Kenya has become the latest country to join the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the China-led financier established to fund infrastructure projects along with schemes in energy, transportation, agriculture, telecommunications, and more.

The East African nation joins two African states, namely Egypt and Ethiopia, along with a total of 86 others from six continents who have enlisted with the financial institution since it commenced operations in Jan. 2016. Kenya is yet to disclose its intentions for joining AIIB or how much capital it plans to inject as part of its required shareholding installment. But the move could be seen as part of the Kenyan government’s efforts to expand its financing options as it commits to upgrading its infrastructural network.

Joining the AIIB is also only practical, given the lender’s rise as a global institution aimed at rivaling Bretton Woods Institutions, namely the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. From the onset, AIIB was reportedly set to offer loans to emerging economies with fewer strings attached, and by dropping the conditionality on deregulation, privatization, and reforms that come with aid from the West.

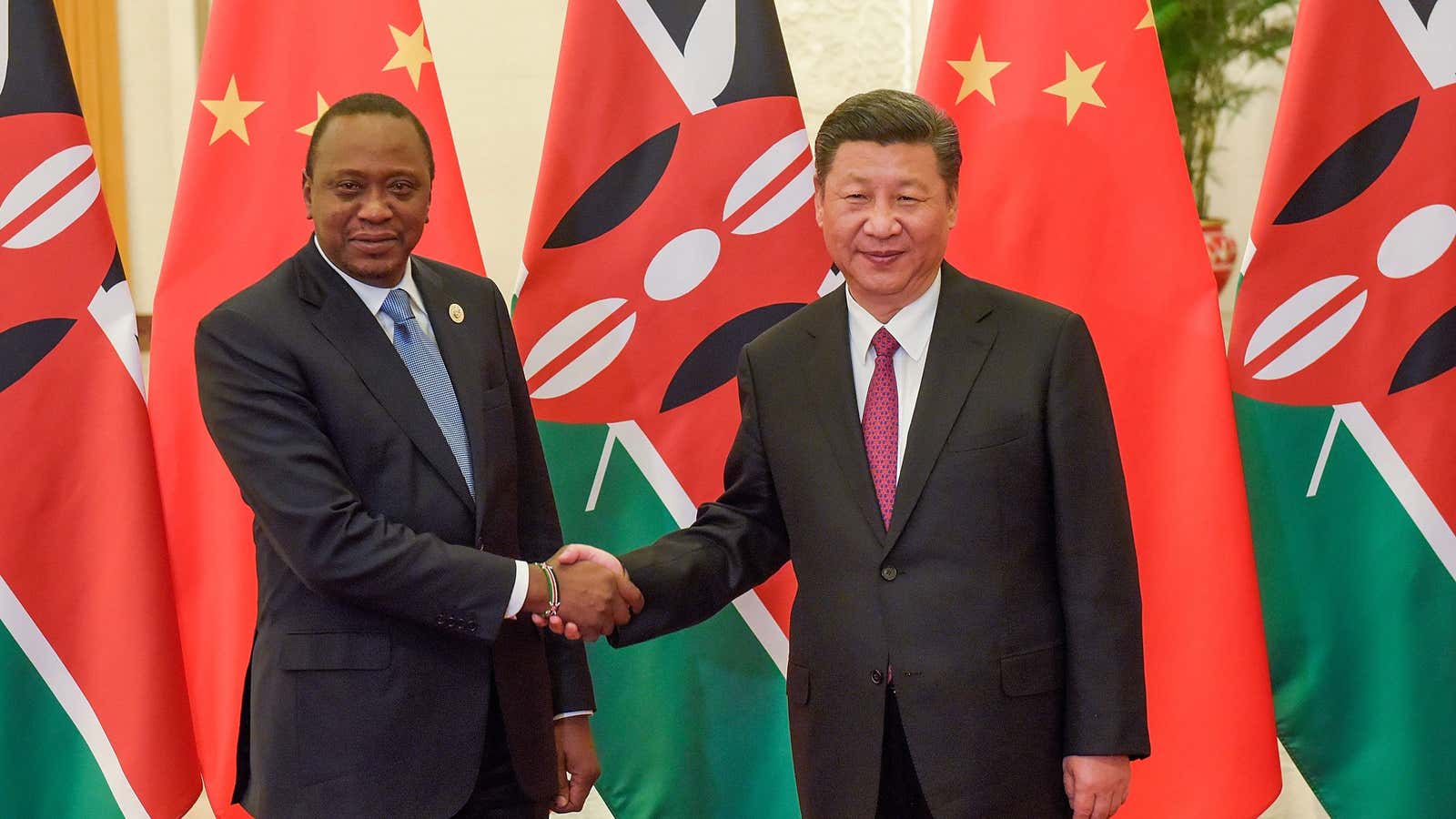

China, which is challenging the global finance order imbalance, broadened the bank’s loan portfolio and partnered with multilateral development lenders from Africa, Latin America, and the Islamic world to boost the bank’s footprint. The bank’s expansion is also indicative of China’s emergence as a greater power that is taking on more global responsibilities, especially in the isolationist post-Brexit and Trump era.

AIIB’s significance also coincides with China’s ambitious One Belt, One Road initiative, which will spend as much as $3 trillion on roads, ports, and other updates to infrastructure in more than 60 countries. For African governments, this is a substantial move, given how they have increasingly looked to China and the East for loans and a chance to expand their own economies. Both South Africa and Sudan are currently in the process of joining the AIIB.

Yet the sober assessment here is the growing risk of debt distress that African nations face as they tap international debt markets. And while corruption and poor governance are partly to blame for these debt overloads, China is often accused of practicing “debt-trap diplomacy.” This involves offering cheap and opaque loans that help it gain access to natural resources and further its own geo-strategic and diplomatic interests, while applying the sting of default if nations can’t repay their interest down.

But as African countries’ insatiable demand for investments in infrastructure and socioeconomic development grows, the role of institutions like the AIIB will only come under more scrutiny. This is especially true in Kenya where China is now the country’s largest bilateral lender amassing more than 66% of outstanding debt in 2017 ahead of institutions like the IMF.

And beyond the opportunities granted by AIIB, economist and development analyst Anzetse Were says Kenya joining the bank might “mask our indebtedness to China” since the new loans will be listed as multilateral loans and not bilateral. “The tracking will be a bit more difficult,” she said.