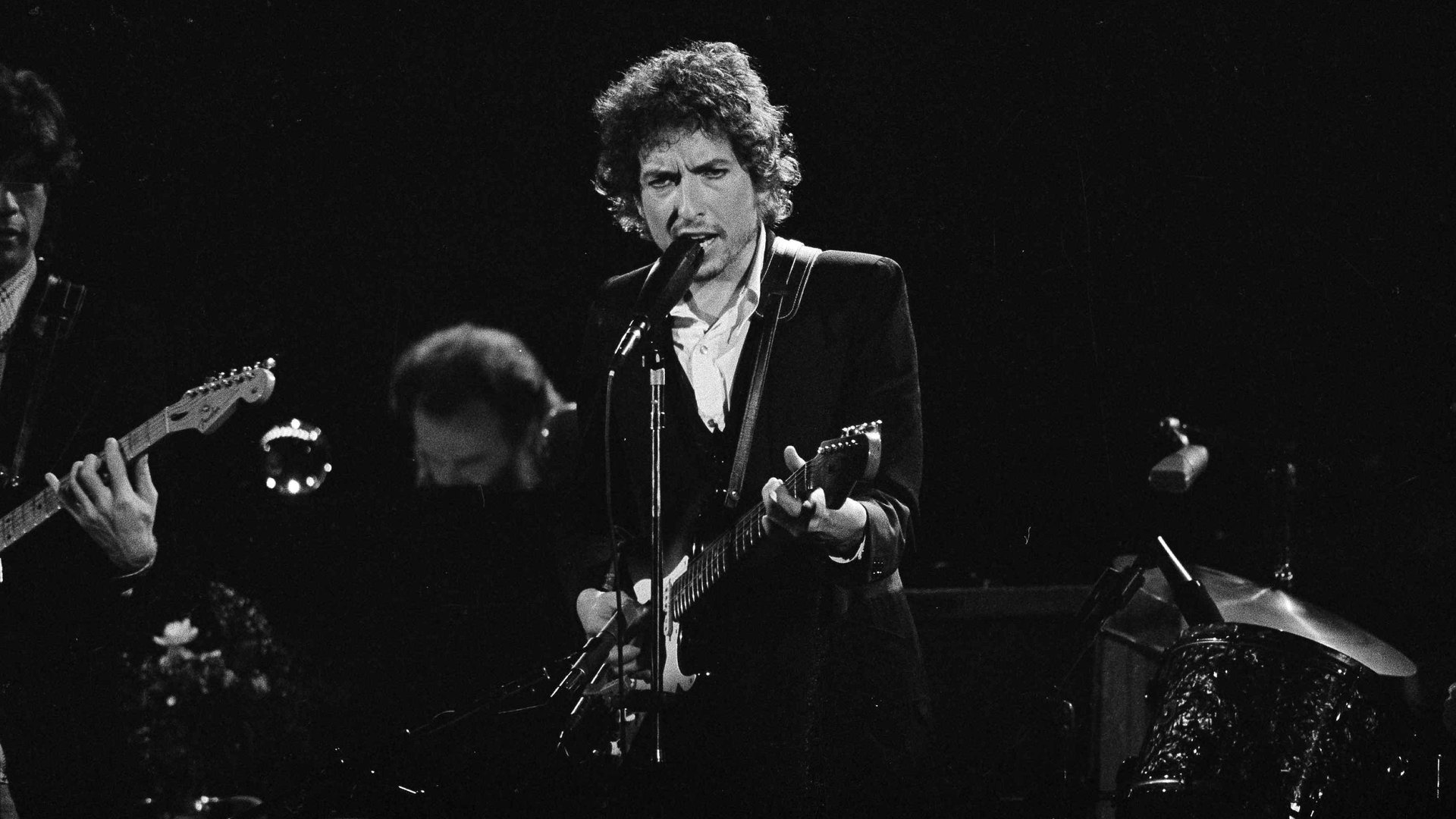

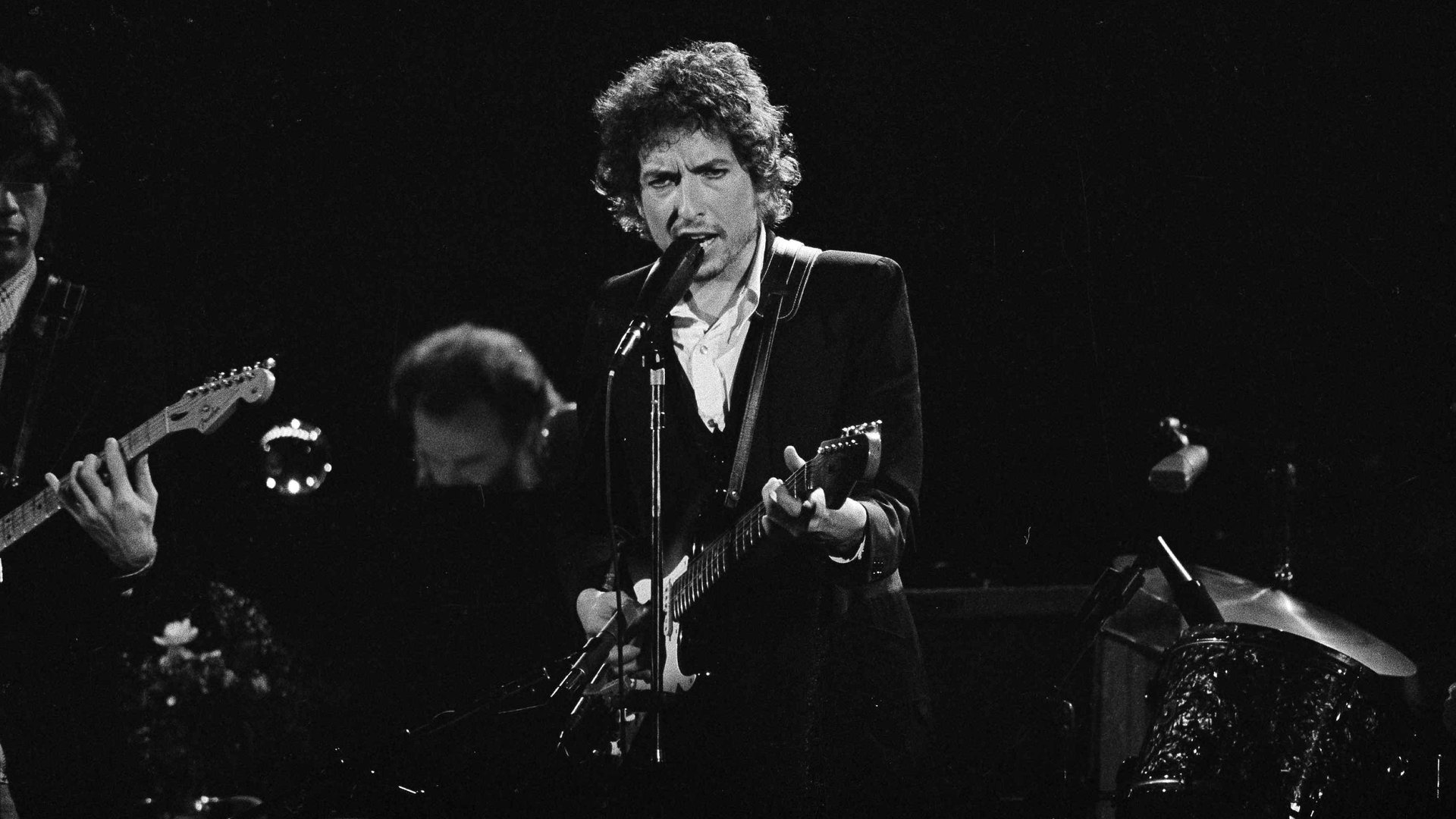

At the very last minute, Bob Dylan earned his Nobel prize money with this speech

Last December, the recipients of the 2016 Nobel prizes gathered in Oslo and Stockholm to receive their awards and give lectures in their fields of expertise. Bob Dylan, the notoriously reticent American musician who unexpectedly won the prize in literature, was, expectedly, not among them.

Last December, the recipients of the 2016 Nobel prizes gathered in Oslo and Stockholm to receive their awards and give lectures in their fields of expertise. Bob Dylan, the notoriously reticent American musician who unexpectedly won the prize in literature, was, expectedly, not among them.

From the moment the folk singer was announced as the winner in October he bucked prize formalities: He was silent for a full two weeks about winning the award, ignoring calls from the academy; he didn’t attend the ceremony where he’d normally collect the prize, and sent in his acceptance speech instead; he picked up the award four months later in a private ceremony when it was convenient—he happened to be on a European tour at the time.

But the prize stipulates that winners must give a lecture by June 10, six months after the prize ceremony, to be eligible for the cash prize. And Dylan has slid in just in time. He recorded a lecture on June 4 in Los Angeles to meet the prize requirements and to get his 8 million Swedish kronor (about $924,000). Today the foundation released a video on YouTube, a 27-minute audio recording of Dylan’s voice reading the lecture, set to some discordant piano.

Dylan focuses on three works that have inspired him: Moby Dick by Herman Melville, All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque, and The Odyssey by Homer. It’s like watching the coolest kid in your English class, after not speaking for the entire semester, get up in front of everyone and give an impromptu, poetic, somewhat opaque book report from memory.

