Photos: Kenya is struggling to make commercial sense of its flagship Chinese-built railway

When Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway leaves the terminus in the coastal city of Mombasa, it pulsates north, passing through towns and over picturesque national parks to reach its final destination in the capital city of Nairobi.

When Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway leaves the terminus in the coastal city of Mombasa, it pulsates north, passing through towns and over picturesque national parks to reach its final destination in the capital city of Nairobi.

The 472-kilometer (293 miles) rail line was completed in 2017 to the tune of $3.2 billion and is considered Kenya’s largest infrastructure project since independence in 1963. The SGR was constructed to replace the “Lunatic Express,” the Kenya-Uganda meter-gauge railway line that was completed by British colonial forces at the beginning of the 20th century.

More than 100 years after the building of the earlier colonial railway, the modern line is emblematic of the new rising power in the region: China. In the past two decades, Beijing has become the go-to financier for African countries looking to fill the gap of much-needed infrastructural projects aimed at boosting trade, investment, and economic growth.

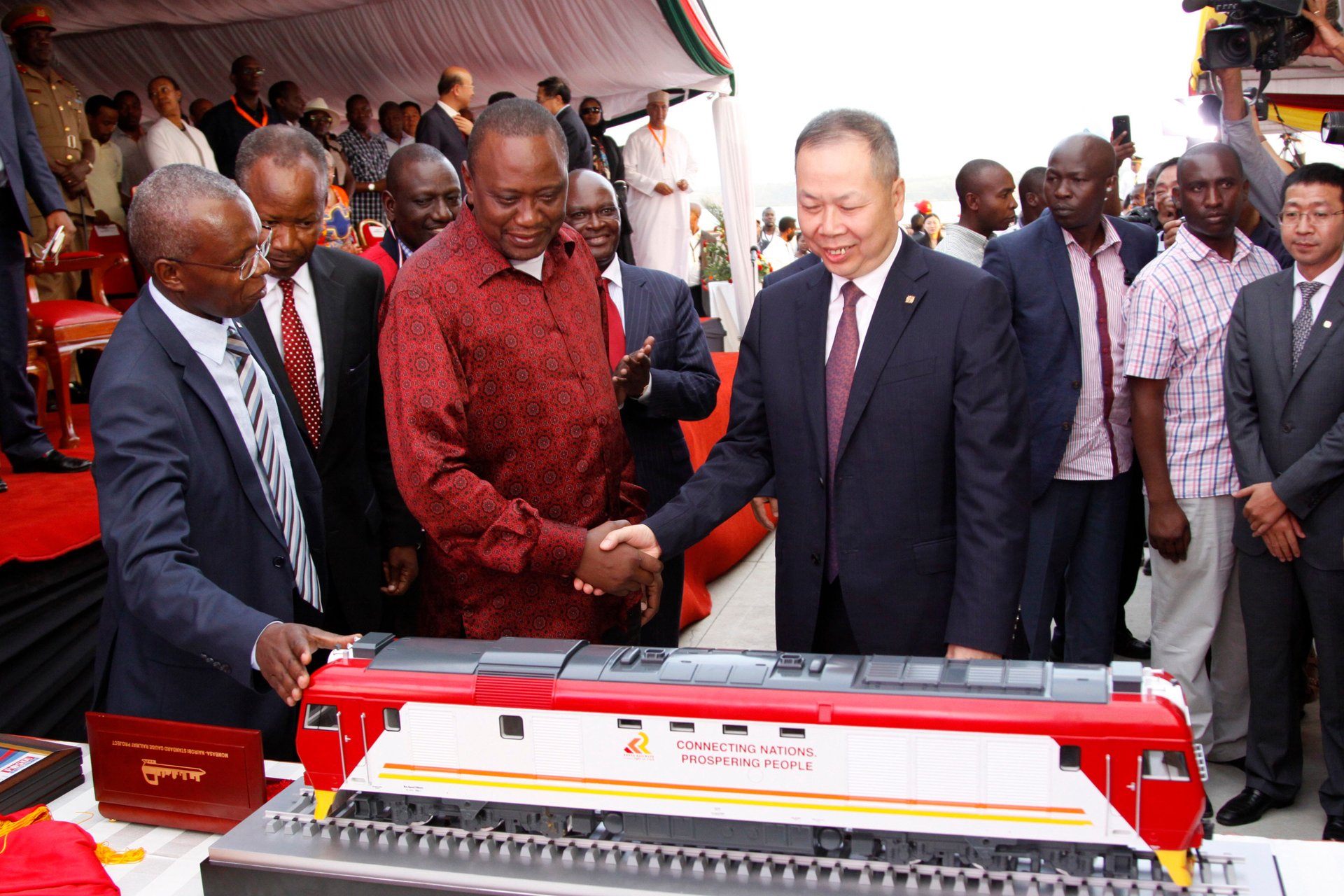

Kenya’s new railway is no exception: largely financed by the Export Import Bank of China, it was developed by China Road and Bridge Corporation and is operated by China Communications Construction Company. With the completion of the first Mombasa-Nairobi leg, the subsequent phases of the project seek to connect land-locked nations including Uganda, Rwanda, South Sudan, and Ethiopia to the Indian Ocean.

