Uber’s innovations in Africa have helped shape its global operations

It’s been exactly five years this month since Uber launched in Johannesburg, South Africa, marking its first entry into the African continent.

It’s been exactly five years this month since Uber launched in Johannesburg, South Africa, marking its first entry into the African continent.

Since then, the ride-hailing service has disrupted Africa’s fragmented transport market, garnered 1.3 million riders in sub-Saharan Africa alone, and grown its footprint to 15 cities in 8 countries including North Africa. But the journey has also been a bumpy one, marked by violent protests, price wars, regulatory challenges, and accusations of growing into a monopoly.

Quartz spoke to Alon Lits, Uber’s general manager for sub-Saharan Africa, to discuss the company’s tussle with drivers and regulators, its support for African innovation, and its determination to expand to more countries including Rwanda and Côte d’Ivoire.

Quartz: How impactful has Uber been in its five-year operation in Africa?

Alon Lits: South Africa was the first country for Uber outside of the US where we had three cities operational at the same time. Part of the reason why that happened, and why the business has been impactful across the continent is the value we bring. If you look at the segments of the market that we currently cater for, [they are] individuals who would ordinarily rely on their own private vehicle. Given our launch, all of a sudden, for that segment market, there was now an affordable and reliable public transportation option.

The next piece is on the driver’s side, and unfortunately, we know that unemployment is a reality in South Africa, Kenya, and a lot of the cities and countries where we operate. I strongly believe that Uber creates stronger and meaningful economic opportunities for our driver partners.

It’s really been about looking at how are people are moving around our cities. Is there something which we are currently not catering to and how can we localize our product offerings to ensure that we can really form part of that mobility framework in our cities? 2017 was really about focusing on getting those products right and getting those cities scaling and growing. In 2018, what you would have seen is introducing lower-cost options across our cities, the first being the CHAPCHAP product in Nairobi, where we wanted to ensure we could offer a lower cost product to riders but at the same time ensure that the economics made sense for drivers. Also launching the POA [rickshaw] product in Dar, and the BODA [motorcycle] product in Kampala.

QZ: What does your expansion strategy in Africa involve? And what other locally-popular forms of motorized transport are you considering?

AL: For the cities where we currently operate, we are always looking at whether there are products which meet the need in the way people in the city are moving around. For example, Kekes [tricycles] in Nigeria. Is there a CHAPCHAP equivalent that we can look to introduce in Ghana? The next issue from an expansion perspective is obviously for the existing countries where we operate: are there opportunities for us to launch in new cities? Maybe that would be a launch with just a BODA product or just a tuk-tuk product.

And the final bucket would be expansion into new countries, we are always looking at opportunities. We don’t have any firm timelines in place but I can tell you we are looking at the likes of Rwanda, Ivory Coast, Senegal and, potentially, Mauritius. We are really encouraged by the regulatory changes that we are seeing in Ethiopia. If I think of the first kind of geo-expansion, I don’t think Ethiopia would form part of it, but when we are thinking a little bit further into the future, it’s definitely top of mind and something that we are going to be looking at more seriously going into 2019.

What are some of the lessons learned from Uber in Africa that have been applied to its global operations?

Cash is probably the best example of that. Nairobi was the second city for Uber globally to test cash as a payment method. We got consistent feedback from both riders and drivers that we needed to launch a cash option. So we launched a pilot in Nairobi where we tested cash as an option over a two-month period, and it was incredibly successful. Over that two-month period, the business grew over three times. Cash is now available in cities around the world and I think that was the most pivotal or the most impactful innovation, and I do believe Africa played a large part in driving the global strategy around cash.

In a lot of cases, what we’ve seen in the cities where we operate is drivers who are operating vehicles don’t have access to capital and then have to work for someone else. This means they are sharing the revenue that they generate with the vehicle owner, and they are only getting paid a portion of that revenue. We hired a South African in 2015 to help us build a vehicle solutions program for Uber in South Africa. What this person did was to work with financial services companies to say to them, “If you look at this individual’s bank statements, because they are only getting paid a portion of the fares that they generate, they may not be able to qualify for a loan. But if you look at their track record using the Uber app and you look at what their historical earnings have been, what their rating has been, how many trips he or she has completed, that almost becomes a proxy for a credit score.” They took that approach and we did the first deal with WesBank in South Africa. We’ve expanded that to Barclays and Stanbic Bank in Nairobi.

Could you tell us about the lessons learned from dealing with African regulators?

I would say that overall the reception we’ve received from regulators is a positive one. If I could say what we could have done differently, I think when we initially launched we would launch in a city and then engage with regulators down the line. Whereas now we engage with regulators upfront, so the first time that they hear about Uber is not from a newspaper but rather because we’ve had a conversation, we’ve explained the app, and we’ve explored ways that we can both partner.

Another big piece is ensuring that we engage with the existing taxi industry up front before we launch. Because from our perspective, it’s really not about Uber or taxi, it’s about Uber and taxi and how the two can co-exist. Dar es Salaam is a good example of that where a lot of the operators using our technology there are from the taxi industry but use Uber during the downtime to increase their revenue earning opportunities.

QZ: How are you handling drivers’ divergent preference for cash vs. card payments in African cities?

