Social media helped but it isn’t ready yet to deliver political change in Kenya

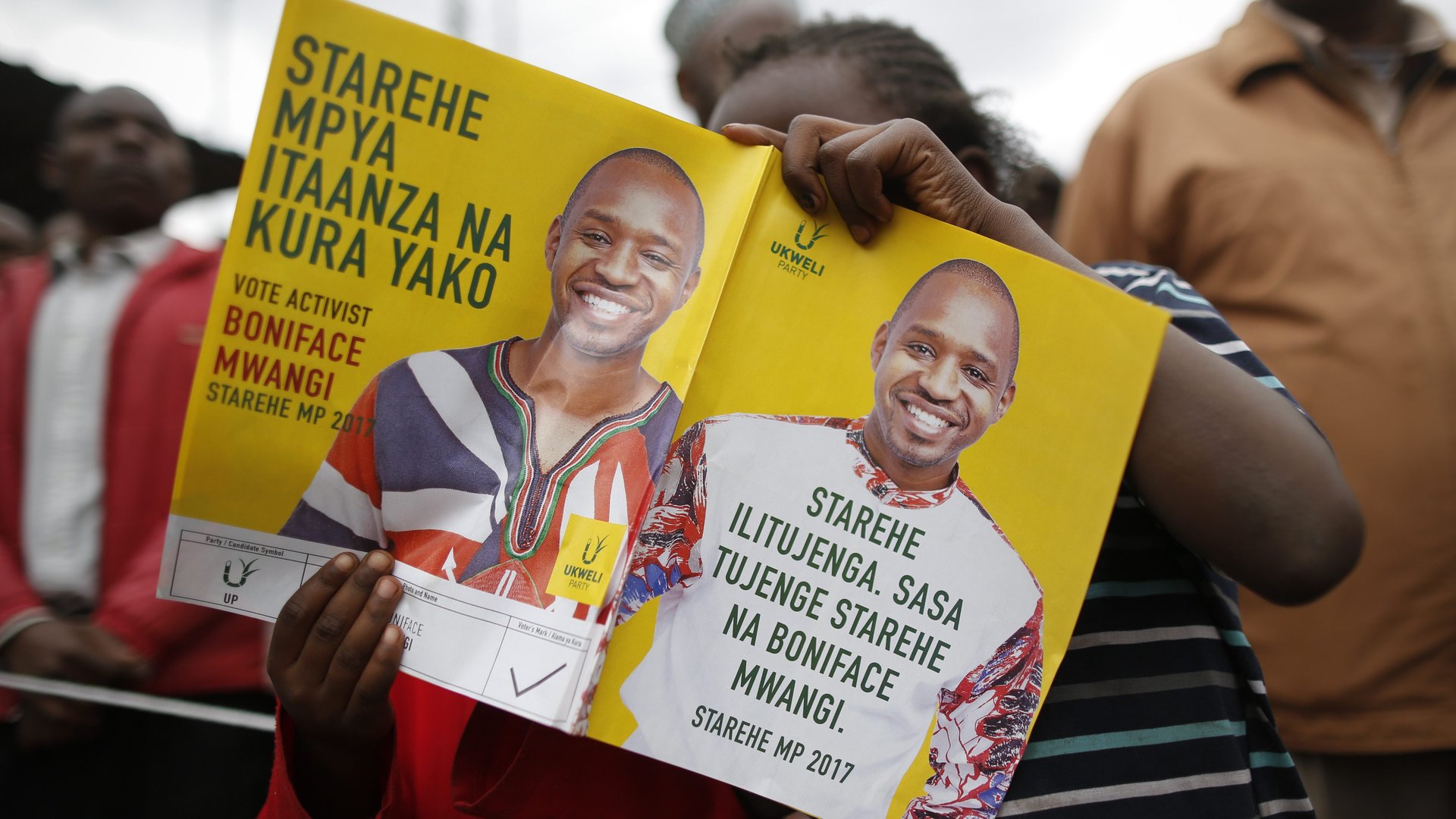

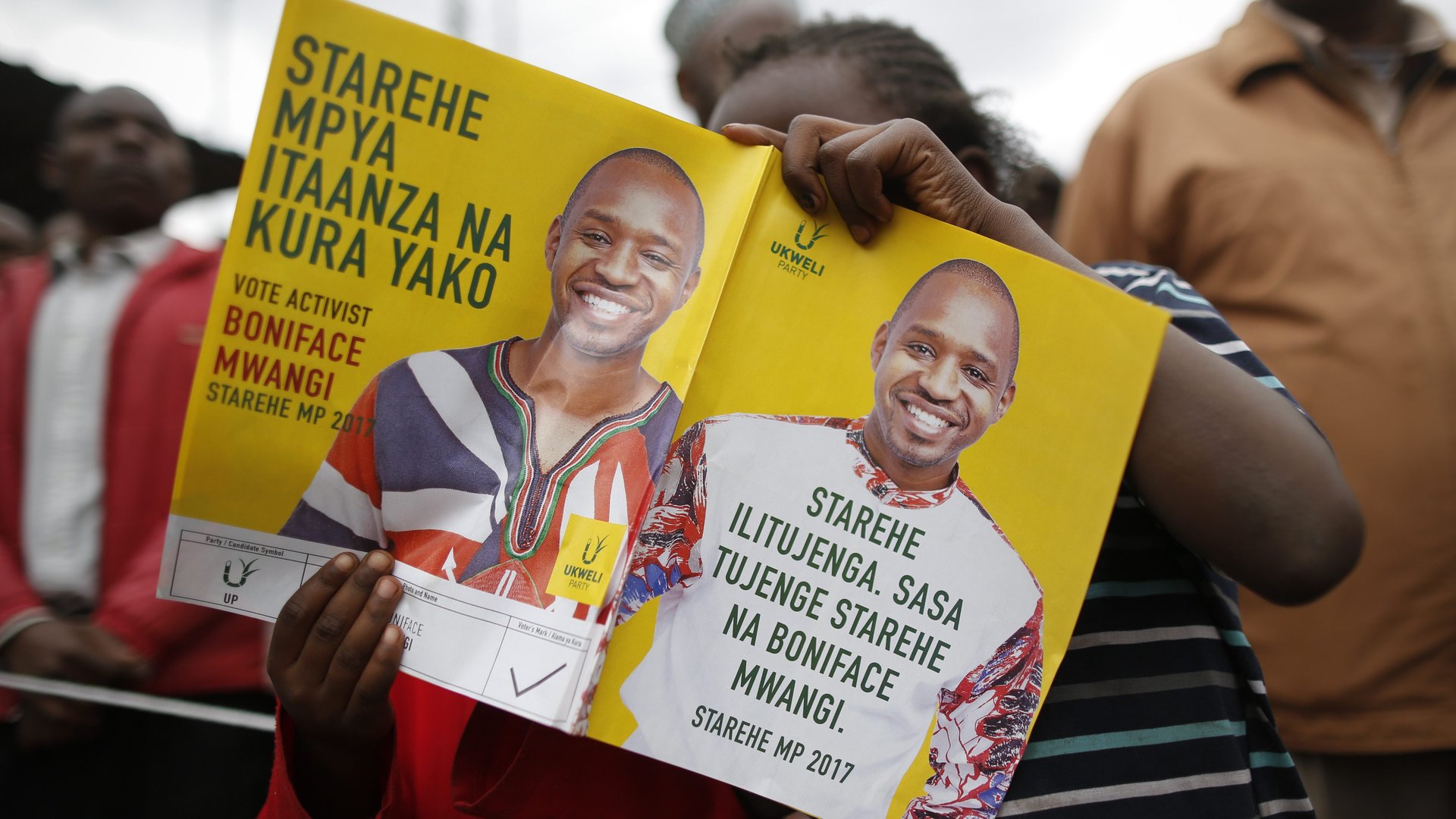

On Aug. 12, two days after conceding defeat for losing the parliamentary seat of Starehe Constituency in the capital Nairobi, Boniface Mwangi urged his supporters to come out one more time. Mwangi, a photojournalist turned political activist turned candidate asked his followers to assemble at his campaign headquarters and help remove his posters from around the city.

On Aug. 12, two days after conceding defeat for losing the parliamentary seat of Starehe Constituency in the capital Nairobi, Boniface Mwangi urged his supporters to come out one more time. Mwangi, a photojournalist turned political activist turned candidate asked his followers to assemble at his campaign headquarters and help remove his posters from around the city.

“By next week, all my posters will be down,” Mwangi promised in a tweet.

Like much of the traditional messaging surrounding the campaign, posters, billboards, and television ads were a mainstay in the Kenyan electioneering season. And just like some other politicians, Mwangi conducted an elaborate door-to-door campaign asking voters to come out in large numbers and elect him.