Moby Dick

Dylan admires Melville’s poetic quotability, he says, and the sheer drama of the huge novel about a man obsessed:

Whale oil is used to anoint the kings. History of the whale, phrenology, classical philosophy, pseudo-scientific theories, justification for discrimination—everything thrown in and none of it hardly rational. Highbrow, lowbrow, chasing illusion, chasing death, the great white whale, white as polar bear, white as a white man, the emperor, the nemesis, the embodiment of evil.

All Quiet on the Western Front

Dylan says he felt swept up in the World War I novel’s message of incomprehensible chaos. “This is a book where you lose your childhood, your faith in a meaningful world, and your concern for individuals,” he says. “You’re stuck in a nightmare.”

He stays in a second-person address to describe the feeling of being overwhelmed by merciless, relentless terror:

You’re so alone. Then a piece of shrapnel hits the side of your head and you’re dead.You’ve been ruled out, crossed out. You’ve been exterminated. I put this book down and closed it up. I never wanted to read another war novel again, and I never did.

The Odyssey

Dylan talks about being drawn to Odysseus’ wanderings and missteps, as well as the treachery of the world around the legendary hero:

Goddesses and gods protect him, but some others want to kill him. He changes identities. He’s exhausted. He falls asleep, and he’s woken up by the sound of laughter. He tells his story to strangers. He’s been gone twenty years. He was carried off somewhere and left there. Drugs have been dropped into his wine. It’s been a hard road to travel.

Dylan concludes that literature has influenced him, in conscious and subconscious ways, and says you don’t necessarily need to get it all to get something out of a book, or poem, or song. “If a song moves you, that’s all that’s important,” he says. “I don’t have to know what a song means. I’ve written all kinds of things into my songs. And I’m not going to worry about it—what it all means.”