This album documents the lasting impact of Sudan on African music

Sudan was once Africa’s largest country: its vast region extending from the edge of the Sahara in the south, embracing the confluence of the Blue and White Nile at its capital, and straddling the Red Sea along its northeastern border. And much like its expansive geographic contours (somewhat curtailed since South Sudan’s 2011 independence), the Sudan’s artistic and musical influence held a central position in Africa, and especially along the “Sudanic Belt,” which stretched from Djibouti and Somalia in the east through to Mauritania in the west.

Sudan was once Africa’s largest country: its vast region extending from the edge of the Sahara in the south, embracing the confluence of the Blue and White Nile at its capital, and straddling the Red Sea along its northeastern border. And much like its expansive geographic contours (somewhat curtailed since South Sudan’s 2011 independence), the Sudan’s artistic and musical influence held a central position in Africa, and especially along the “Sudanic Belt,” which stretched from Djibouti and Somalia in the east through to Mauritania in the west.

Yet a tapestry of sociopolitical misfortunes, economic embargoes, coups, censorship, religious edicts, and inimical policies changed all that, relegating its prolific music industry into the backwater, and leaving artists jailed, dead, and exiled.

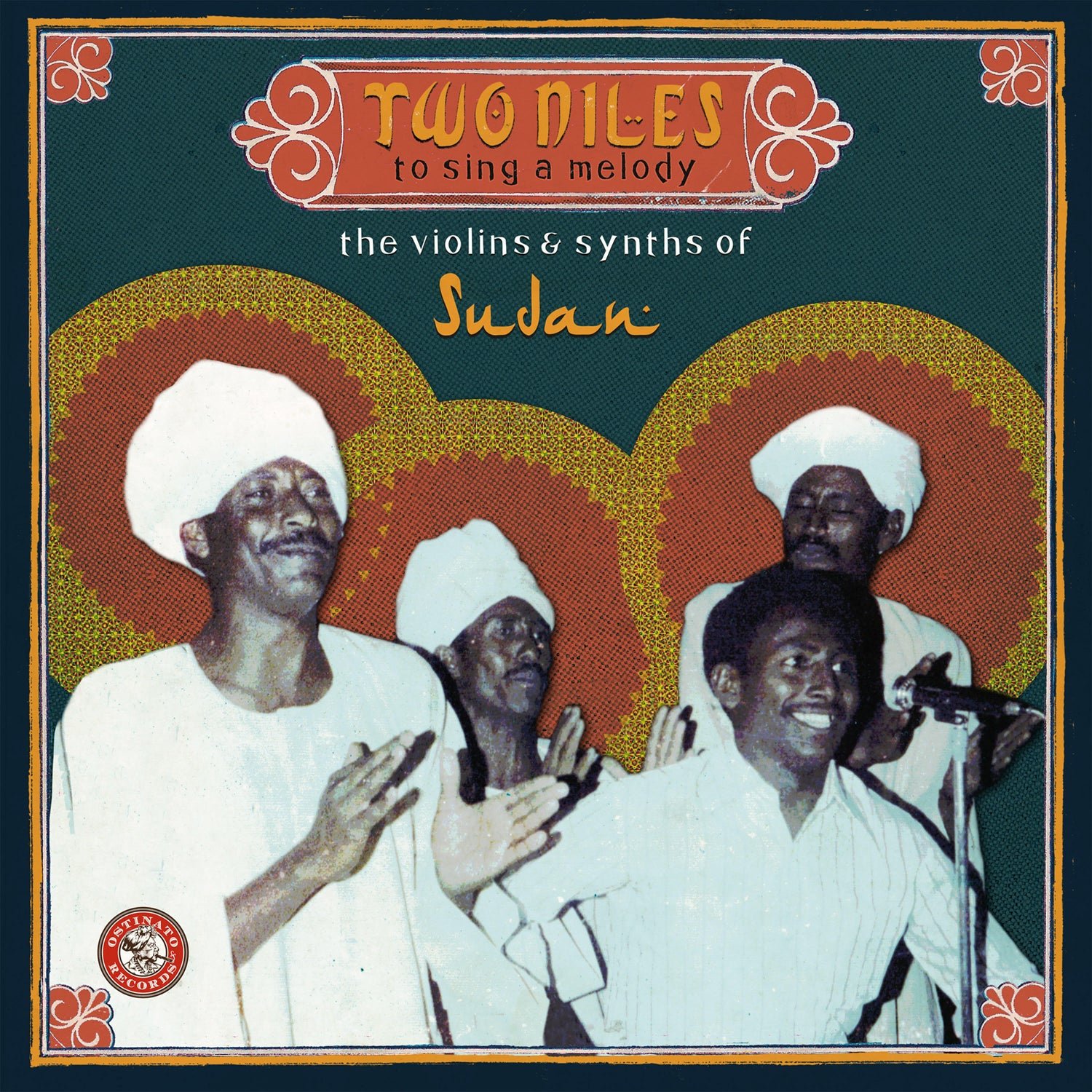

Two Niles to sing a melody, the fifth album from the New York-based collective Ostinato Records, deals with this rich history from Sudan. Through 16 tracks, the collection traces the golden era of Sudanese melodies, starting from the 1970s through to the tunes composed in exile in the 1990s. The songs, employing the violin, guitar, drum, and the oud, signify the wide berth and infectious nature of Sudan’s musicians including Emad Youssef, Hanan Bulu Bulu, Abdelmoniem Ekhaldi, and global superstar Mohammed Wardi.

The compilation particularly highlights the smash hits that came out of the capital Khartoum—hence the title—not as a way to diminish the rest of the nation’s soundscape contributions but to underscore how political oscillation at the center “nurtured and killed one of the most beloved music eras in Africa.”

Finding and curating this collection, however, was easier said than done. From the onset, Ostinato was faced with the challenge of accessing the archives at Sudan’s national radio, whose master reels, they found, is today “outsourced to national security services—the equivalent of having the CIA guard the doors of the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C. It is entirely off limits.” To find these songs, the company’s team traveled to neighboring countries like Ethiopia, Djibouti, and Egypt where collections of cassette tapes were more readily available.

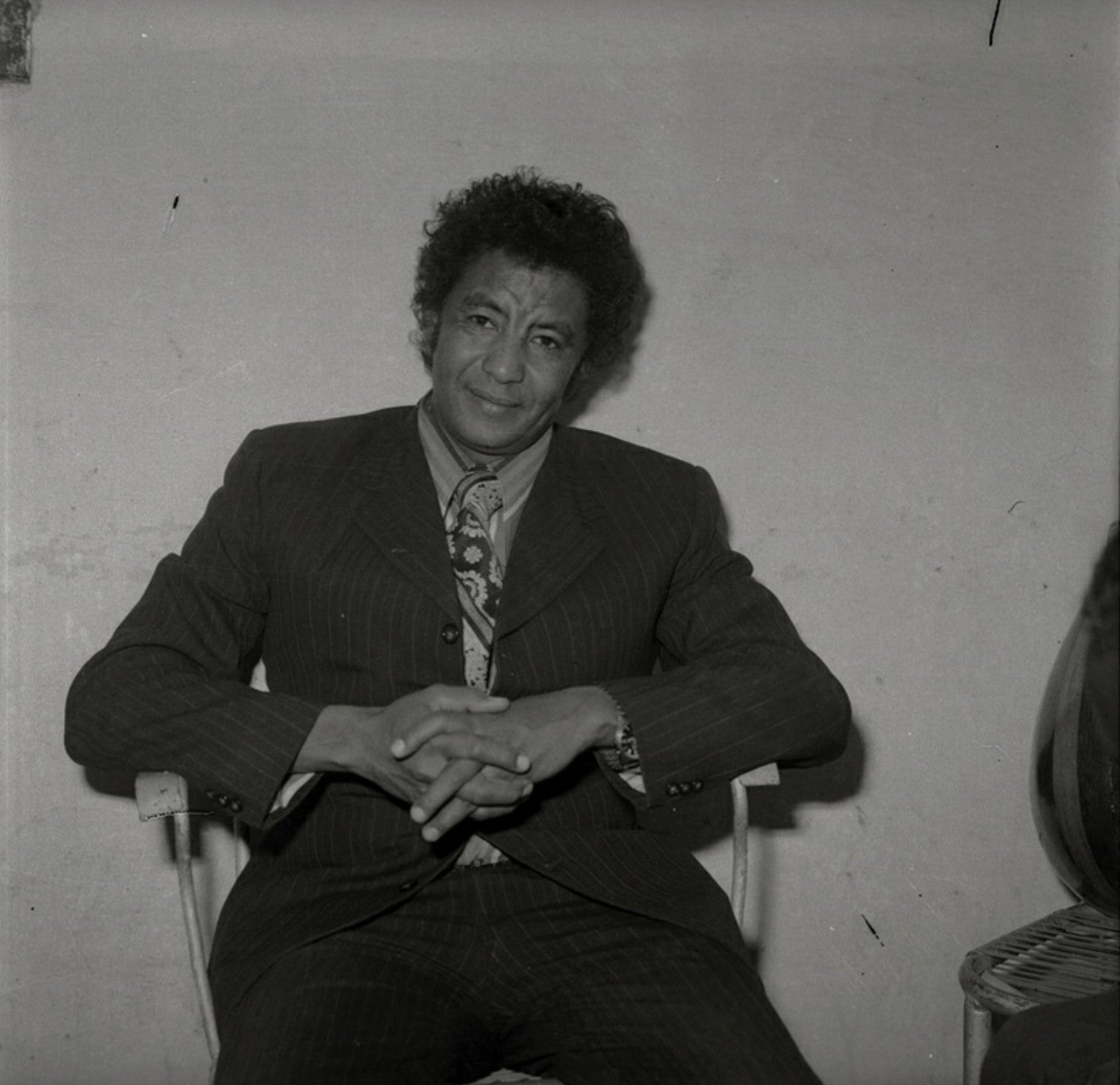

This scheme of tapping an expansive network to dig out treasure troves is something that has worked for Ostinato before: its founder Vik Sohonie has traveled from Haiti to Cape Verde and Somalia to find, sift, compile, and digitize rare gems that often sit untouched or inaccessible in archives or people’s homes. One of those albums Sweet as broken dates about Somali music was nominated for a Grammy last year.

Through the Sudan collection, Sohonie and his co-compiler, the 1970s actress and poet Tamador Sheikh Eldin Gibreel, hope to not only showcase the importance of music to Sudanese life but also its lasting and widespread impact across the continent. “Brand Sudan was built by music, its greatest ever export,” says Sohonie. The album is also accompanied by a booklet with interesting interviews including with the sons of Wardi and Khojali Osman, the latter of whom was killed in 1994.

And while Sudan’s musical heritage might have slipped from the global stage in recent years, Sohonie says that doesn’t diminish its power. “It remains wounded but unbowed.”