But the 34-year-old also topped all that by deftly employing social media, engaging his critics, and galvanizing a young electorate. It’s something future candidates, especially young independents and newcomers will use as a case study in elections to come.

While many traditional candidates have used social media like Mwangi, he presented himself to be adroit at utilizing social media in a way never seen before in Kenyan politics. Mwangi was able to take advantage of his huge reach on Twitter (741,000), Facebook (271,000), and Instagram (60,000) to canvass for support, send out a weekly newsletter via email and WhatsApp about his events, raise thousands of dollars in funds, and swell his base of followers.

A first-time candidate without the prestige or the backing of a major political party, Mwangi organized young people to register at his constituency to vote for him, and then solicited their support to volunteer for his campaign and help mobilize resources.

Mark Kaigwa, a communications specialist and the founder of tech research company Nendo, says Mwangi and his team broke a new ground on how politicians connect with an increasingly digitally-savvy electorate in Kenya. “They are a model case,” Kaigwa said.

On Aug. 8, more than 15 million Kenyans voted in a tightly-contested general election that saw president Uhuru Kenyatta beat his rival, Raila Odinga. In many ways, the election was fought across social media platforms, with both the government and the opposition using various tools to pitch their policies, provide spin, and shape their images. Fake news, which became a mainstay of the campaign, was peddled on WhatsApp; attack ads were widely shared on YouTube and Instagram, and political parties used Facebook Live and Periscope to engage voters.

Kaigwa says the 2017 engagement on social networking sites rose from 2013, when there was first a major push by local politicians to have a stronger online presence. It was also different from 2007 when users mostly engaged on SMS, emails, or board sites like Mashada, which folded after the elections. Nendo’s research shows that there are 7 million Facebook users in Kenya, one million on Twitter, and 3.5 million Instagram users, and Kaigwa says politicians are giving a keen interest to these users, given how zealously they unpack government failures and challenge power.

“Social media played an increasing role but so did digital strategy as a whole,” Kaigwa noted, adding that the social media-driven approaches in 2017 have had “wider ramifications” for the internet and politics as we know it in Kenya. “We’ve never seen anything like it before.”

Circumventing traditional media

One thing social networking sites allow candidates is to “bypass mainstream press and spread both information and misinformation,” says Patrick Gathara, a writer and strategic communications consultant. An unsuccessful attempt of this was president Kenyatta’s decision to pull out of the presidential debate co-organized by the Kenyan media, and then turning to Facebook to answer questions—a move for which he was criticized.

Ironically, Mwangi’s social media-fueled campaign ended up receiving wide coverage from international media outlets including Quartz Africa, the New Yorker, BBC, CNN, Reuters, and Associated Press who reported on him more for his high profile as an activist but also for how social media enabled and popularized his candidacy in a country where tribal politics is king.

For young or independent candidates with no political backing or the resources to run a big campaign, social media provides an opportunity to raise small contributions from a large number of people. It was similar to Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign in the United States last year, except mainly with M-Pesa payments rather than credit cards. Mwangi is the exemplar of this trend, after his online appeal for funds raised millions of shillings, drew support from prominent Kenyans, and even garnered a truck donation from a supporter on Twitter.

Mwangi declined to be interviewed for this piece saying he wasn’t doing any interviews on the elections and was taking time off to reflect.

But while social media engagement can be a good way to mobilize resources, it is no substitute for ground campaigns, the prestige of big parties, and the politics of tribe and patronage that define Kenya’s elections. For now, social media doesn’t change the underlying social dynamics in an election, says Nanjala Nyabola, a political analyst based in Nairobi.

“A society that is tribalist offline is going to be tribalist online,” adds Nyabola. And while social networking “may make information travel faster, ultimately, the information is going to reflect more or less the values of the society in question.” Peter Kenneth and Miguna Miguna, who both ran for governor of Nairobi county, are examples of candidates whose social media presence didn’t translate to wins on the ground.

Gathara says that if current social media engagement is maintained, it will become increasingly important, not just in the next election season, but in the years in between. And while we might not know whether social media will still be defined the way it is today, Kaigwa says we will “see a push towards using bots on messaging and chat apps.” The 2017 election, he says, showed the importance of sharing content through private channels and instant messaging apps like WhatsApp and Telegram.

Nanjala says that no matter what, candidates will still have to do a lot of groundwork to deliver their messages effectively. “Social media is a tool and not a movement,” she said. “People should be able to foment political change with pen and paper as well as they do it with Twitter or Facebook. A tool can help move a political conversation but it does not define it.”