Young people running for office in Nigeria have goodwill and the law on their side—but it’s not enough

In 18 months, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez went from being a bartender and political upstart in New York to being a United States congresswoman. Her journey entailed beating out a veteran heavyweight in the Democratic Party primaries despite being outspent.

In 18 months, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez went from being a bartender and political upstart in New York to being a United States congresswoman. Her journey entailed beating out a veteran heavyweight in the Democratic Party primaries despite being outspent.

In Nigeria, such a transformation is extremely unlikely for young aspirants despite recent progress in lowering age limits for political offices.

The reduction came after months of the “Not Too Young To Run” campaign led by a coalition of youth advocacy groups. It reflected the general population’s appetite for younger leaders as a 2017 survey showed a majority of Nigerians hope to elect a president younger than 50 this year. Both presidential candidates Muhammadu Buhari and Atiku Abubakar are in their 70s in country with a median age around 18.

But while young Nigerians seeking office have new laws on their side, the challenges of old remain the same.

Running for office often means going up against experienced establishment politicians with more resources, wider party structure and better name recognition—an important factor in a country where popularity rather than policy views win votes.

The limitations of spending and reach shapes young politicians’ choices from the onset: a majority tend to run for legislative offices at state and federal level as they involve cheaper campaigns focused on a smaller bloc of voters.

“Funding is a major challenge with young candidates across board,” says Rinsola Abiola, who’s contesting to become a federal legislator under Action Democratic Party. “We don’t have the kind of resources that the older generation does and politics here is notoriously expensive.” Much of the campaign-related expenses are rooted in the culture of vote buying, on the campaign trail and on election day, which sees politicians offer food and money as incentives for votes.

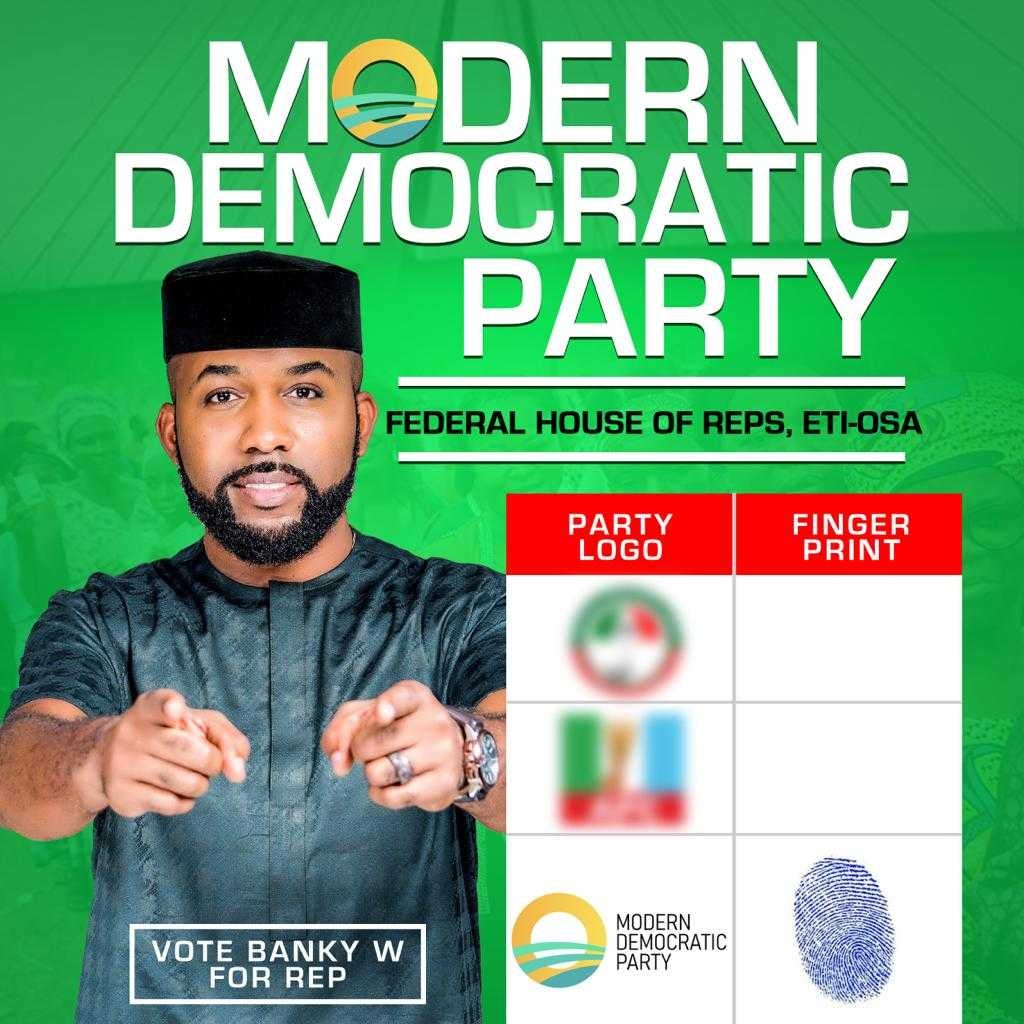

Without similarly deep pockets, most young candidates are bootstrapping their campaigns, relying on crowdfunding from supporters, leveraging social media and, in some cases, public profiles. For instance, Bankole Wellington, 37, better known as Banky W, a veteran of Nigeria’s booming music industry and a Nollywood star in two of its biggest movies, is running to become a federal legislator under the Modern Democratic Party. He has canvassed support through the help of other entertainers and a free concert.

In Abiola’s case, she has a strong political heritage: she’s the daughter of the late M.K.O Abiola, widely believed to be winner of the 1993 presidential election annulled by a military government. (M.K.O Abiola challenged the annulment of the election and died in detention five years later.)

Recognizing the major challenge that a lack of funding represents, Jude Feranmi, 27, founded Raising New Voices (RNV), an advocacy group focused on backing young candidates seeking office. Feranmi himself unsuccessfully ran for office during local government elections last year. RNV raises funds through donations and supports young candidates across various parties, providing them with campaign souvenirs.

Going this route and backing young aspirants, Feranmi argues, is one way to changed the “flawed narrative” that young candidates cannot win elections. In the long-term, part of “playing the long game,” he says, is to enable a bulk of young people get into office, create track records and gain crucial experience for when they seek higher positions. The group is supporting 25 candidates—all younger than 35—in the current election cycle.

Breaking the hold

The dominance of two major parties—the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) of Buhari and the opposition People’s Democratic Party (PDP) of Atiku—means candidates running on other platforms face an uphill battle. It’s a reality that’s true even for “third-party” presidential candidates.

But young aspirants are increasingly walking away from and being forced out of APC and PDP.

Sirajudeen Adebakin, a federal legislative aspirant under KOWA party, quit APC last year after becoming disillusioned. “It’s not possible for you to perform optimally if you belong to any of those parties,” Adebakin says. Having a campaign sponsored by party leaders and their associates translates into owing allegiances to “political godfathers,” he explains.

Abiola, also a former member of APC, says she left due to “a lack of internal democracy and dictatorial tendencies” from party leaders who threatened her so she wouldn’t run. She says condoning the intimidation would be a “betrayal” of democratic values her father fought and died for.

In some cases, the cost of winning tickets to contest on the platform of major parties is in itself a major barrier. “The nomination forms are too expensive in the leading parties,” says Jesse Nwaenyo, also an aspiring federal legislator. While purchasing a form to contest for the party ticket as a federal legislator under the major parties can cost up to $10,000, Nwaenyo’s form cost $800 under the United Progressive Party (UPP), a much smaller party.

Buying the forms under a major party also guarantees little. “Even if a young person is able to raise the said sum and purchase the form, there’s another big hurdle to cross and that’s the primaries where you’re up against more experienced politicians with bigger name recognition,” Nwaenyo says.

As such, young candidates who lose out in the primaries of major parties are known to end up in smaller parties where there’s a higher chance of winning the party’s ticket. Running under a smaller party also comes at its own price though: Nwaenyo says with UPP unable to raise enough funds through the sale of forms, his campaign has received no financial support from the party.

New methods

To differentiate themselves from older generation politicians, young campaigners are trying to do things differently. Zainab Sulaiman Umar, aspirant for the state house of assembly in Kano, northern Nigeria, under New Progressive Movement says going directly to the grassroots, making door to door visits and meeting voters in person is a tactic that could secure success on election day. Given her lack of funds like most other young aspirants, it’s also a cheaper way to campaign.

The tactic is also important as young candidates look to explore voters’ frustration with their current representatives who are seen as aloof and distant. “I go to some places and I get people telling me they’ve never seen a candidate face-to-face and engaged them this way,” Abiola tells Quartz. That disconnect and a failure to cater to the people’s needs is “a failure of governance at the smallest levels of society,” she says.

Her strategy is to “forge a relationship” with voters by “going to them where they are” rather than holding rallies and deploying surrogates as experienced politicians tend to do. “I could as well adopt the usual way of campaigning, but I want to see the people in the conditions they live in, so I understand exactly what is at stake,” she says.

But even in doing things differently, Adebakin insists it’s tough to change the deeply ingrained habit of offering cash and food as incentives for votes. “There is hunger in the land whether we want to accept it or not and it is very difficult to talk to people who are hungry to change their mindset,” he tells Quartz.

Amid the several challenges though, young candidates have one decisive upside with a majority of Nigeria’s registered 84 million registered voters aged between 18 and 35. As such, they stand a better chance of connecting with them in ways older politicians cannot.

For her part, Abiola, now in her late twenties, acknowledges her youth has been focal in helping her campaign get reception from young voters but she also concedes that being young alone does not amount to a political trump card even among that bloc of the electorate. “Being young is not enough to make people vote for me,” she says. “It’s a feature, not the entire substance of me as a person and as a candidate.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox