The locust WhatsApp hotline has been pinging nonstop. Farmers and herders across large swathes of rural Kenya are sending in video clips of massive swarms flying overhead, blocking the light of the sun like a Biblical plague.

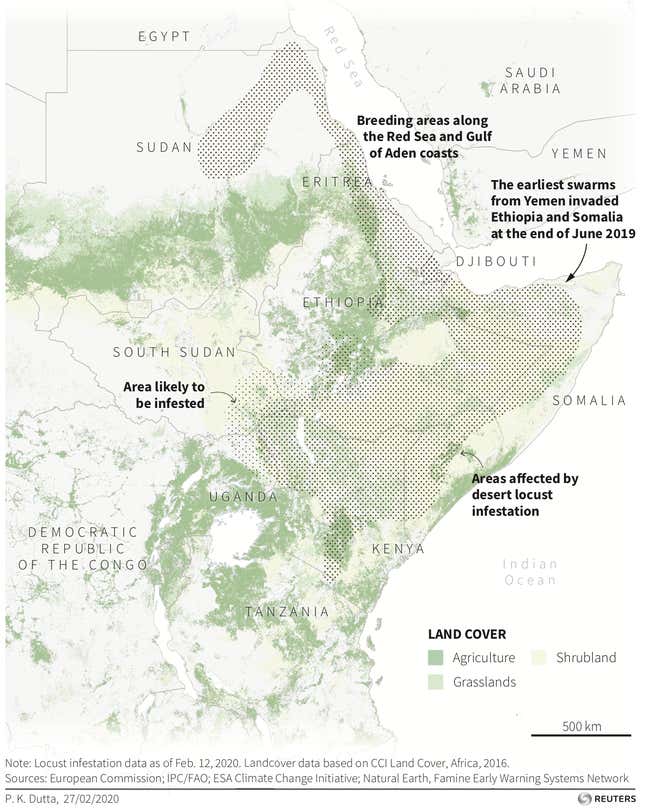

This infestation of desert locusts first arrived in East Africa last June, feeding on hundreds of thousands of hectares of crops and pastureland and chomping a path of destruction through at least eight countries (Kenya, Uganda, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia, Eritrea, Djibouti and Sudan). Scientists say these devastating insects never left East Africa: in fact, favorable wet conditions due to above average rainfall this season means they are likely to achieve two generations of new breeding by June this year, increasing their population size up to 400 times.

East Africa already has 20 million severely food insecure people, who barely eat enough to fill their stomachs each day, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UN FAO), the body responsible for overseeing the locust response. This new wave of locusts poses a serious threat to food security in a region recently devastated by conflict and climate change shocks, including extreme droughts and floods, and now anticipating a sharp rise in novel coronavirus (Covid-19) cases.

“[Farmers and pastoralists] haven’t gotten a break at all,” said Keith Cressman, UN FAO’s senior locust forecaster.

The desert locust is a winged insect that travels in swarms, consuming almost every leaf of green vegetation in its wake. A typical swarm can consist of up to 150 million locusts per square kilometer. These insects move with the wind, and can migrate as far as 150 kilometers in one day. Even a tiny, one-square-kilometer locust swarm is capable of consuming the same amount of food in one day as approximately 35,000 people.

This locust infestation originated in the Arabian Peninsula. In 2018, two cyclones dumped heavy rain on an uninhabited portion of the Arabian Peninsula, creating the ideal wet, sandy conditions the desert locusts require to breed. Three generations of breeding occurred in nine months, causing locust numbers to increase by 8,000 times and forming the original source of the East Africa upsurge that is still plaguing the region today.

The swarms leapfrogged over the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden to the Horn of Africa. In Somalia, Cyclone Pawan’s landfall in December 2019 triggered widespread flooding. Coupled with above-average vegetation due to good rains, this contributed to another dramatic increase in the pest’s numbers.

The locusts moved west and south, reaching their zenith in Kenya in the early months of this year. Experts estimate they destroyed at least 30% of the pastureland they landed on in Kenya. Here, too, abnormally heavy rains wetted the sandy soil enough to allow the females to lay new eggs in January and February.

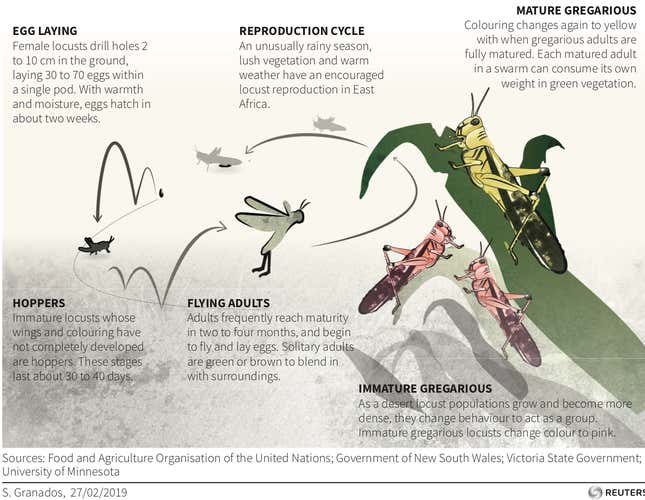

Locust eggs take just two weeks to hatch, and wingless baby locusts—referred to as nymphs or hoppers and as tiny as a pinky fingernail—cracked open their eggs on Kenyan soil during February and early March. The hoppers shed their skin multiple times, growing larger until they reach the size of a pinky finger, become adults and grow wings. They band together into devastating swarms that take flight and begin feeding on vegetation.

“That’s what’s been happening in Kenya this past month. More and more of those hoppers have become adults,” said Cressman. “So these are Made in Kenya.”

Lifecycle of a locust

These swarms are still immature, and take up to four weeks before they are ready to lay eggs. Kenya is more than halfway through this maturation cycle, and the new generation of locust swarms are expected to begin laying eggs within the week.

In Kenya, the locust maturation is coinciding with the onset of the rainy season. Farmers have been sowing crops of maize, beans, sorghum, barley and millet during March and April, in hopes that a favorable rainy season will allow for abundant growth during late April and May. With the locust swarms gaining size and strength, experts fear that up to 100% of farmers’ budding crops could be consumed, leaving some communities with nothing to harvest.

“The concern at the moment is that the desert locust will eat under-emerging plants,” said Cyril Ferrand, FAO’s resilience team leader for Eastern Africa. “This very soft, green material, biomass leaves, rangeland, is, of course, the favorite food for the desert locusts.”

FAO is working with governments and teams from non-governmental organizations to conduct massive aerial pesticide spraying campaigns throughout the region. It hopes the locusts can be controlled temporarily until southerly winds and the dry season pushes them north in June and July.

But Covid-19 poses a challenge to control activities. Disruptions to supply chains have stalled delivery of pesticide shipments, creating stockouts and shortages. Somalia is three weeks behind in receiving a shipment of biopesticides for locust control due to Covid-19 delays. Surveillance equipment, such as helicopters from South Africa, cannot reach East Africa because of lockdowns in countries where they would normally stop to refuel on their journeys north.

If control activities fail and the locusts do not move out of the region, FAO fears that up to an additional 5 million people could become food insecure in East Africa by June of this year.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox