The “debt-trap” narrative around Chinese loans shows Africa’s weak economic diplomacy

Hugging the shores of the Indian Ocean, Kenya’s Mombasa port is one of the biggest and busiest harbors in East Africa.

Hugging the shores of the Indian Ocean, Kenya’s Mombasa port is one of the biggest and busiest harbors in East Africa.

Almost 1,800 vessels docked at the port in 2017 alone, with cargo worth over 30 million tons processed—much of it heading to neighboring or landlocked nations including Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and DR Congo. Since its opening in the mid-1890s, the seaport has developed to be a rising regional hub and a key cog in Kenya’s growing infrastructural development.

In December, reports surfaced the prized port was used as collateral for the $3.2 billion loan that was used to construct the 470-kilometer (292 miles) rail line between the seaside city and the capital Nairobi. In a leaked report linked to the auditor general’s office, Kenya was said to risk losing its port if it defaulted on the loan, with the Exim Bank of China taking over the port authority’s “escrow account” to regain revenues. Further reports have even noted it goes beyond just one asset that’s been put up as collateral and that “any state” possession was on the table in the event of a non-payment.

The revelations caused an immediate furor and triggered denials from both Chinese and Kenyan officials. China is currently Kenya’s largest bilateral creditor, and many raised questions about the mounting risks the East African nation faces as it borrows more money to fund large infrastructural projects.

