Juba, South Sudan

Anthony Kpandu took a delegation from his party, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), to China last year to train with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Kpandu is in charge of special working groups at the general secretariat for the SPLM, the liberation movement turned government party that helped South Sudan gain independence from Sudan in 2011. Wearing a button that says, “I love SPLM,” a paisley tie, and a loose tan jacket, he reminisces about his trip to China in detail, down to every day’s itinerary.

They visited the Central Party school in Beijing, toured industrial zones, drank various types of green tea, and walked part of the Great Wall. Kpandu’s favorite part was Shanghai, with its glittery commercial district, Pudong, high-speed Maglev train, and sprawling airport. “It was magnificent. You can’t believe it, but it’s there. I’ve never seen anything like it,” he says from his office in Juba.

In the 1970s, China actively tried to export its communist revolution to Africa, one of Beijing’s few diplomatic engagements at the time. Now, Beijing is promoting a more subtle movement: support for China and and its model of development. Instead of relying on Chinese emissaries in African countries, Beijing is bringing thousands of African leaders, bureaucrats, students, and business people to China.

It’s a campaign that achieves several goals at once. The trips help solidify political and business ties between China and its partners on the continent. Like other development partners, China gets to help build capacity in African countries. Most importantly these exchanges cultivate partners on the continent who are more likely to be sympathetic to China and its way of doing things.

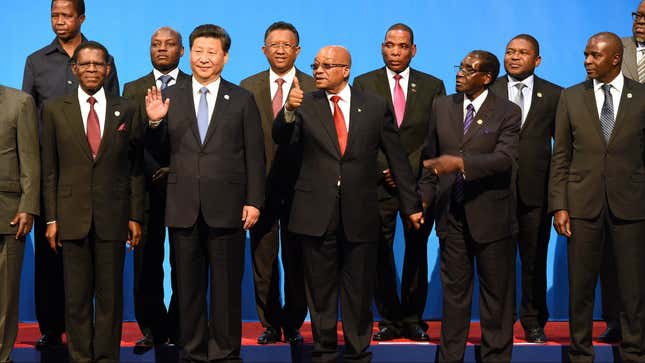

China has been hosting these trainings and exchanges in Africa since as far back as the 1950s when it first established diplomatic ties with Egypt. Over the past decade, the trainings have grown in both volume and profile. Kenya’s Jubilee party, created before the country’s contentious election this year, received trainings from the Chinese Communist Party in China. The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front also takes inspiration from the the CCP while South Africa’s African National Congress regularly attends workshops in China and has modeled some of its party trainings on the CCP.

China is particularly interested in the next generation of African elites. Last year, Beijing announced it would invite 1,000 young African politicians for trainings in China, after hosting more than 200 between 2011 and 2015. Thousands of African students are pursuing undergraduate and graduate degrees in China on scholarship programs funded by Beijing. As of this year, more Anglophone African students study in China than the United States or the United Kingdom, their traditional destinations of choice.

Chinese officials are quick to say these scholarships and trainings are not an attempt to remake Africa in its own image. In theme with China’s self-avowed policy of noninterference, Beijing likes to stress that it does not tell its partners what to do.

“We’re not saying the Chinese model should be copied but to share lessons. It’s to give them the concepts so that they can adapt and find their own solutions,” says Zhang Yi, China’s economic attache in Juba.

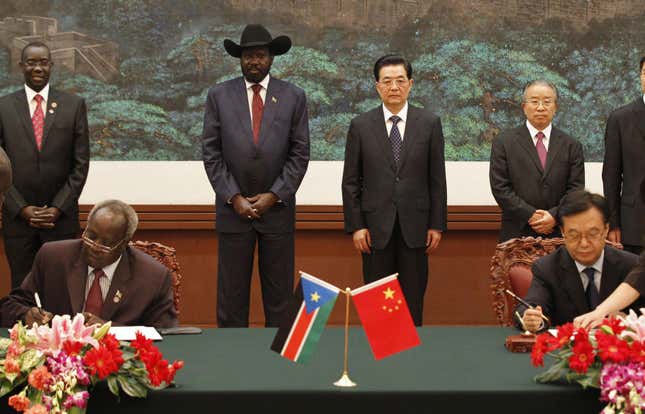

But South Sudan, the world’s youngest country, may be particularly impressionable. It is still developing its government institutions and political system, amid a four-year civil war that has split the former liberation party into several factions. China, which has major oil interests in the country, was one of the first countries to recognize South Sudan and remains engaged with the country, with 2,600 peacekeepers and more than 100 Chinese businesses and investors.

“The SPLM seems to believe that given shared experience in historical struggle against imperialism and colonialism, there are much similarity and common ground between SPLM and the [Chinese Communist Party’s] origins,” says Yun Sun, a fellow at Brookings Institution who has written about party to party exchanges between China and African countries.

“It does raise the question what kind of political future South Sudan faces as a result. If we do believe in the universality and desirability of the democratic system, the model represented by the Chinese experience and its popularity may not be the most encouraging,” she says.

