Tanzania’s government is casting itself as the nation’s sole custodian of data

Tanzania’s government wants to have exclusive control over who collects and shares data about the country.

Tanzania’s government wants to have exclusive control over who collects and shares data about the country.

In a bill tabled in parliament this week, the government aims to criminalize the collection, analysis, and dissemination of any data without first obtaining authorization from the country’s chief statistician. The key amendments to the Statistics Act also prohibit researchers from publicly releasing any data “which is intended to invalidate, distort, or discredit official statistics.” Any person who does anything to the contrary could merit a fine of not less than 10 million shillings ($4,400), a jail term of three years, or both.

Officials have said the amendments are being passed as a measure to promote peace and security and to stop the publication of fake information. Critics, however, argue the laws will curtail both the collection of crucial data and the ability to fact-check and hold official sources accountable. Opposition members in parliament also said the law could target institutions and scholars releasing data that isn’t in favor of the government.

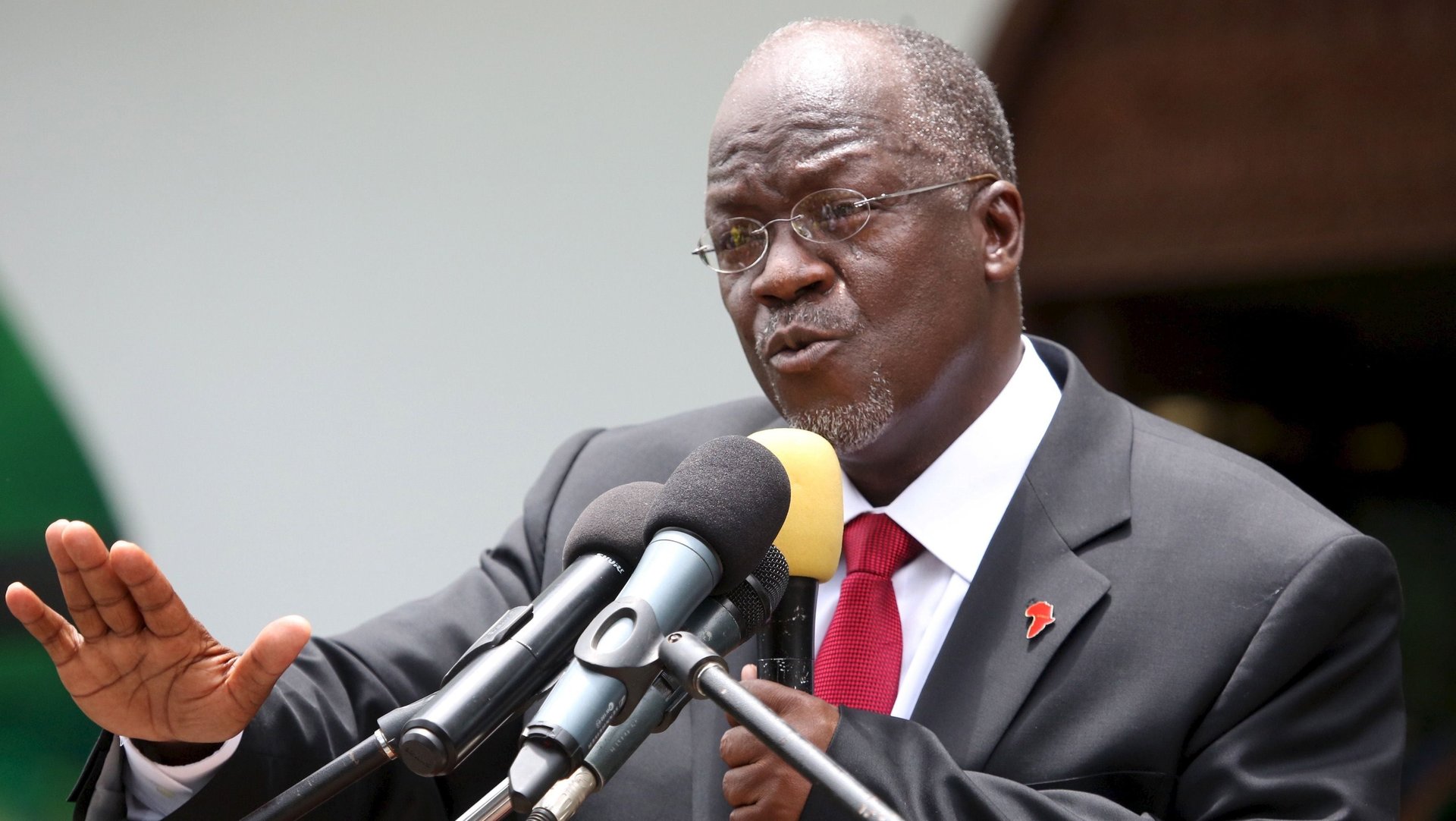

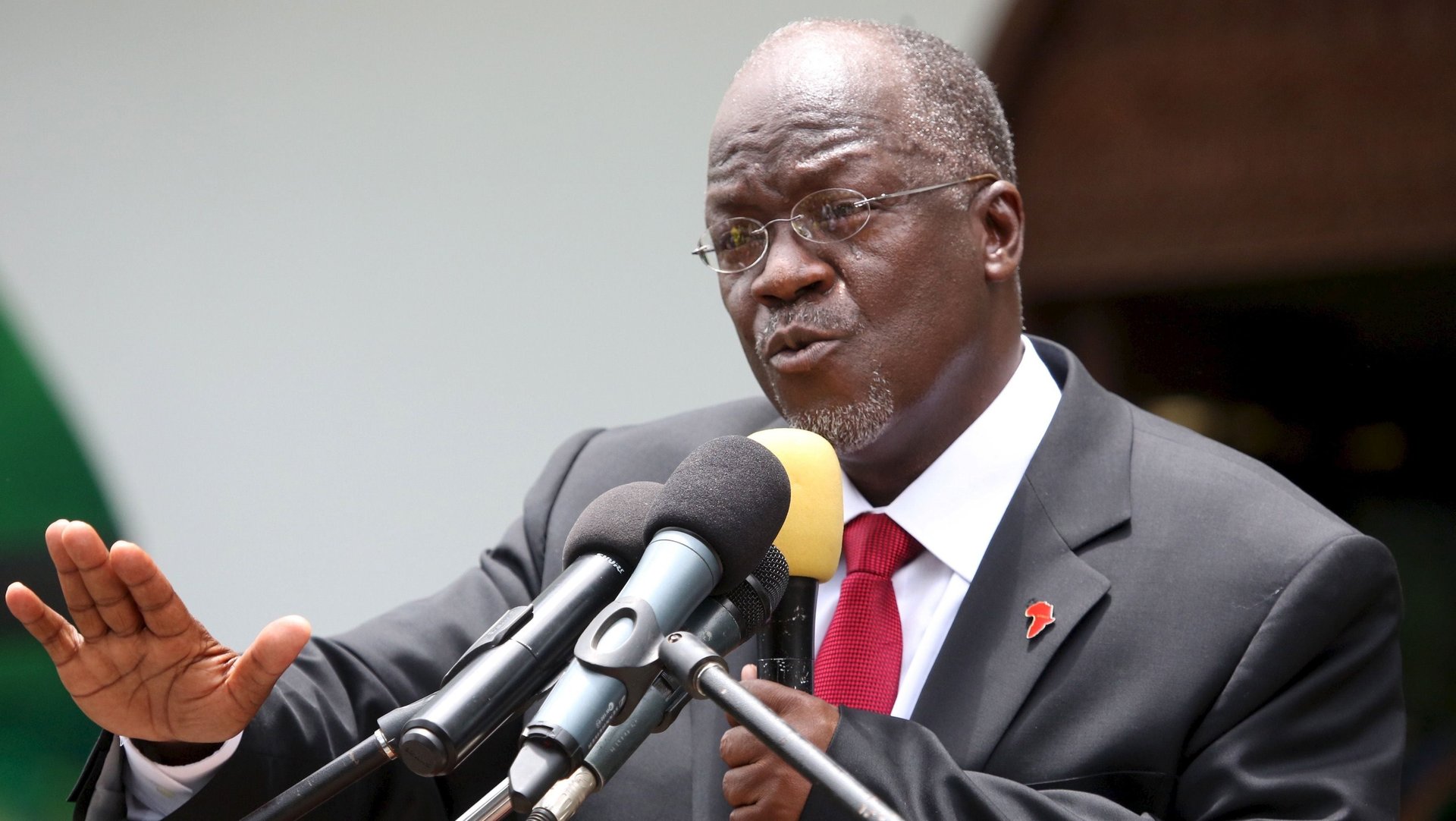

The latest amendments represent a continuation of president John Magufuli’s crackdown on free speech and independent media since coming to power in 2015. Even though he was elected on an anti-corruption platform, his administration has closed newspapers and radio stations and arrested journalists.Magufuli has also banned everything from the export of unprocessed minerals, pregnant girls in schools, and public rallies—earning him the title of “The Bulldozer.”

As part of new online regulations this year, the government said it would charge over $900 to license bloggers. The law was criticized for affecting the nascent tech sector and led to the closure of the East African nation’s top homegrown online platform, Jamii Forums.

Yet the move to ban independent data collection could be damaging given how much quality information could help in national development. African nations increasingly lack evidence-based research that could inform how they formulate national policies. And many times in Tanzania, independent actors fulfill this gap, providing data on flood-prone areas to avoid disasters, or documenting citizens’ needs—something that isn’t captured in official government statistics.