China is getting more aggressive in dismissing US comments about its influence in Africa

The United States is worried about China’s engagement in Africa, and how it is jockeying to spread its diplomatic, military and trade influence across the continent. That much is evident from comments of top US officials, who have recently stated that China’s financing of roads and bridges “comes at a price,” and that it’s new base in Djibouti on the strategic Gulf of Aden corridor is aimed at asserting “power over world trade.”

The United States is worried about China’s engagement in Africa, and how it is jockeying to spread its diplomatic, military and trade influence across the continent. That much is evident from comments of top US officials, who have recently stated that China’s financing of roads and bridges “comes at a price,” and that it’s new base in Djibouti on the strategic Gulf of Aden corridor is aimed at asserting “power over world trade.”

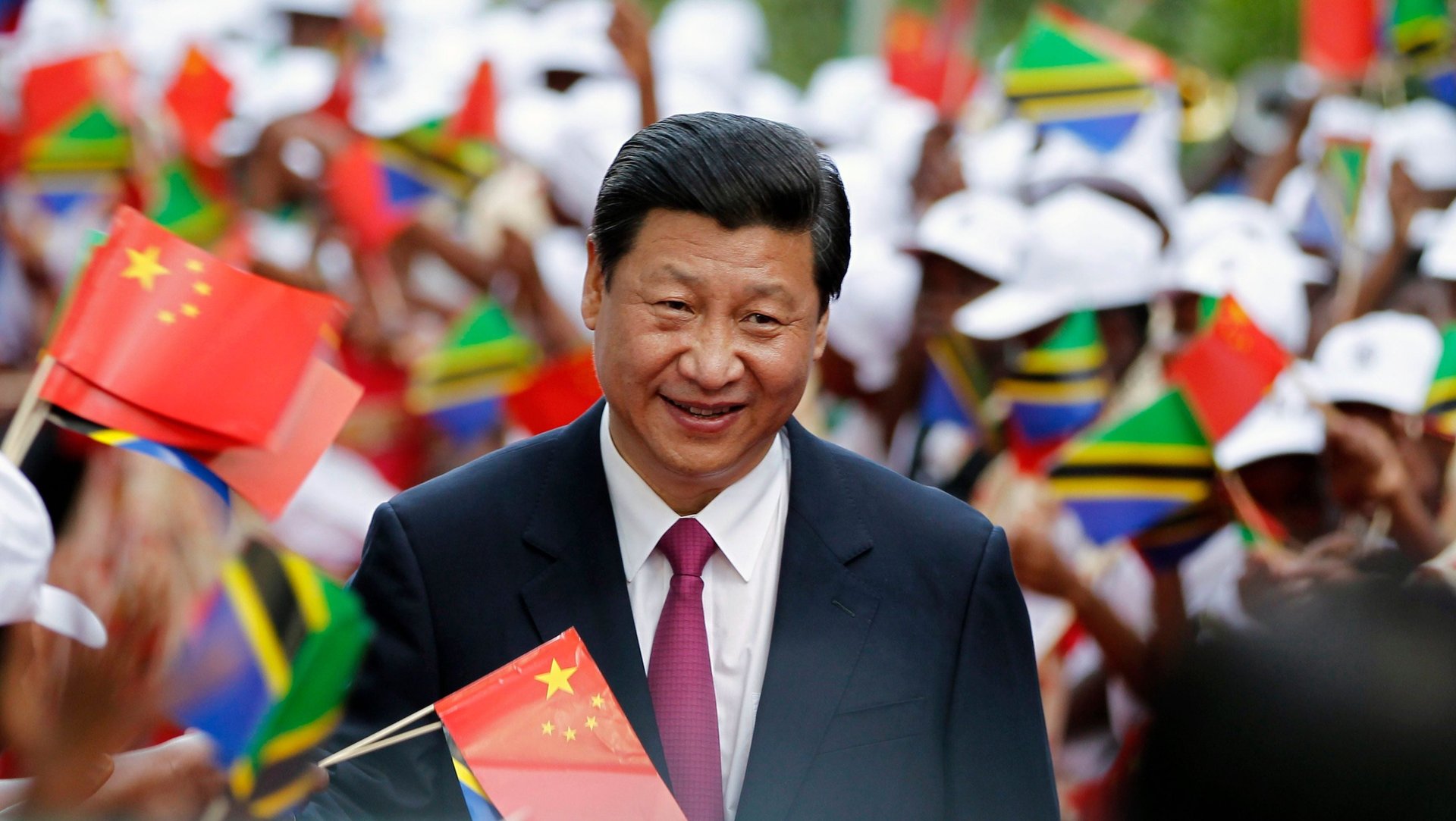

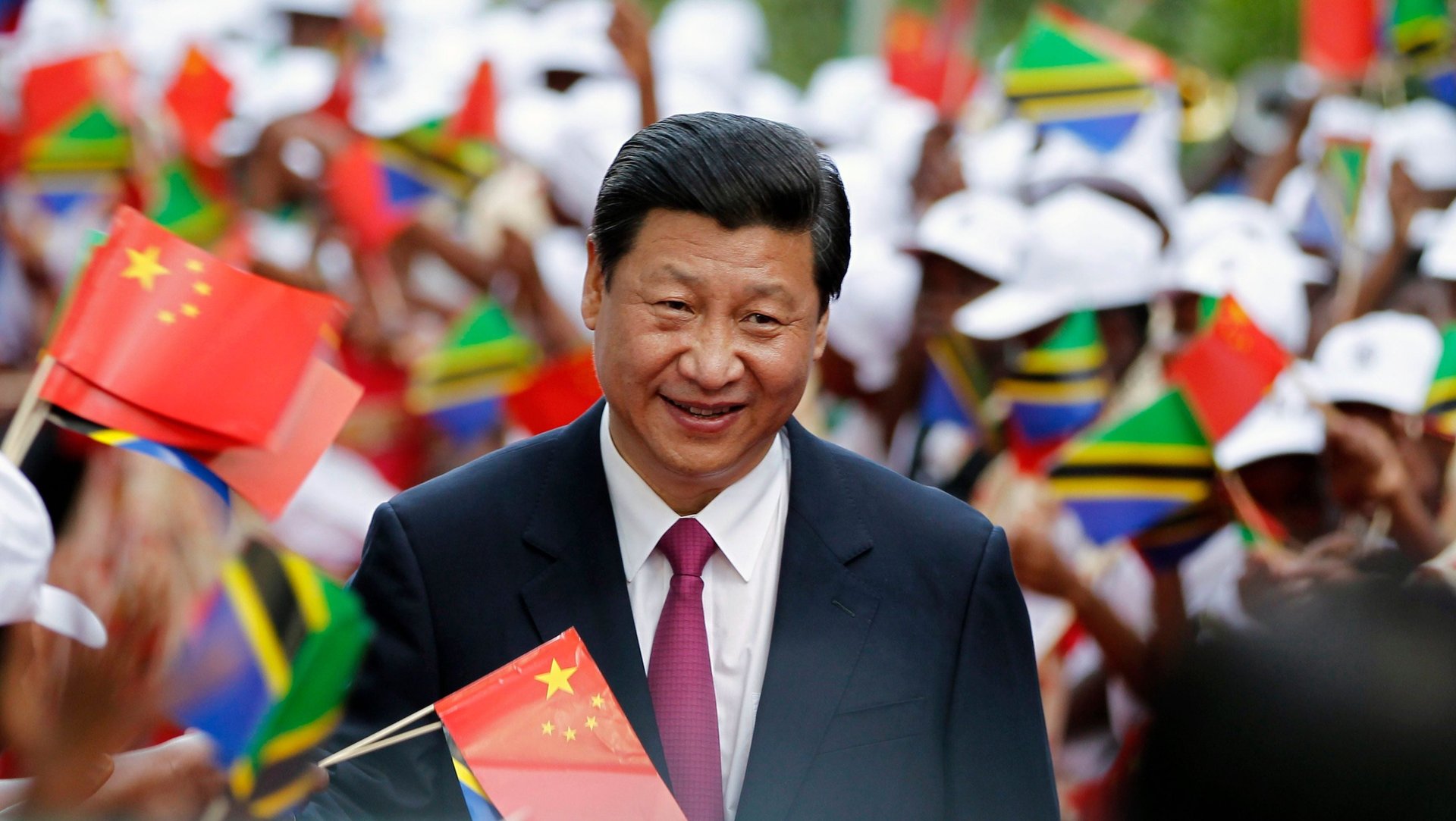

Yet instead of remaining quiet or furtive as has been tradition in the decades past, Chinese officials are increasingly responding to official American remarks, clarifying positions, defending their investments, and countering the narrative that its approach to Africa is purely based on “chopsticks mercantilism.” Through its diplomats and spokespeople, the Chinese say they are pursuing “shared interests” in Africa, arguing that Sino-Africa relations are based on “the vision of sincerity, real results, affinity, and good faith.” The propensity to comment on record also comes as China boosts efforts to improve its image globally besides sending senior officials to visit the continent regularly.

The latest comment from Beijing came after US House Intelligence Committee chairman Devin Nunes said this week his committee will investigate China’s spreading influence in Africa. China’s foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying responded: “There is a Chinese saying which goes “one’s mentality will determine how he perceives the world.” There is also another proverb that “if one suspects his neighbor of stealing his ax, all the behaviors of that innocent neighbor appear suspicious to him,” it refers to someone that harbors groundless suspicions in disregard of facts. We hope that relevant people in the United States can be more open-minded, and aboveboard and refrain from viewing normal cooperation with tinted glasses or interpreting other countries’ goodwill to pursue win-win outcomes with a hegemonic mindset.”