Yet those grand ambitions have now come to a halt, as the rail’s fresh tracks end in the sleepy town of Duka Moja about 70 miles southwest of Nairobi. Revelations about the troubling nature of the project surfaced earlier this year after president Uhuru Kenyatta failed to secure the financing needed from Beijing to complete the line. Both Chinese and Kenyan officials later denied the SGR’s extension to western Kenya was ever part of the deal and lambasted media reports suggesting otherwise for being inaccurate and misleading.

The funding limitations now preclude the full completion of one of China’s biggest infrastructural ventures in Africa, a key cog in Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative. It also curbs Kenya’s aspirations to become the center of an East African rail network.

But more importantly, the controversy around the SGR has raised questions about its viability and pricing, and whether it was a massive white elephant project. China’s new-found parsimoniousness also comes as it preaches against “vanity” projects amid global criticism that its lending practices were entrapping poor states in debt. China is Kenya’s biggest bilateral creditor, and Beijing’s hesitancy over the SGR has brought into question whether its big infrastructural investments would yield benefits for it now or in the future and if countries like Kenya can maintain or run them profitably.

The SGR “wasn’t something that was valuable for the people of Kenya,” says Kenyan anti-corruption czar John Githongo. “Right now, all the data and statistics we are getting around this show that we are going to lose.”

Value for money

From Ethiopia to Sierra Leone, Algeria to Zambia, China-backed projects are increasingly becoming instructive of the benefits—and pitfalls—of taking in Chinese loans. When the standard gauge railway was first approved in 2012, it was advertised as a scheme that would reduce Kenya’s logistics costs by 40% and grow the economy by 1.5%.

Authorities said the line would create jobs, decongest the port of Mombasa, reduce road wear and tear, and lessen environmental degradation given the fewer carbon emissions from trains. Many also noted the ability of the line to boost domestic tourism since it would cut the trip from Nairobi to Mombasa’s beaches to just over four hours compared to eight by bus.

Yet from the beginning, prominent economists like David Ndii criticized plans for the new railway saying it didn’t make commercial sense. For instance, Kenya’s diesel-powered train cost just $200 million less than the $3.4 billion the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway cost Ethiopia, which is electrified, and hence more expensive, and runs over 170 miles longer. Critics also pointed out China’s massive port developments in Djibouti, Kenya’s Lamu, and the now-stalled Bagamoyo port in Tanzania meant Mombasa would have a hard time competing for transit cargo to landlocked states including Rwanda, Uganda, and South Sudan.

Almost two years since the SGR’s launch, an official report noted that it cost twice as much to carry cargo by rail than by road. While the average transport for a 20-feet container from Mombasa to Nairobi by road was $650, it cost $1,270 to haul it by rail. While the SGR was promoted as a cheaper and faster alternative to road transportation, the report’s authors said bottlenecks such as delays in certifying and clearing goods from the port were initially not taken into consideration.

Transport officials trying to improve the situation announced in late July all cargo from Mombasa’s port will be carried inland only through the SGR. But the directive was withdrawn after protests that it would kill trucking businesses and container freight stations, not to mention clearing and forwarding enterprises.

“That the operational losses registered so far have compelled the state to use threats and intimidation to force importers to use the SGR means it has failed the suitability test,” says governance analyst Michael Orwa. “The SGR was predestined to fail, and it has not disappointed.”

Opaque contracts

The biggest controversy involving the SGR surfaced in December 2018 when leaked reports showed Kenya used its prized Mombasa port as collateral to repay the loan. In a document linked to the auditor general’s office, Kenya risked losing its port if it defaulted on the loan, with the Export Import Bank of China taking over the port authority’s “escrow account” to service the debt. Other reports noted that “any state” possession was put on the table in the event of a non-payment.

Githongo, who has blown the whistle on previous government corruption, says the secrecy shrouding these bilateral deals diminishes opportunities for public scrutiny, undermines accountability, and reinforces a culture of kickbacks. Contrary to Western leaders’ assertions, research has shown that China wasn’t willingly entrapping poor nations in debt in order to grab geostrategic assets like the Mombasa port. Yet the opacity, Githongo says, “lends credence to those who argue that, along with other things that China has exported which we like and appreciate, they have also exported corruption.”

For China, balking at financing the SGR comes against a backdrop of mounting internal and external challenges, including an ongoing trade war with the US and criticism at home that it should use the funds spent abroad to improve Chinese lives.

Caught off guard by Beijing’s decision to withhold funds, Uganda and Kenya have opted to refurbish the old railway line—a position some experts had suggested before the SGR was underway.

To minimize losses and funding for trophy projects, Orwa says it would be prudent to introduce tighter regulation around the power of the executive in nations like Kenya to sanction borrowing. If not, scarce African resources will be deployed in areas that are “unsustainable, least productive and thus less rewarding,” he says.

This way, China’s state-owned enterprises might score a win. But in the long run, “African citizens—not rent-seeking political elites—are more likely to lose.”