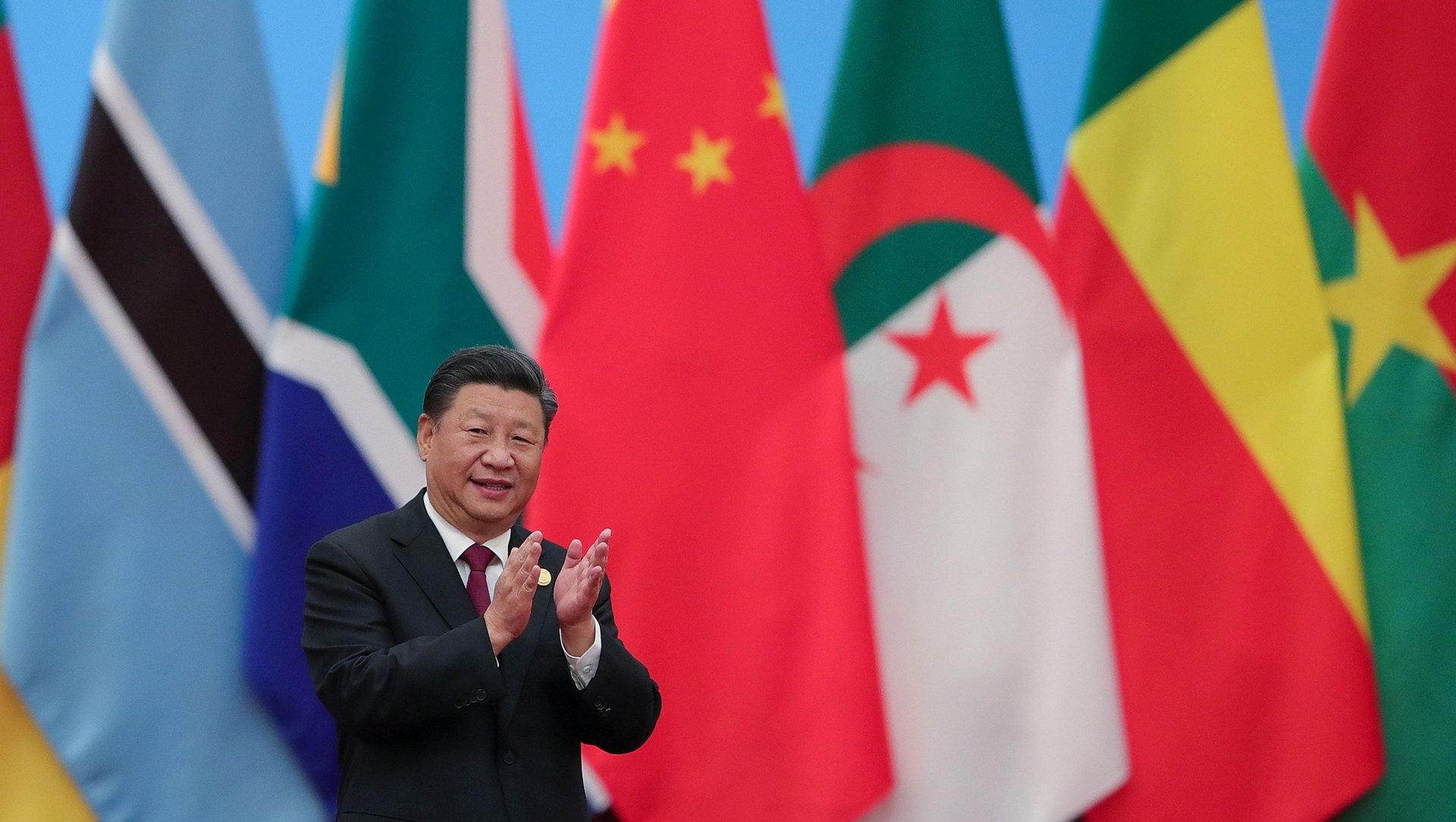

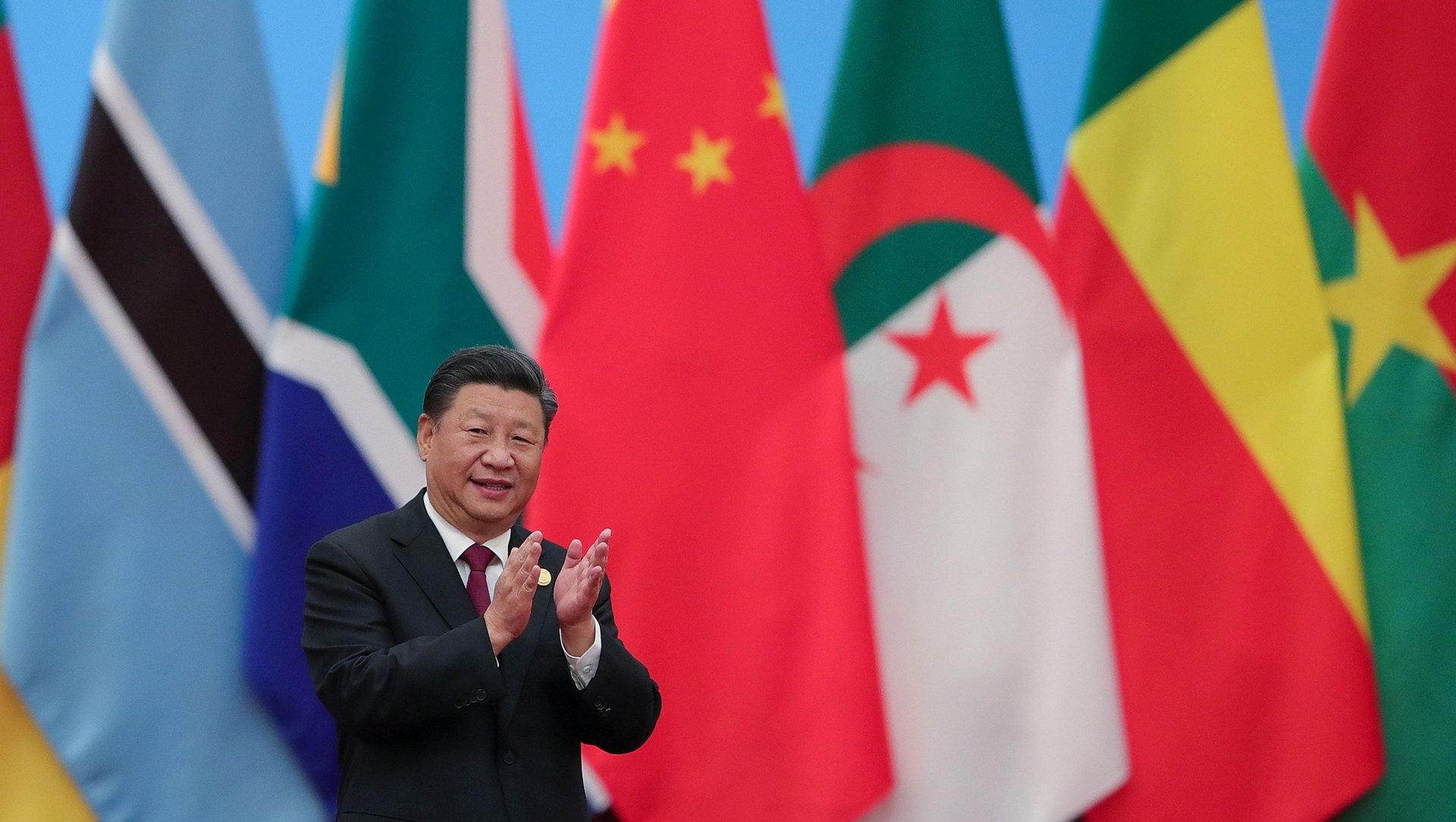

The uproar also brought to fore the issue of “debt trap diplomacy”: a term that has gained popularity in the lexicon of global geopolitics as China flexed its influence worldwide. The specter of Beijing extracting economic or political concessions from a nation unable to pay its debt obligations was first underscored in Dec. 2017, when Sri Lanka gave 70% equity and a 99-year lease for its strategic Hambantota port.

