An African American artist’s “remixing” of apartheid-era images is raising questions about appropriation

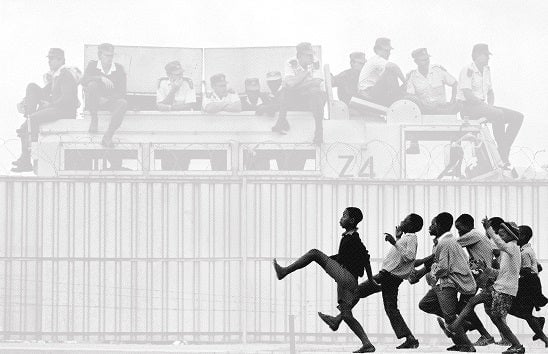

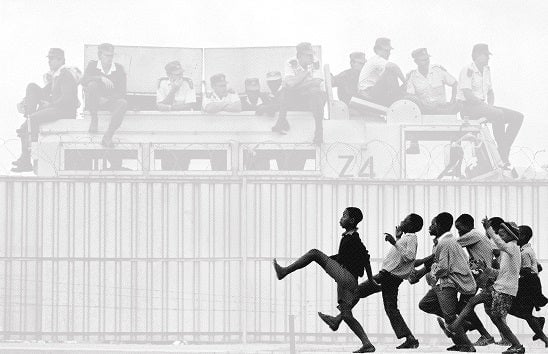

Wandering around this year’s Johannesburg Arts Fair in September, photographer Graeme Williams stopped dead in front of a familiar image. The photograph of black South African children marching past a tank of white police officers was his—except that it wasn’t.

Wandering around this year’s Johannesburg Arts Fair in September, photographer Graeme Williams stopped dead in front of a familiar image. The photograph of black South African children marching past a tank of white police officers was his—except that it wasn’t.

