China’s ignorance about its own maps created a false history of its ancient role in South Africa

In 2002, the South African parliament hosted an exhibition as part of the “Parliamentary Millennium Project” held in Cape Town. Launched by Dr Frene Ginwala, former speaker of parliament, the project was designed “to contrast European perspectives with indigenous ones,” and “promote the recognition of shared South African identities.”

In 2002, the South African parliament hosted an exhibition as part of the “Parliamentary Millennium Project” held in Cape Town. Launched by Dr Frene Ginwala, former speaker of parliament, the project was designed “to contrast European perspectives with indigenous ones,” and “promote the recognition of shared South African identities.”

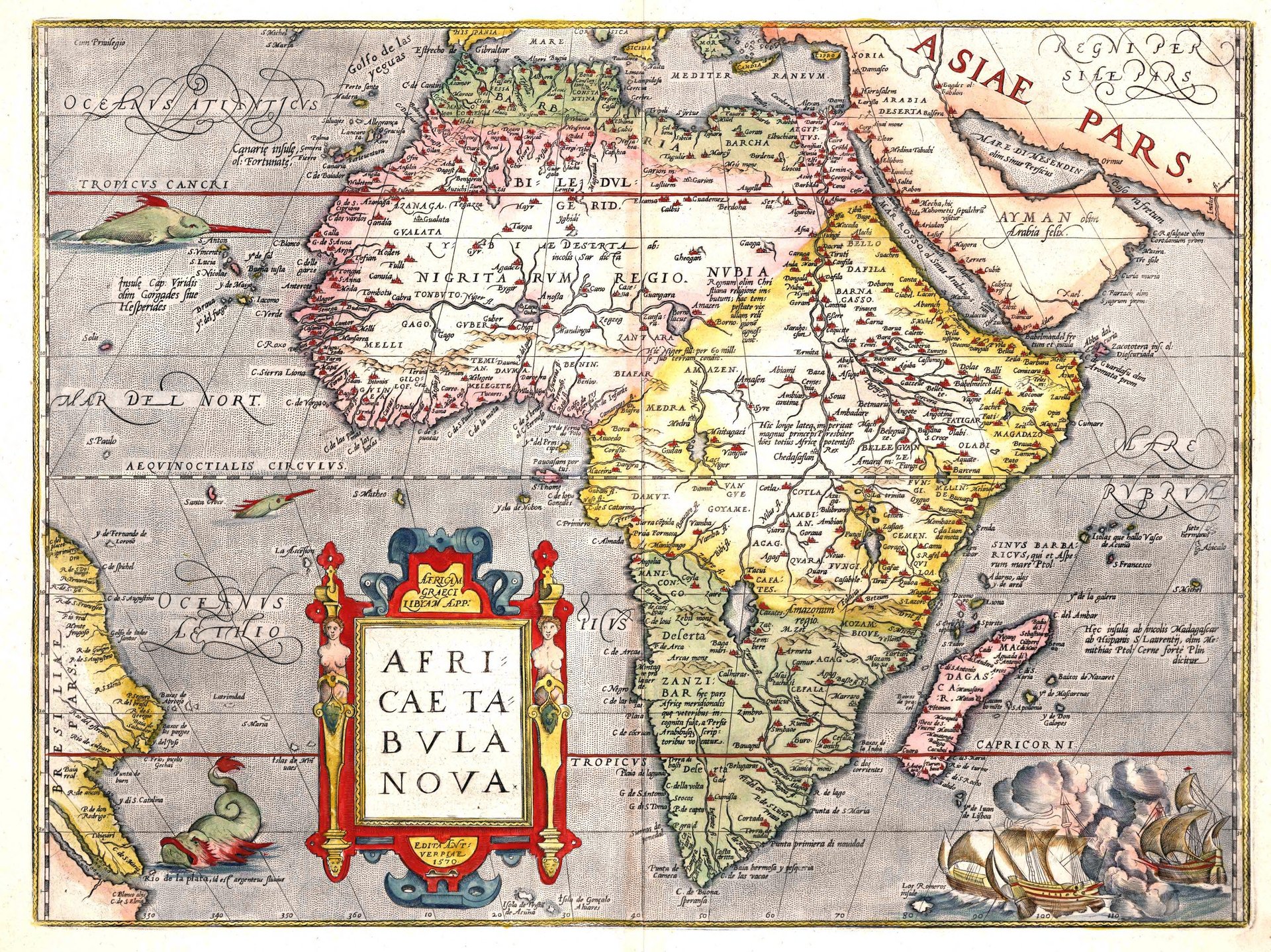

At the centerpiece of the event was a map gifted to South Africa by the People’s Republic of China. The “Da Ming Hunyi Tu” is an amalgamated illustration of the Great Ming empire. The bottom of the map shows an early depiction of an east African coast (now present-day Tanzania).

The “Da Ming Hunyi Tu” at the exhibition was a 1402 Korean copy of the original, estimated to date back to 1389. Much fanfare was made about the possibilities of Chinese presence on the continent prior to the arrival of Europeans. Liu Guijin, China’s former ambassador for African Affairs, stated in a Q&A on the embassy’s website that the map proved that “friendly exchanges between China and Africa” went “back to ancient times.” He used admiral Zheng He’s expeditions along the east African coast (now Somalia and Kenya) as an example of a “time-honored” and “friendly” relationship between China and Africa.

But according to cartographer, Alexander Akin, the idea of age-old Sino-African relations is based on a conflation of historical facts related to the “Da Ming.” In his paper, “The Da Ming Hunyi Tu: Repurposing a Ming Map for Sino-African Diplomacy,” he argues that the depiction of an east African coast most likely derives from Middle Eastern observations of the continent. He lays out two possible origins of the map. The one cites the work of Japanese cartographic historian, Takahashi Tadashi. In 1963, Tadashi published “Eastward diffusion of Islamic world maps in the medieval era.” In it, he speculated that the “Da Ming” was based on the description of a globe given to Mongol ruler, Kublai Khan, by Persian astronomer, Jamal ad-Din in 1267. The other source is the sailing guides taken from Muslim mariners by the Yuan government in 1287.

“Traders from the Middle East were certainly moving between northeastern Africa and China well over 1,200 years ago,” says Akin in an email. In terms of trade and diplomacy, he said “a small number of African slaves” were “imported from Zanzibar to the court” during the Tang dynasty (618 – 907 CE).

For people who haven’t studied advanced Chinese history, Akin said it’d be easy “to assume that a Chinese map that depicts Africa in the Ming dynasty must have something to do with [Zheng He’s] missions.” He also attributed “historical ignorance” and “Sinocentric assumptions (the Chinese equivalent of Eurocentrism)”for the misrepresentation of the “Da Ming” as evidence of early Sino-African exchanges.

While China’s ignorance may have been the result of cultural bias and human error, the repurposing of the “Da Ming” helped calm anxieties about growing Chinese presence in South Africa. After years of condescension and prejudice soon after the end of Apartheid, South Africa has since come to embrace Chinese investment in the country, as citizens remain uncertain of what to make of China in the midst of an unsteady economy, the Gupta leaks, and a British PR company stoking racial tensions.

The “Da Ming Hunyi Tu” enabled China to play to the anti-imperialist and pan-African sentiments in the country. By leaning on its support of struggle organizations such as the Pan Africanist Congress and African National Congress (while being oblivious of the African slaves brought to China during the Tang dynasty), the country was able to reassure South Africans that unlike Europe, its relations with Africa would be defined by mutual benefit and comradeship.