

Yes, there is a lot to worry about. There’s the threat of nuclear warfare and insecurity about climate change and the fact that the US nuclear defense system is based on islands threatened by rising sea levels.

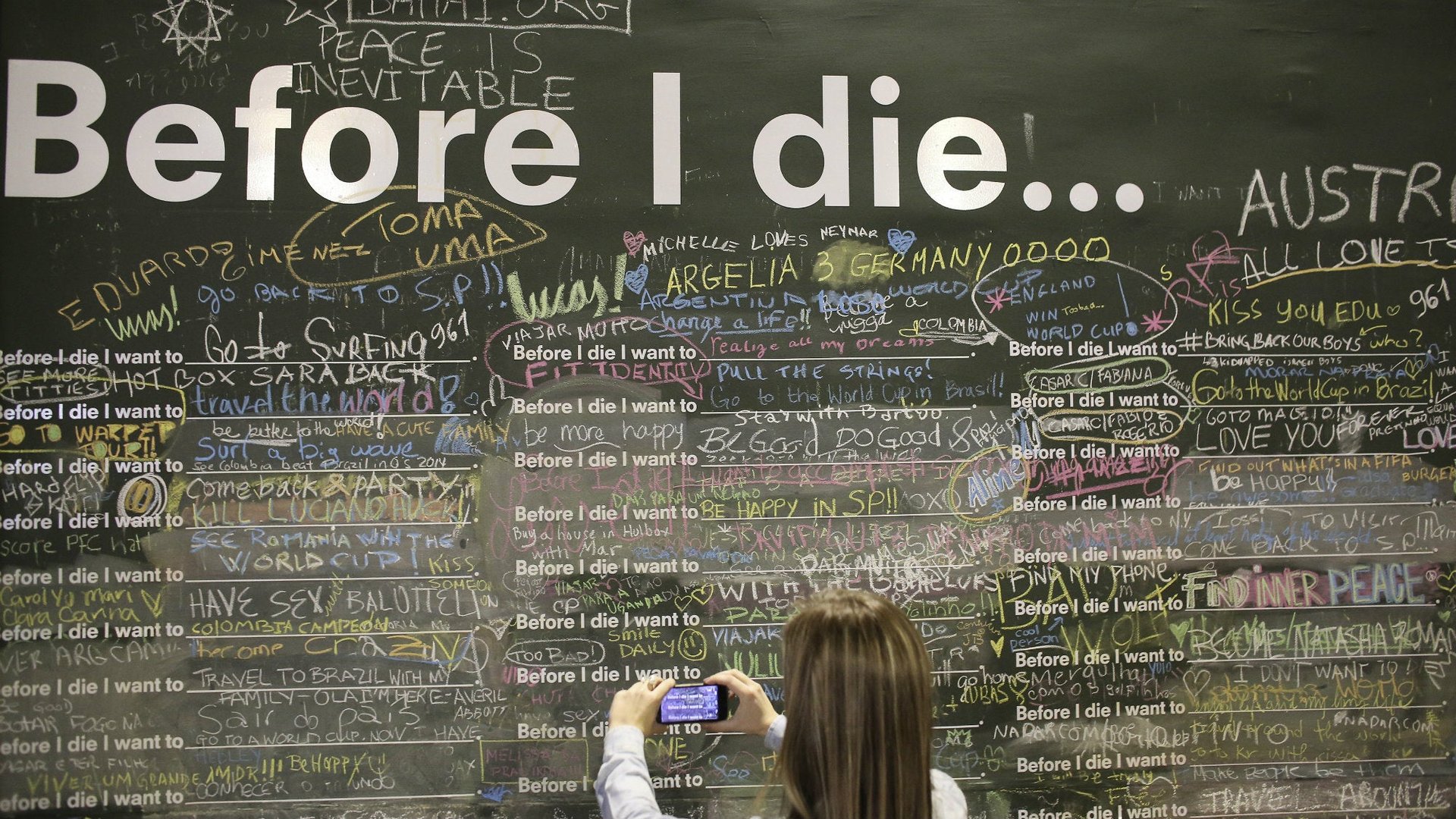

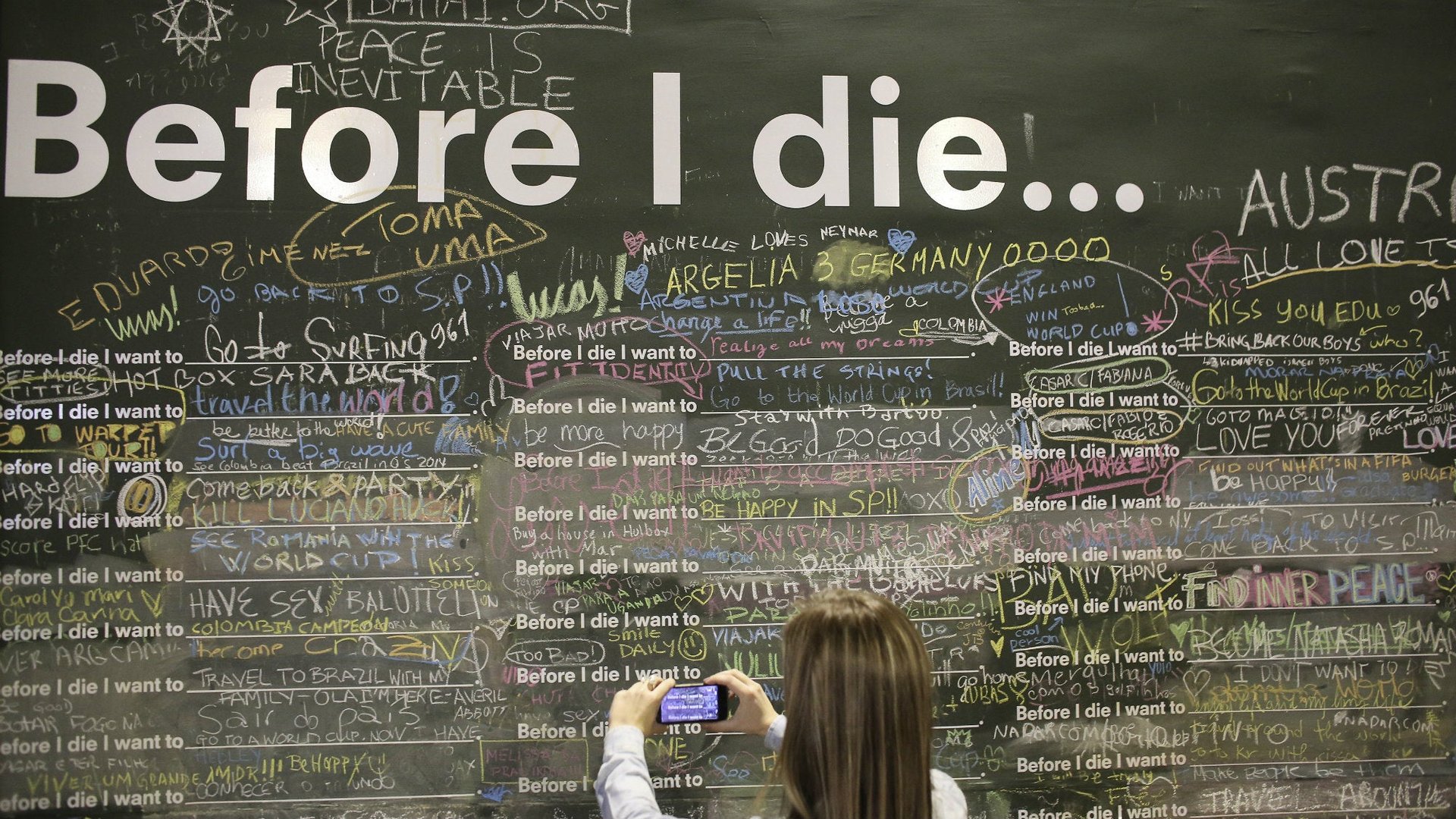

In the face of existential threats over which you exert very little control, you may find yourself holding loved ones closer. Making time to call an old friend. Setting aside the phone with the utterly terrifying Twitter feed to be fully, genuinely present with your children or partner.

It’s not just you. When we start to think we have less time to live—whether that’s due to age, illness, or external threats—we make adjustments (often subconsciously) to the way we live now. In research on subjects old and young, healthy and ill, in stable political climates and not, Stanford University psychologist Laura Carstensen has observed consistent correlations between how we spend our time and how much time we believe we have to spend.

When time seems abundant, we seek new experiences and new friends, and delay immediate pleasures for work and education we think will pay off in the future. As the physician Atul Gawande summarized the theory in his book Being Mortal:

When horizons are measured in decades, which might as well be infinity to human beings, you most desire all that stuff at the top of Maslow’s pyramid—achievement, creativity, and other attributes of “self-actualization.” But as your horizons contract—when you see the future ahead of you as a finite and uncertain—your focus shifts to the here and now, to everyday pleasures and the people closest to you.

In one experiment, Carstensen studied men aged 23 to 66—some healthy, and some with advanced HIV/AIDS. Asked to value hypothetical time spent with people ranging from family members to famous authors, younger, healthier people rated new connections higher. Older people placed more value on time with close friends and family. So did the terminally ill.

The test was repeated with another group of subjects ranging from children to the very elderly. The same pattern emerged—though when asked to imagine they were moving far away, young people made the same choices as old people.

Geopolitical events can trigger existential awareness too. Carstensen’s team surveyed populations in Hong Kong in the anxiety-filled times before the handover to China in 1997 and during the SARS epidemic of the early 2000s, and in the US after the 9/11 attacks. In both cases, when the future felt uncertain and potentially life-threatening, people preferred sticking with tighter social networks and investing time in those they loved. When things calmed down, their choices returned to the expected distribution based on age.

It’s long been observed that older people report higher levels of contentment than younger people. Carstensen argues that it’s not simply the extra years that bring appreciation of those closest to us, but the growing awareness of our mortality. If there’s any comfort in the news these days, it’s that fear of the future can help you live in the present.