Kenya thinks it has a fake news epidemic and these startups are taking on the fight

In its 2017 annual sustainability report, Kenya’s largest company Safaricom said the biggest challenge it confronted during the year was tackling “fake news.”

In its 2017 annual sustainability report, Kenya’s largest company Safaricom said the biggest challenge it confronted during the year was tackling “fake news.”

Blaming the “immediacy and popularity of social media,” the telecom giant said it faced numerous challenges countering fake promotional offers and fraudsters hoping to scam customers. Another widely-circulated allegation claimed its chief executive officer Bob Collymore had been fired. In fact, Collymore has been on medical leave since mid-October.

Through it all, Safaricom’s said its communications department spent 50% of its time monitoring and addressing these issues—an increase from around 10% during the 2016 financial year.

As the country’s leading mobile operator, Safaricom has enabled internet connectivity across Kenya, which in turn has fueled social media use to become a key outlet through where many important conversations take place in Kenya. Yet platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp have also become a conduit for propaganda, particularly during the 2017 general elections.

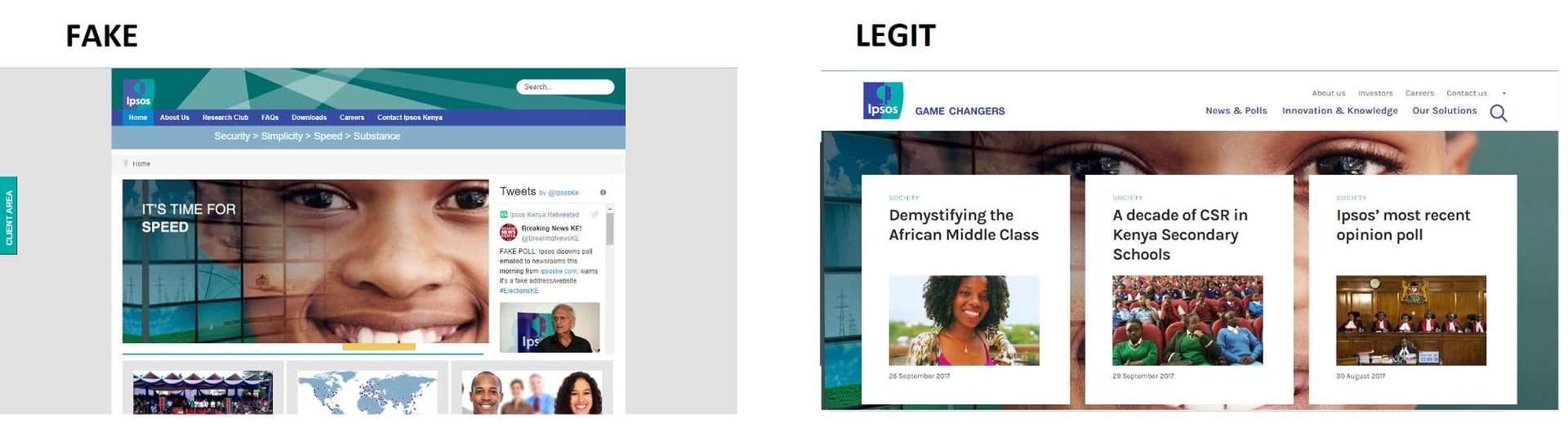

Beyond the political landscape, these deliberate attempts to disseminate false or misleading stories have seeped through to the corporate world, small businesses, and media houses. And while there’s no easy answer in sight, local digital strategists are trying to figure out how to help clients deal with fake news.

“Fake news still has an audience in Kenya,” says Mark Kaigwa, founder of tech research company Nendo. “I don’t see it going away. It’s still useful to many people.”

Samer Ahmed, co-founder of Nairobi start-up Odipo Dev, says there’s been growing concern from their clients on how to respond to fake news. Before last August’s elections, the company tracked false news consumption and employed a robot to analyze the presidential debate.

Ahmed said that interested parties usually wanted them to find fake domains or social media handles, censor out fake items from feeds through browser extensions, or warn followers from certain pages with false content by using targeted ads or bots.

Setting the agenda

Given the fast-paced and sophisticated nature of misinformation online in Kenya, some companies are offering targeted interventions aimed at setting both the record straight and giving citizens the best possible information for decision-making.

One of these enterprises is PesaCheck, considered East Africa’s first public finance fact-checking initiative (“pesa” is Swahili for money). Besides testing the accuracy of media reporting, PesaCheck investigates statistical numbers quoted by public figures with regards to government service delivery similar to BudgIT in Nigeria. As such, PesaCheck has written stories about Kenya’s soaring debts, the actual costs to run the two houses of parliament, and tracked down the roots of a fake story about president Trump signing an executive order that allowed Kenyans only 100 visas a year.

Managing editor Eric Mugendi says their main consideration behind scrutinizing claims is “public interest, and then how potentially damaging such a claim would be.”

Yet, in a personality-driven political realm, audiences on social media can sometimes be duped by propaganda or partisan reporting. That’s why the Nation Newsplex, the data team behind the country’s highest circulating Daily Nation newspaper, decided to go an extra mile. After investigating key electoral issues like economic growth, corruption, education, and health, the platform ensured the material was published online, in print, and was widely discussed in news bulletins on Nation Television.

Nation Media Group’s data editor Dorothy Otieno said sharing the Newsplex findings on all platforms helped reach a socio-economic and politically diverse audience. “We were able to go deeper in our stories and close an important gap,” Otieno said.

Language matters

In a country with more than 40 ethnic groups and almost 70 languages, much of the dissemination of fake stories isn’t only happening in officials languages like English and Swahili. Before Kenya’s repeat elections in October, the non-profit Internews started working with vernacular radio stations in towns across Kenya.

Shitemi Khamadi, a trainer with Internews, says low media literacy and scarcity of resources contribute to spreading misinformation. To counter this, he’s been instructing local broadcasters on how to question their sources vigorously, and to verify photos and videos shared online. And whenever Internews flagged a made-up story, they distributed that content to all the stations in their network “whether we have worked with them or not.”

Yet dealing with fake news and cracking down on those turning social media shares into page views and ad dollars has proved difficult. Even large companies like Facebook, who are testing several ways to make it easier to report a hoax and are working with third-party fact-checking organizations like the Poynter Institute, admit to struggling in solving this. “We’re excited about this progress, but we know there’s more to be done,” says a Facebook spokesperson.