Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly referred to the 70% debt load owed by Kenya to China as external debt. It is bilateral debt. This story was also updated to clarify the difference between bilateral debt and external debt.

Kenya’s public debt load recently surpassed the 5 trillion shillings mark ($50 billion), renewing questions over the government’s borrowing binge, how it would show the proceeds in terms of economic growth, and whether it could repay these loans in the long run.

Much of that lending has come from China in recent years, but new data shows that Kenya’s obligations to Beijing go much deeper than many ordinary Kenyans realize. China is now by far Kenya’s largest lender, accounting for 72% of bilateral debt by the end of March, according to documents from the Treasury obtained by Kenya’s Business Daily newspaper.

That is a 15-percentage point increase from 2016 when China accounted for 57% of Kenya’s bilateral debt. It is also eight times more that what it received from its next biggest lending partner, France. Bilateral debt refers to debt between nations and is part of a country’s overall external debt, which also includes debt to international organizations like the World Bank, referred to as multilateral debt. Overall, China accounts for over 21% of Kenya’s external debt.

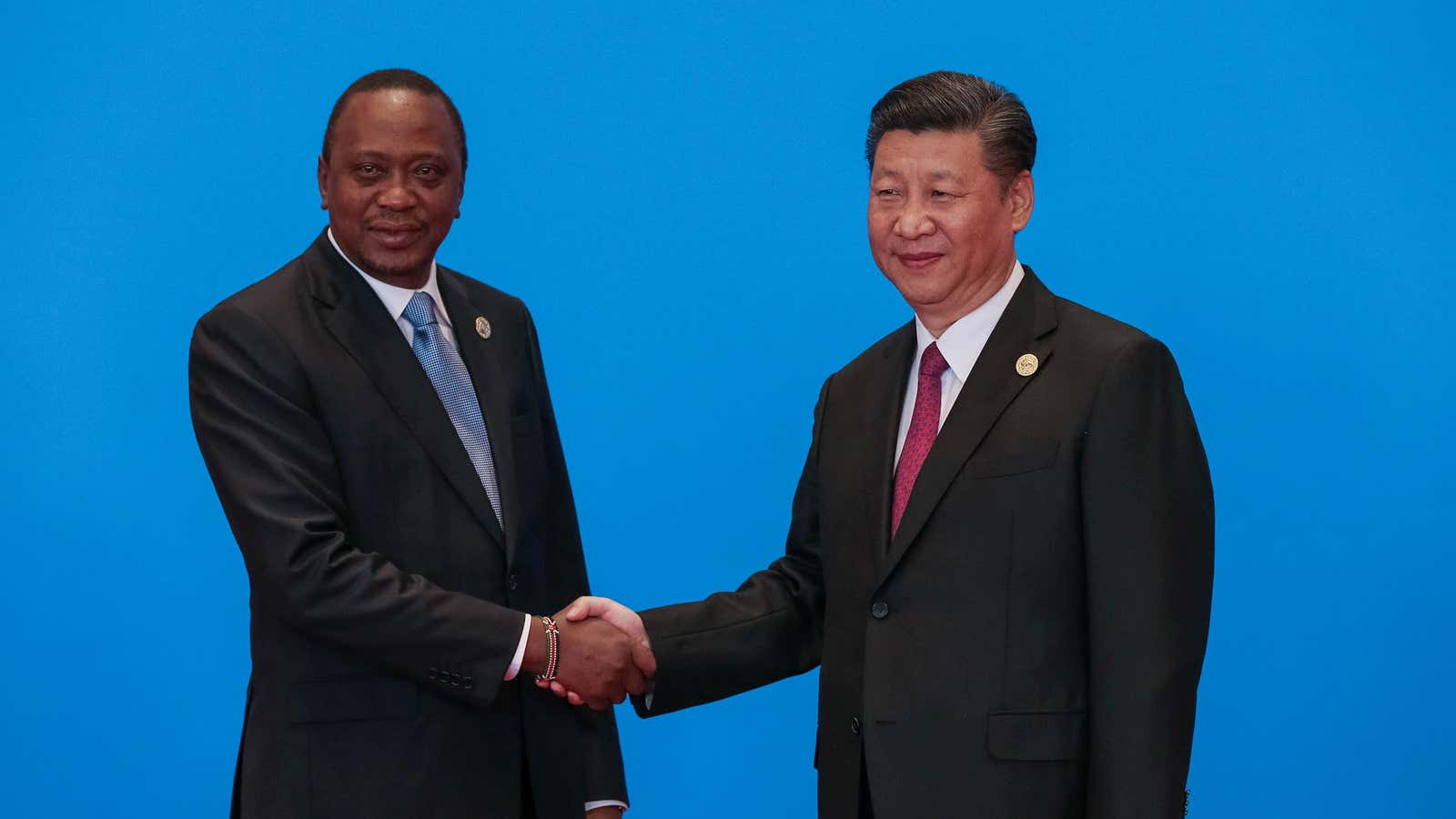

Over the last few years, officials in Nairobi have defended the borrowing spree, saying it was part of efforts to upgrade infrastructural investment, expand energy options and distribution, and improve transportation systems. The growing access to Chinese funding also points to developing Sino-Kenyan relations, with the government looking to access easy loans with fewer strings attached.

In early May, Kenya was also the latest nation to join the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, a China-led financier that offers credit by dropping the conditionality on deregulation, privatization, and reforms that come with aid from Western-led multilateral agencies like the IMF. Kenya was also one of 14 African states that recently met in the Zimbabwean capital Harare to discuss whether to hold the yuan as part of their foreign reserves—pointing to China’s growing muscle as a global financial power.

Critics, however, argue that increased lending from China will only encourage dependency and could have the potential of entrapping nations in debt. The Chinese “have become adept at colluding with cabinet secretaries and heads of parastatals into signing opaque commercial agreements that end up saddling our external debt register with expensive loans,” Jaindi Kisero, a columnist with the Kenyan paper, Daily Nation, wrote in May.

The rising debt levels in Kenya are already causing concerns globally too. In February, global rating agency Moody’s downgraded Kenya’s rating owing to rise in debt levels and deterioration in debt affordability. The International Monetary Fund also stopped Kenya’s access to a $1.5 billion standby credit facility due to non-compliance with fiscal targets. The IMF urged Kenya to lower its deficits and put the country’s debt onto a “sustainable path.” All this happens as Kenya is roiled by a spate of corruption scandals involving government officials who allegedly siphoned tens of millions of dollars from state coffers using fake tenders and suppliers.