Similarly, in early March, Chinese officials pushed back on former US secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s assertion that China was miring Africa in debt. Lin Songtian, China’s ambassador in South Africa, said Tillerson “regrettably” came to “teach African countries and people to be alert” of China, even though they were “mature enough to engage in partnerships” on their own.

After allegations surfaced in late January that China bugged the African Union headquarters which it helped build, foreign minister Wang Yi described the claims as the works of people having “a feeling of sour grapes” about the achievements of China in Africa.

The official response has also increased as China is blamed for propping up authoritarian regimes, encouraging dependency, underwriting vessels depleting African fish stocks, overseeing shoddy infrastructural projects, and focusing mainly on countries home to natural resources it needs. But Beijing, increasingly aware of this, is pushing back on this narrative, highlighting the deployment of peacekeepers in Mali and South Sudan, providing scholarships, besides its educational and technological transfer initiatives.

As Zhou Yuxiao, China’s ambassador to the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, recently said: “I have met the African leaders. They are all optimistic about our cooperation. … I have not found anyone distancing themselves from this partnership.”

“Now there seems to be a different media strategy,” said Cobus Van Staden, a South African academic, speaking on the China in Africa podcast recently. For years, he argued, it was standard procedure for Chinese officials “to essentially go into a defensive crouch” whenever criticism was leveled in the Western or African press. But now, “they are a lot more aggressive and they are a lot more combative in kind of taking on and fighting or refuting points of criticism in the media.”