AL: In South Africa, drivers were concerned for their own safety before accepting cash trips. They wanted to have the ability to not accept a cash trip if they weren’t comfortable. And they wanted some form of verification process for riders who were signing up using the cash payment. So what we introduced was for riders in South Africa who signed up with the cash payment option to link their Uber account to their Facebook account. And there are checks and balances that happen in the background to ensure that is a legitimate Facebook account and not an account someone has just created.

The next thing we did in South Africa was introduce the cash indicator. So when the trip comes through, drivers can actually see is that a card or a cash trip. If the driver is uncomfortable with the location the request is coming from or they are not comfortable with doing the cash trip on that point in time, they can not accept that request and they won’t be penalized in any way.

Cash is the majority for trips in both Nairobi and Dar and up until now, we haven’t had a scalable way for drivers to pay their service fee back to Uber. We recently launched a partnership with a company called Direct Pay Online where drivers now have a way to repay the service to us, and they are indifferent to whether that happens in a cash or a card trip.

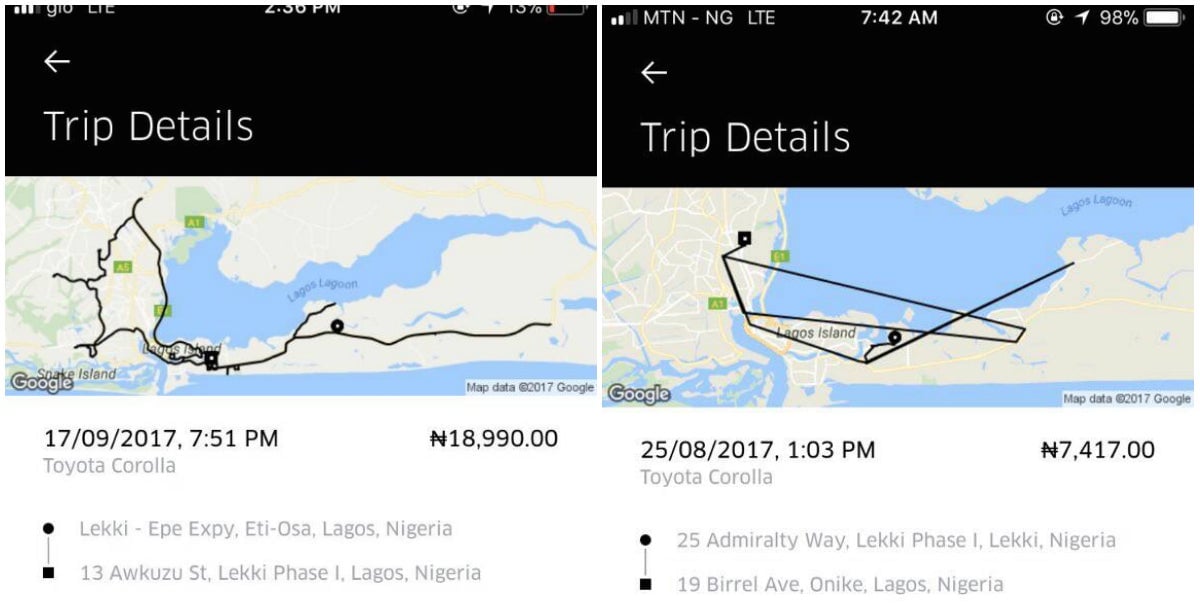

QZ: We ran a story last year of some drivers in Nigeria using fake GPS to inflate prices. How are you tackling that?

AL: It’s clearly a violation of our community guidelines. That type of fraudulent activity completely undermines the trust that Uber was built upon. We’ve got checks and balances in place where our systems are looking at fraud by either riders or driver partners who are trying to game the system. We do have automated rules that are in place which either warns if this is the first breach of the community guidelines or permanently deactivate any accounts associated with that fraudulent activity depending on the severity. And if a rider were to report that to us, and for whatever reason, if our system hadn’t picked that up yet, we would ensure that trip was fully refunded.

QZ: Fluctuating fuel prices have led to drivers’ strikes in South Africa. How are you dealing with these surges?

AL: We offered an incentive to drivers where they complete a certain number of trips each week and we would cover the incremental cost in essence of what it would cost them to fill up the tank. Part of what we want to see happen is where that fuel price is going to go. Is it going to continue to increase and is it close to an all-time high, or is it possibly going to decrease? Until we get a better sense of that, we’d rather not pass on that cost increase to customers but at the same time, we want to ensure that drivers don’t feel the pain.

How are you harnessing local talent in Africa? And what are the ways in which you are supporting local companies?

There are a lot of businesses across the value chain who we try and connect with our driver partners. We’ve got our greenlight hubs, and something we are ensuring is that there can be vendors who are making goods and services available to our driver partners.

On the tech side, Nairobi was the first African city where we did Uber Pitch, which provides entrepreneurs with the opportunity to pitch to investors. Something else that we’ve started in SA is what we call an Innovation Masterclass. This is aimed at students who are still at school where the intention is to expose them to opportunities and provide them with a broader understanding of potential career paths they can follow with a focus around science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

In SA, we’ve got this partnership with Aura, which is a local nationwide response innovation network. In Kenya, we’ve got a similar partnership with a company called Flare, where they dispatch ambulances using an app. So we are always looking at local partners who can provide value to either riders or drivers and looking at ways of integrating with them.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.