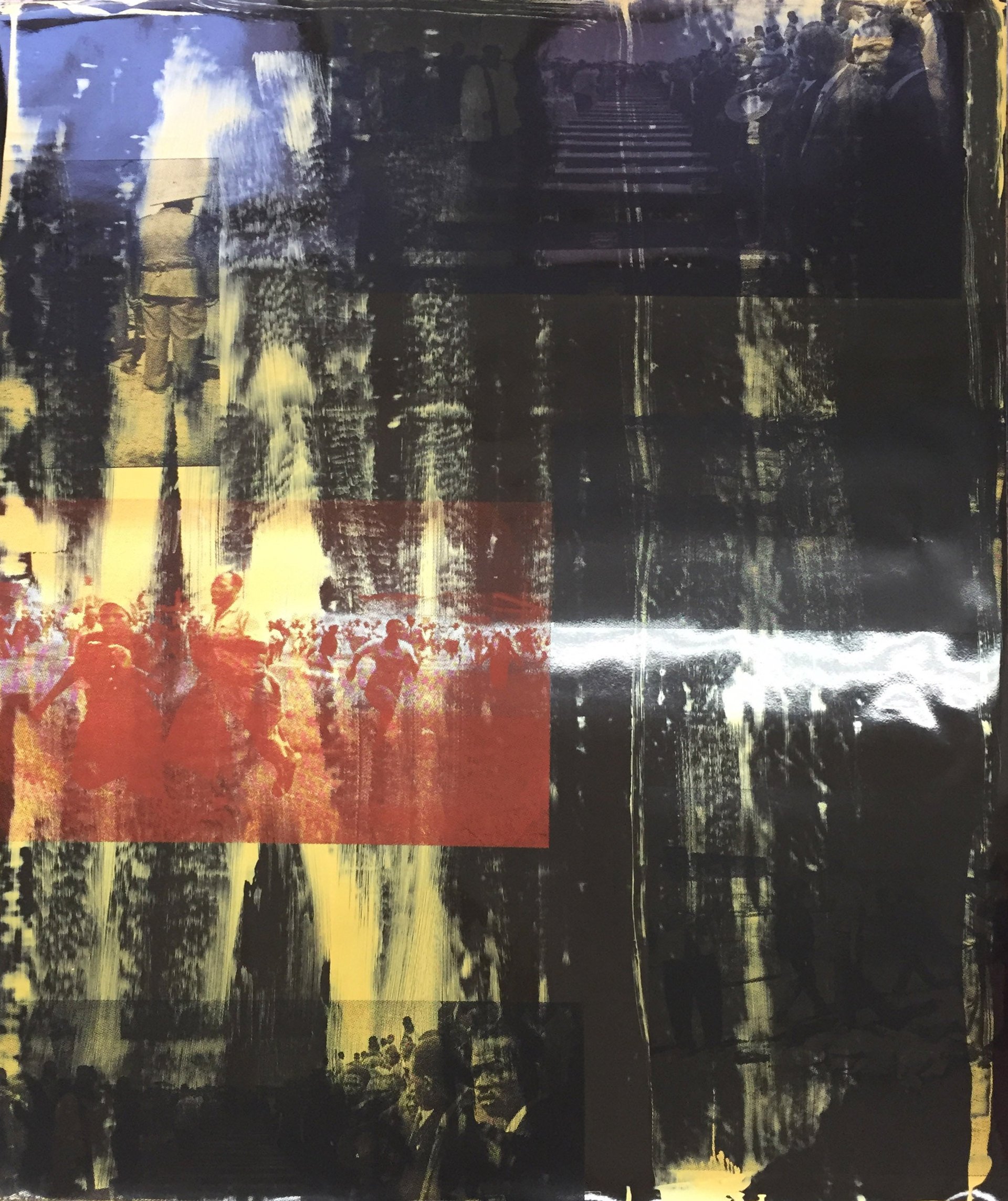

The image had been recreated by African American conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas as part of his series History Doesn’t Laugh. Days later, acclaimed anti-apartheid photographer Peter Magubane learned that his work had also been repurposed by Thomas. The incident threatened to overshadow the three-day art fair and continues to fuel a debate around appropriation, free speech and the power dynamics at play in the creative spaces between South Africa and the United States.

“It’s a dangerous moment when we start we to tell people what they can and can’t talk about, what they can and can’t focus on when they’re making art,” Thomas told CBS News (video) last week. “Censorship was one of the critical tools of the apartheid government and oppressive regime.”

Williams told The Guardian newspaper that Willis’ recreation of his photograph amounted to “theft and appropriation,” because it had barely been changed nor had he been informed of its use. The photographer was further shocked by the $36,000 price tag.

“I think of it as more akin to sampling, remixing, which is also an area that a lot of people said for a long time that rap music wasn’t music because it sampled,” Thomas told the newspaper.

Those “remixed” images, however, depict a particularly painful part of South Africa’s history and their repurposing evokes a public pain for black South Africans, Magubane’s daughter explained to CBS. In South Africa’s post-apartheid constitution, human dignity trumps freedom of speech, a value Americans hold dear.

Thomas says his work examines photography, history and the connectedness of political movements. Whether he is in fact guilty of copyright infringement is a legal issue, he told CBS. The photographers on the other hand are reportedly pursuing a possible lawsuit, even after Willis reached out to them.

The Goodman Gallery, which represents Thomas in South Africa and exhibited his work at the art fair, said they removed the works after Williams’ complaint of unauthorized use. Following Magubane’s complaint (whose work the gallery has also exhibited), the gallery has halted the sale of Thomas’ art until the matter is resolved, Goodman Gallery said in an emailed statement to Quartz.

Willis’ work specifically deals with “representing photographic ideas through unconventional materials.” With History Doesn’t Laugh (first exhibited in 2014)he dug through the South African historical archive specifically to examine the country’s past through this lens.

In one work, titled The People Shall Govern, Thomas uses the colors and symbols associated with the African National Congress while the title is reminiscent of the party’s founding principles. In another, An injury to one is an injury to all, Willis draws on the flag of the trade union federation Cosatu. An installation Freedom in our lifetime makes use of traditional Ndebele patterns, while another is inspired by the flag of the militant Afrikaner rightwing movement the AWB.

Thomas’ other work has explored similar archives and symbols of the African American experience. Still, his use of African imagery and symbols evokes uncomfortable questions about the power dynamic between African and African American artists, similar to when rapper Kendrick Lamar’s music video for his Black Panther hit “All The Stars” allegedly borrowed from British Liberian artist Lina Iris Viktor, without her permission resulting in a lawsuit.

While Thomas has easier access to the international art economy, one can’t assume that there are “given and known power relations” between and African American contemporary artist and an apartheid-era black South African photographer—it’s important to look at this debate in context says art history scholar and writer Setumo-Thebe Mohlomi.

“At the same time, we can’t ignore that sub-Saharan Africa, and in particular South Africa, have become places where visual arts work is very sought after by international buyers,” Mohlomi told Quartz.

The ensuing controversy should force South African artists and photographers to ask if they’re doing enough to protect their own visual archive, rather than allowing it to become an unexamined, potentially forgotten monolith. The original photographs were themselves acts of free speech during apartheid. That rich trove of imagery could be fertile ground for international players with selfish intentions, he warns.

“I think had [Thomas’ images] been more speculative, more nuanced, to some extent tipped a hat to those in the know we would be having a completely different conversation,” he said.