China’s aid to African leaders’ home regions nearly tripled after they assumed power

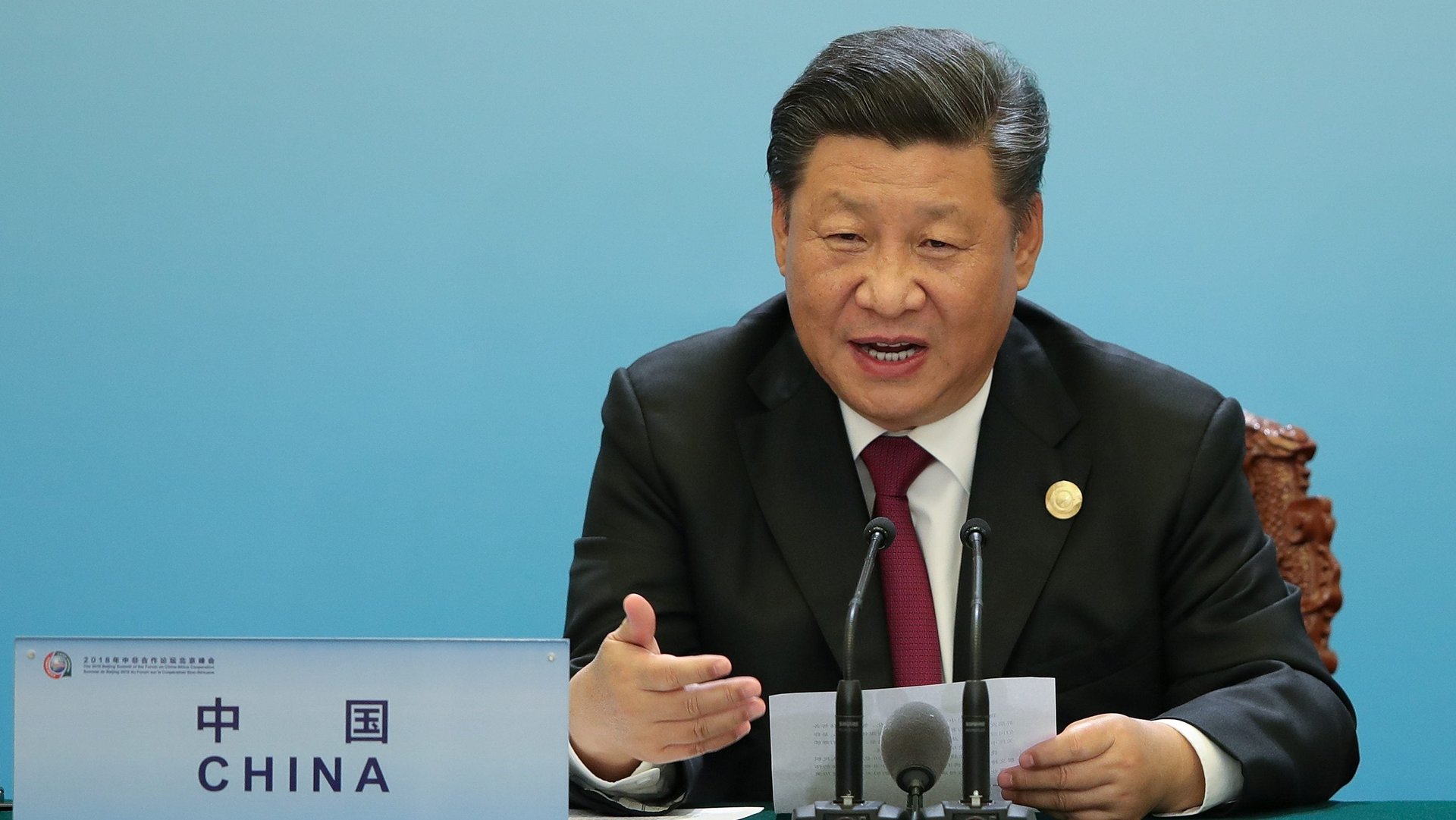

China’s aid outlay to Africa has grown rapidly over the last two decades, rising to its largest figure of $15 billion in 2018. In doling out these packages, president Xi Jinping has stressed the condition-free nature of the assistance and how Beijing wasn’t seeking “selfish political gains in investment and financing cooperation.”

China’s aid outlay to Africa has grown rapidly over the last two decades, rising to its largest figure of $15 billion in 2018. In doling out these packages, president Xi Jinping has stressed the condition-free nature of the assistance and how Beijing wasn’t seeking “selfish political gains in investment and financing cooperation.”

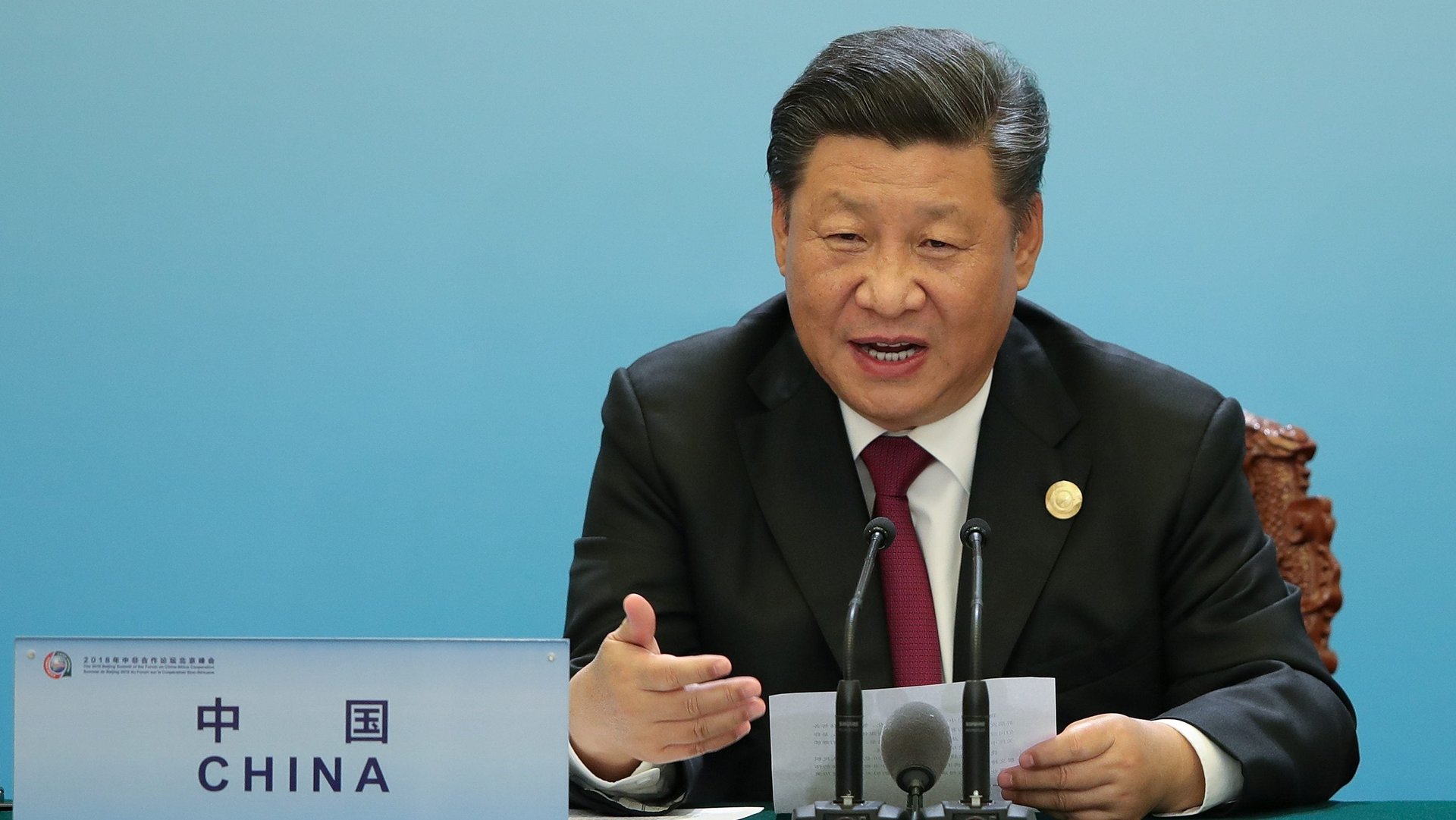

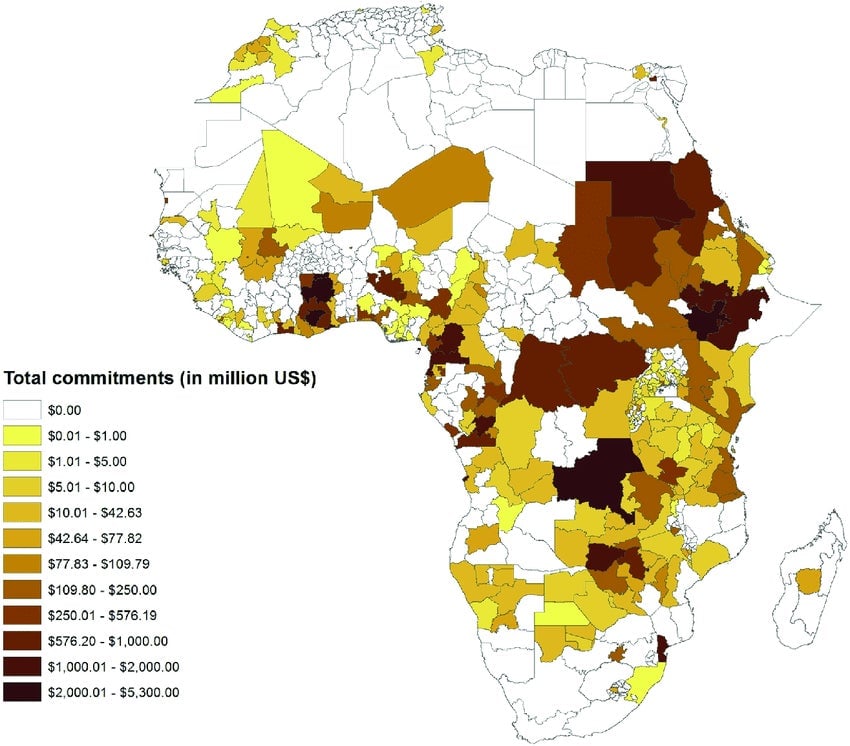

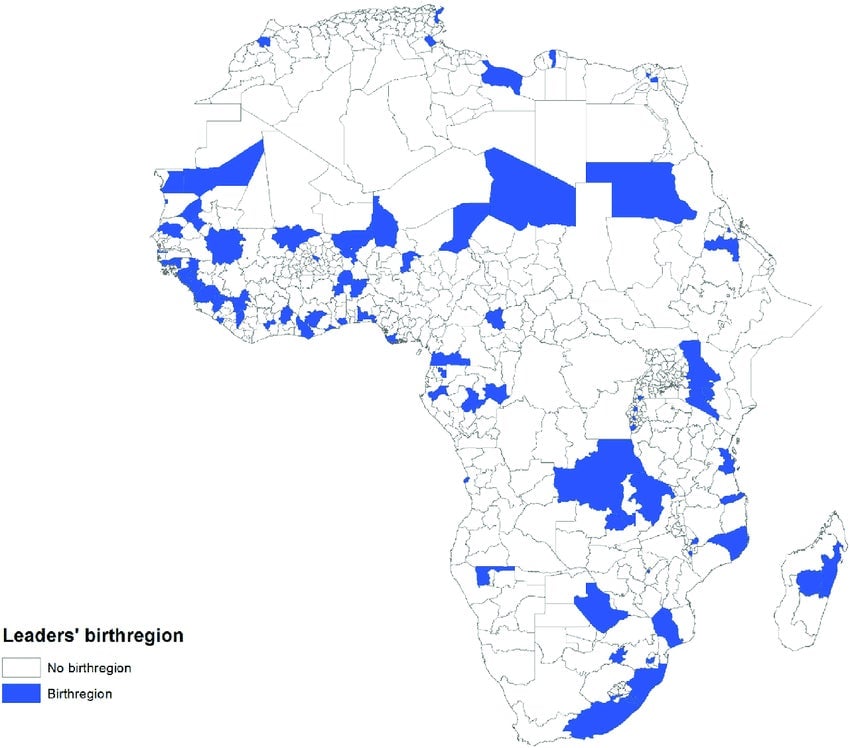

Yet foreign aid from China to Africa has proven to be political—at least on the local level—defined by narrow sectional interests and captured by state clientelism, a new study says. Published in the Journal of Development Economics, the study examined 1650 development projects done between 2000 and 2012 based on 117 African leaders’ birthplaces in 49 nations including Kenya, Ghana, Egypt, Ethiopia, South Africa, and Nigeria. The total number of projects covered was estimated at $83.3 billion.

Researchers showed the birth regions of African presidents receive nearly triple the number of aid inflows from Beijing in the years when those leaders were in power compared to other times. These incumbents also allocated significant aid to their own backyards in the year before competitive elections in a bid to “improve their chances of staying in power.” Leaders also largely distributed aid not just in their own “home districts” but also in their “home provinces” so as to maximize voter turnout in stronghold areas.

Before assuming office and after vacating it, the study noted there was no increase in Chinese aid—concluding “that these effects are causal.”

For comparative purposes, the paper looked at 533 projects worth $43.4 billion undertaken by the World Bank. The authors say they didn’t notice preferential treatment in relation to the spatial distribution of the projects, mainly because of the cost-benefit analysis and appraisal procedures demanded by the World Bank before funding is granted.

The data sheds light on the “on-demand” nature of China’s aid packages and how African leaders could abuse them for their own political gains. While both Western and Chinese aid is linked to either parties’ donor interests, Beijing doesn’t generally tie its support with improving governance and accountability, adhering to international best practices, or dealing with corruption.

And even though Xi has cautioned against “vanity projects” and said Sino-African cooperation must result in “tangible benefits,” Beijing has usually given aid to African states as long as they upheld the “One China” policy that casts Taiwan as an inalienable part of China’s territory.

This strategy of staying away from dictating African nations’ development agenda and giving them more “ownership” has garnered Beijing praise among many African states who say the “win-win” partnership was their path to genuine economic development. Last year, Tanzanian president John Magufuli praised China for giving aid “not tied to any conditions” even as his country faced aid cuts from European states and the World Bank over his government’s human rights record.

While the study focuses on China’s foreign aid to Africa, it’s equally important to note investments in infrastructure and bilateral trade has long since eclipsed aid over the past decade. Much of the focus on China-Africa relations today has shifted to concerns about mounting debt, trade deficits, and talk of neocolonialism and “debt-trap diplomacy” as China’s cultural, economic, and political foothold deepens in Africa.

And since Beijing isn’t part of global multilateral frameworks such as the Paris Club, observers have raised questions about the transparency, sustainability, and commercial viability of these Chinese state-sponsored projects.

Read more of Quartz Africa‘s China in Africa coverage here.