Hundreds of South Sudanese government officials, business people, and students, attend training or schooling in China, every year. Delegations from the SPLM in Juba travel to China several times a year to study with the communist party. Bureaucrats from the government’s ministries of culture, transport, health and more go every month for trainings. Even before South Sudan became an official state, officials were hosted in China to attend workshops on poverty alleviation, managing public opinion, and building a party.

China has given at least 4,100 scholarships and training programs to South Sudanese students and officials since 2011, when the young country was established. In August, China pledged to offer at least 240 more scholarships. The China-South Sudan Friendship Association, headed by a former foreign minister and partly sponsored by the Chinese embassy, embeds South Sudanese business people with Chinese companies.

South Sudanese and Chinese officials like to say they are learning from each other, sharing experiences from one former liberation movement to another. Both the Chinese Communist Party and the SPLA grew out of armed guerrilla movements. The SPLM fought for decades for independence from the north. The party also has its roots in socialism, identifying first with the Soviet Union during the Cold War. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the SPLM turned to the United States as an ally but even today, SPLM officials still use the title “comrade.”

But that’s where the similarities end. The Chinese communist party transformed itself into a government that maintains one-party rule over a country that is mostly one ethnicity, Han Chinese. In contrast, the SPLM in Juba is locked in a civil war with splinter parties, divided by region and ethnicity in a country home to more than 60 ethnic groups.

Zhang, China’s economic attaché to Juba, believes some aspects of China’s model of government could help South Sudan, for instance, a stronger central government. “There’s no history of a centralized government in the past, which means there’s no process of nationalism. So the people, they still stay grouped by tribe.”

But not all lessons from China should be learned. Under Xi Jinping, China has tightened its stranglehold over civil society. South Sudan is already familiar with some of these tactics. Local journalists are intimidated into silence or killed.

“When you go to China they will not be talking about democracy,” says Samson Wasara, vice chancellor at the University of Bahr el Ghazel in Wau state, where he says as many as 300 graduate students are pursuing degrees in China. “In 10 years time, one of [these students] will be the leader of South Sudan.”

Wasara fears the SPLM already sees the Chinese communist party as its role model, a trend that he sees replicated across the continent. ”Most Africans are switching from the West to China,” he says. He worries that China will become South Sudan’s main role model. The United States and other Western powers supported South Sudan’s bid for independence and are still involved in aid and mediation efforts in the country today. “It will be a disaster for us, especially for those who know the value of human rights, democracy, free speech,” Wasara says.

That may already be happening. The SPLM is at least taking inspiration from the CCP. Kpandu says he reads from his copy of Concise History of the Chinese Communist Party every day. He wants to establish a youth arm of the SPLM, modeled after the Communist Youth League of China. After reading about Mao Zedong’s famous declaration that women “hold up half the sky,” he has pledged to recruit more women into the party.

“China has been an example to us. We will always look up to them,” he says from his office at the General Secretariat for the SPLM. The secretariat manages the day to day operations of the party, and he is preparing an SPLM training on code of conduct and party structure.

Kpandu says South Sudan won’t copy everything from China, claiming that South Sudan won’t be a one-party state. President Silva Kir, head of the SPLM in Juba, is pushing for an election in 2018 despite warnings from the United Nations that a legitimate election is near impossible and risks causing more violence. Others say that African elites and students select what lessons they choose to take from China’s example.

“The young Africans are not robots and tabula rasa such that the Chinese will just stuff them with whatever they want. The students will take the best of China and leave the bad there in China and go back to Africa,” says Adams Bodomo, director of the Global African Diaspora Studies Research Platform and professor of African studies at the University of Vienna.

The exchanges and scholarships may be more about inspiring admiration and sympathy than emulation. Others who have attended diplomatic trainings say the teaching is basic — how to shake hands or how to sit with a senior dignitary. (If you’re the host, the dignitary should be to your right.)

A South Sudanese diplomat who spent a month in China for a training of diplomats said his trip was mostly focused on showing off China’s achievements. He was taken to visit villages built from scratch, well-run rural hospitals.

“When we went they told us a lot of stuff about China itself and China’s industrialization. It’s more about public relations,” he says, asking not to be named because he was not authorized to speak to media.

This public relations campaign is at least partly working. The so-called China model is gaining traction across the African continent. According to an Afrobarometer survey last year of 56,000 people in 36 African countries, 30% of respondents said the United States was a better model for development, compared 24% who ranked China first. In Southern Africa, North Africa, and Central Africa, China was on par or ahead of the US.

On his trip to China, Kpandu was also impressed with the surveillance. He visited a police control room in Nanjing and when his group was taken to a special economic zone outside the southern Chinese city, a drone filmed them the entire 72 mile journey.

Back in Juba, he wrote a report recommending his government buy some of these drones to deal with “unknown gunmen,” a moniker that often includes government soldiers themselves known for robbing and attacking civilians in the capital. “We have learned quite a lot from the CCP,” he says.