Since then, nations from Djibouti and Maldives to Laos and Pakistan have been named as facing risks of debt distress, especially in the face of the multibillion-dollar Belt and Road initiative. Last year, Beijing was also accused of taking over Zambia’s national electricity supplier and rebuilding the Mogadishu seaport in exchange for “exclusive” fishing rights along the Somali coast—allegations that proved inaccurate and that officials have refuted.

Western leaders, drawing on these examples and wary of China’s rising financial and economic might, have cautioned African states against taking out these loans. Observers have also pointed to the fact Beijing offers financing with fewer strings attached and isn’t part of the global multilateral framework for official creditors known as the Paris Club. This has raised questions about the transparency, sustainability, and commercial viability of Chinese state-sponsored lending, which has grown tenfold in the past five years in Africa.

With no officially-published contracts and “no written predictable rules” of how Beijing responds to a loan default, “people are free to speculate,” says W. Gyude Moore, a visiting fellow at the Center for Global Development. Between 2000 and early 2019, there were 85 instances when China canceled or restructured debt globally—including most recently in Cameroon.

The Sri Lanka port remains the only place in the world where Beijing took control of a state asset, with observers noting that officials understood the damages “debt book diplomacy” could bring to China. Yet Beijing’s debt relief or repayment actions, Moore notes, remains “haphazard. It’s unpredictable. There’s nothing written. It’s confusing.”

Growing Sinophobia

Chinese loans are currently not a major contributor to the debt burden in Africa; much of that is still owed to traditional lenders like the World Bank. Yet Kenyan economist Anzetse Were says the debt-trap narrative and anti-Chinese sentiment have intensified because African nations like Kenya have a fundamental problem with fiscal transparency and because the continent’s past relationship with external forces, both pre- and post-independence, was one “defined by exploitation.”

The general public, she said, remains in the dark about the deals with China. “We don’t know how much we owe; we don’t know the terms.”

Yet that shouldn’t detract from the agency of African leaders to saddle their nations with unnecessary debt, says Lina Benabdallah, assistant professor of politics at Wake Forest University in North Carolina. “The problem is not borrowing money; the problem is managing it and making sound decisions as to how to pay it back.”

The opacity surrounding Chinese deals in Africa—besides those signed with the US and Europe— also showcases, Were says, Africa’s weak economic diplomacy and its deficiency in creating institutional frameworks catering to taxpayer interests. This is especially crucial in a multipolar world where the scope of interest and engagement in Africa is widening beyond China, the EU, and the US to include Brazil, Turkey, India, Japan, and the Gulf states.

And with no capacity to effectively negotiate, Were argues “their agendas will drive our response rather than our agenda meeting them with their interest and seeing how we can both benefit.”

This is especially true of smaller nations with weak governments like Somalia, which not only faces technical and resource constraints but also the mechanisms to “ensure compliance, financial probity, and oversight,” says Rashid Abdi, the Horn of Africa project director at the International Crisis Group.

Bargaining power

Because there’s no frame of reference for Chinese deals, Moore, who previously served as Liberia’s minister of public works, says African governments can improve their capacity to negotiate by drawing support from global litigation services. These include the African Legal Support Facility hosted by the African Development Bank or pro-bono entities like the International Senior Lawyers Program. Mobilizing these resources, he adds, could improve the quality of project selection and the process of delivering them.

Growing effective at these negotiations will be crucial as China faces an economic slowdown, ballooning debt, and internal criticism on why it was spending taxpayers’ money abroad, to say nothing of the external reproach that its Africa presence is akin to neo-colonialism. The state-funded insurance firm Sinosure, for instance, recently said it lost up to $1 billion on the Addis-Djibouti railway.

Moore says that means the “validity and legitimacy” of Chinese loans will continue to be questioned if done in secret, especially if a nation is committing to an obligation for two to three decades.

“China doesn’t have to sign up to the Paris Club rules,” Moore explains. “China can write up its own rules and publish them.”

In the meantime, Were says African citizens have to agitate for and build technocratic governments that are responsive democratically. That’s “probably the biggest challenge for our generation.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox