Digital lending apps are coming under scrutiny in East Africa for predatory practices

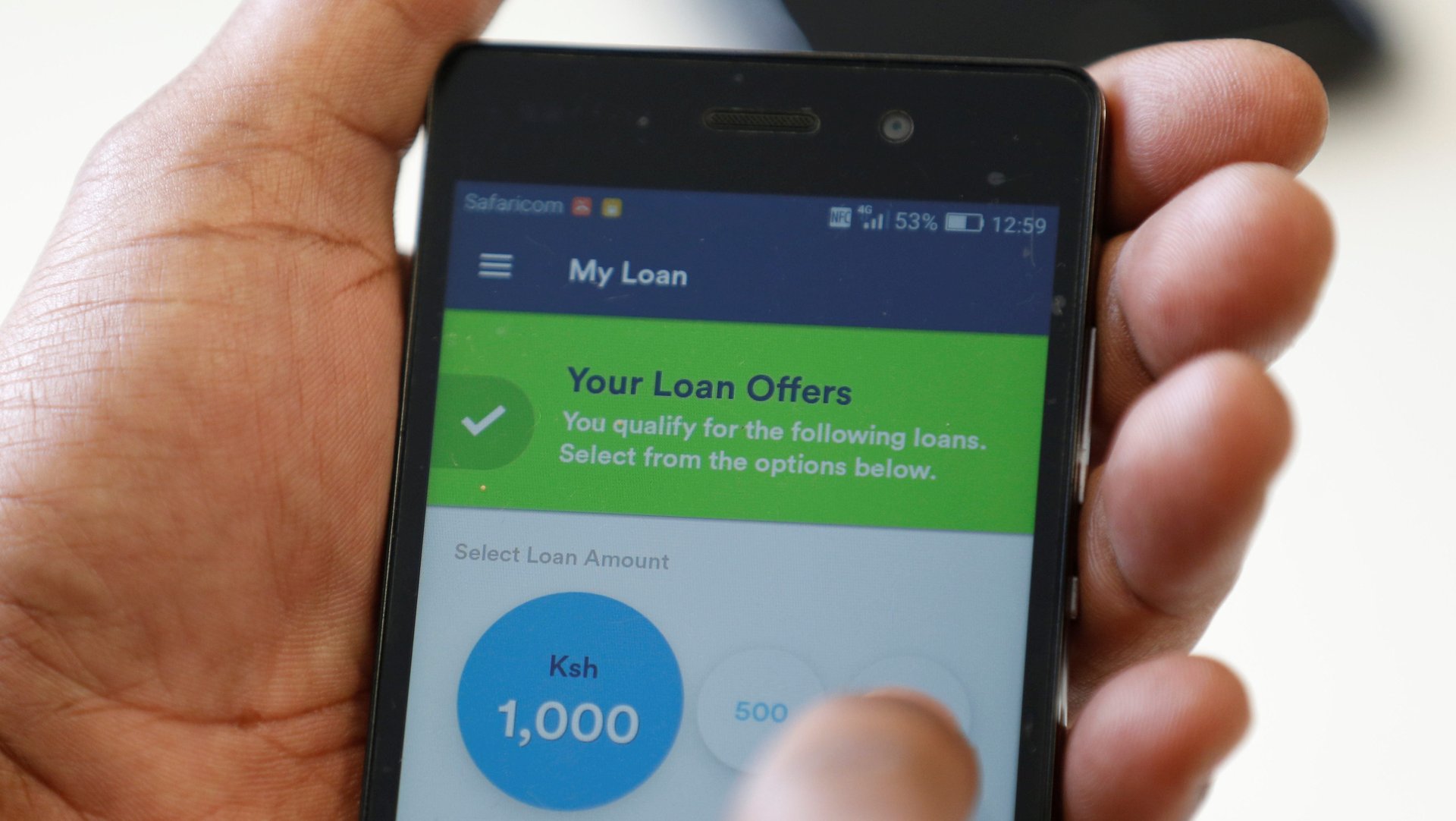

The uptake of digital lending has been on the rise across Kenya, boosted by growing smartphone adoption and the availability of mobile money transfer systems like M-Pesa. With quick application turnaround, digital credit has helped borrowers pay for basic necessities like food and rent and access working capital for their enterprises.

The uptake of digital lending has been on the rise across Kenya, boosted by growing smartphone adoption and the availability of mobile money transfer systems like M-Pesa. With quick application turnaround, digital credit has helped borrowers pay for basic necessities like food and rent and access working capital for their enterprises.

Yet increasingly, digital lending in Kenya—and across East Africa—has come under scrutiny, criticized as a “catastrophic” industry that’s pushing tens of thousands of users into debt, while commodifying their data and gaining profits from their woes.

The latest challenge comes from Google, which has updated its app store developer policies to curb predatory lending practices. In late August, the company announced it will not allow apps that promote personal loans which require repayment in full in two months or less from the date the loan was issued. The move has heralded an uncertain future for many lenders who say they don’t understand if the rules apply to them or firms only operating in the United States.

The policy could greatly impact clients of lending apps in Kenya, many of whom use Android phones. Analysis from the web firm SimilarWeb shows four out of the top 10 free mobile applications on Android in Kenya were financial apps offering loans. These included both Tala and Branch, two California-headquartered firms that have made significant inroads into the region over the past few years.

In early September, Tala, which had just raised $110 million in Series D venture funding, announced on Twitter it would no longer offer loans in Tanzania. There may be more market adjustments to come from others in the space.

In total, there were at least 49 lending platforms in Kenya as per one count last year, including Safaricom’s M-Shwari loan service.

As the digital lending industry ballooned, experts have pointed out that customers were usually confused about loan terms and conditions, hindering fintech firms’ potential to advance financial inclusion. This has seen officials. including Central Bank of Kenya governor Patrick Njoroge, criticize these platforms, saying in May they were “displaying shylock-like behavior while hiding behind nice-looking applications.”

Permissive regulations have been partly to blame too with huge amounts of credit in Kenya now accessible outside the purview of state supervision. One key gap is the regulation of lending in Kenya is done through institutional form and not by activity. So given digital lenders do not accept customer deposits as banks and SACCOS do, they are not subject to the same licensing or regulations. These include huge loaning services like Fuliza, which allows cash-strapped M-Pesa customers to complete their transactions, and Okoa Jahazi, an airtime credit service with Safaricom.

And even though entities like the Digital Lenders Association of Kenya (DLAK) have moved to fill the void with self-regulation, there’s still need for government oversight, says project director of consumer protection for nonprofit Innovations for Poverty Action, Rafe Mazer.

“Voluntary industry standards still allow the bad actors to stay out of an entity like DLAK and do business as usual,” he said, adding regulation could be “implemented by an independent consumer protection agency or at least an independent department in a regulator with an expanded mandate to cover non-banks.”

Data privacy and ownership has also started to emerge as a concern with instant digital lenders. And with no data privacy law, there’s a concern from observers and civil groups that there’s little to no oversight over how Kenyan consumers’ digital footprints are mined, stored, or used. Platforms like Okash, for instance, have gone as far as to call people on the contact list of a delayed or defaulted customer in order to recover their funds.

Pricing on the platforms remains high, partly because of the repayment models of lenders and the multiple fees incurred during transfers and cash-outs. To boost transparency around transaction fees, the Competition Authority of Kenya mandated that mobile financial services providers disclose charges.

The ease of accessing mobile lending and the lack of comprehensive understanding around its risks has also meant the growth of negatively-listed users with the Credit Reference Bureau. Research from 2017 shows 2.7 million Kenyans have been negatively listed in the three years prior, with 400,000 of those listed for an amount less than $2. This has been exacerbated by the rise of gambling and sports betting in Kenya: development agency Financial Sector Deepening Kenya has revealed digital borrowers are twice as likely to engage in mobile betting.

But while the negative credit records of digital borrowers are amplified, Mazer says the bigger issue is “the much larger set of missing positive records—as most digital borrowers repay on time.” Mazer who has worked with regulators and providers on digital lending in East Africa since 2014, says many outlets wouldn’t release positive scores because they don’t want to, they aren’t required to report, or are “allowed to only report negative information if they like.”

“There should be a level playing field where all lenders must report positive data on a same-day basis, and better enforcement of reporting requirements for those currently regulated.”

As criticism leveled against digital lending platforms grows, many Kenyans are going online to praise and chastise companies instead of waiting for resolutions from more traditional sources. These “digital cries for help,” Mazer notes, are vital because they allow customers to share their experiences and hold lenders accountable. “Luckily many firms have adapted to this and offer new digital channels to resolve complaints.”

Correction: A previous version of this story mentioned that Tala was headquartered in San Francisco, California. It is headquartered in Santa Monica, California.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox