How Mali’s security crisis and corruption allegations brought the military back to power

Mali’s president Ibrahim Boubacar Keita resigned on Aug.18 hours after he, the country’s prime minister Boubou Cissé and key cabinet members were detained by mutinous military officers.

Mali’s president Ibrahim Boubacar Keita resigned on Aug.18 hours after he, the country’s prime minister Boubou Cissé and key cabinet members were detained by mutinous military officers.

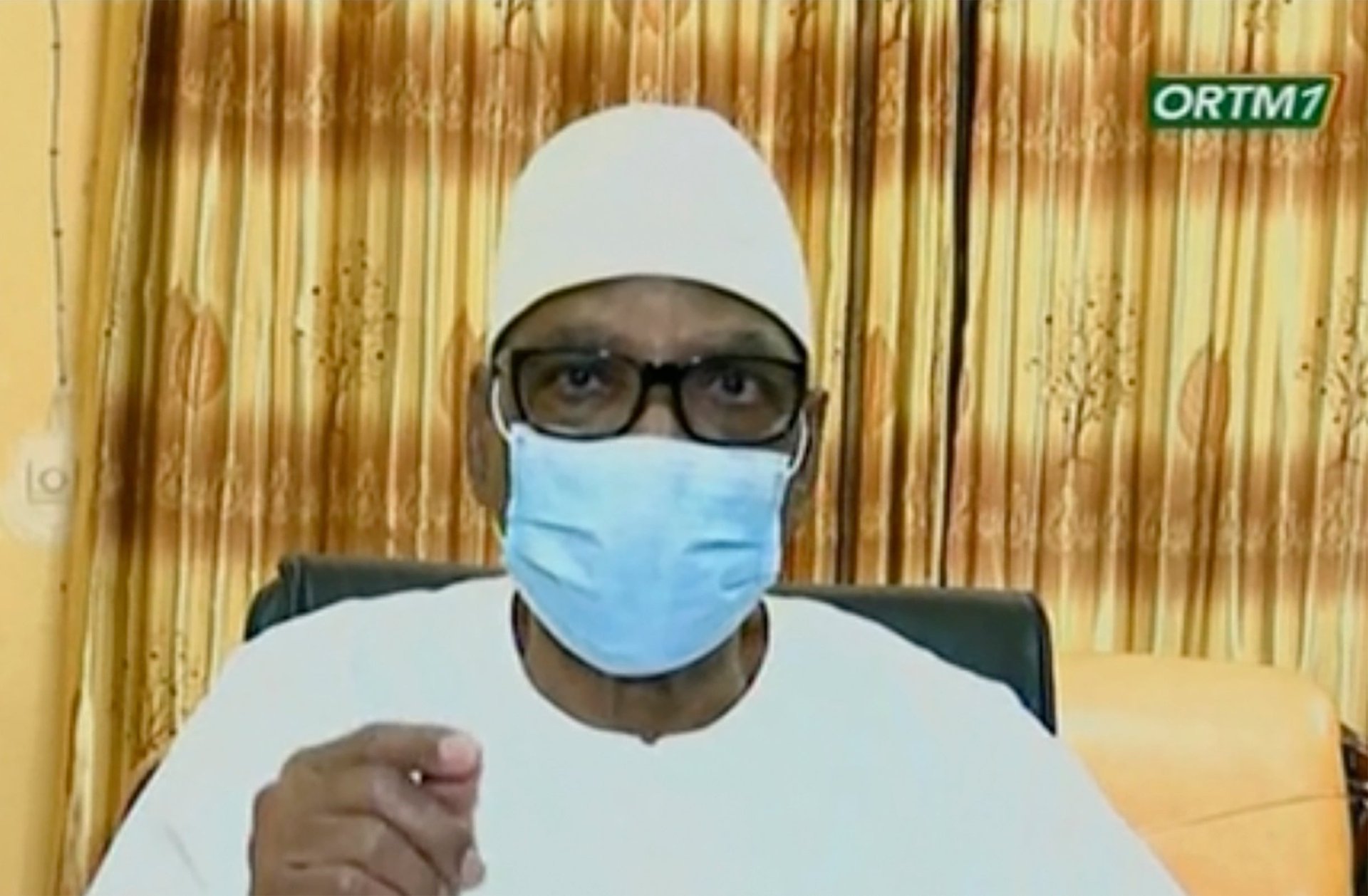

Keita announced his resignation and the dissolution of the country’s government and parliament during a national televised address while in custody at the Kati army base near Bamako, Mali’s capital. “If today it pleased some elements of our armed forces that it should end with their intervention, do I really have a choice?” said Keita. “I do not wish for any blood to be spilled to keep me in office.”

The soldiers arrested the president following months of mass protests against corruption and escalating insecurity in Mali, where Islamic militants have been active since 2012. In a broadcast on Wednesday (Aug. 19), the military announced their plans to form a civilian transitional government that will organize new elections.

Styling themselves as the “National Committee for the Salvation of the People,” the mutineers called on Mali’s civil society and political movements to join them in creating conditions for a political transition.

“We are not keen on power, but we are keen on the stability of the country, which will allow us to organize general elections to allow Mali to equip itself with strong institutions within the reasonable time limit,” said Colonel Ismael Wague, spokesman for the coup plotters.

African coups

Hundreds of anti-government protesters celebrated the mutiny in Bamako. Even though Africa has a long history of military-led coup d’etats, the numbers have dropped sharply over the last two decades. The most recent major successful military-led coups were last year’s removal of Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir from office and the overthrow of Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe in November 2017. More recently, there was an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow the ailing president Ali Bongo in Gabon last year. Since the independence movements of the 1960s, there have been at least 200 successful and failed coup attempts on the continent; between 1952 and 2012, a total of 88 military coups were successful. The regime change is often welcomed by discontented citizens desperate for new leadership which they believe will spell lasting change.

World leaders, including the African Union, condemned the coup d’etat in Mali and called for Keita’s release. The African Union has long taken a strict stance against coups on the continent. In 2000, its predecessor, the Organization of African Unity adopted the Lomé Declaration on a framework for the OAU’s response to unconstitutional changes of government. The document enumerated penalties for member states who perpetrate a coup and is reaffirmed in the current AU’s Constitutive Act which condemns and rejects such changes in power and bans perpetrators from participating in AU activities.

Regional bodies within the AU also adopt and help enforce this policy, which is why the 15-nation Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has suspended Mali’s membership, closed its member states’ borders with the country and halted financial transactions between member states and Mali. As part of its conflict prevention protocol, ECOWAS has a “zero tolerance” policy for coups and fears events in Mali will further destabilize an already volatile Sahel region, embroiled in conflict with Islamic insurgents for nearly a decade.

But there will be concern for a potential contagion effect with uncertainty around the political situation in neighboring West African countries including Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea, where both long-term presidents are running for unprecedented third terms.

Keita himself came to power in 2013 months after a military coup in March 2012 at the same Kati base toppled former president Amadou Toumani Toure. At the time, the military was frustrated with Toure’s management of the Tuareg rebellion, which had been hijacked by Islamic militants—the rebels sought to secede from Mali and create their independent state dubbed “Azawad.”

Keita promised to restore peace and order but the spate of protests preceding his ousting from office suggest a failure to do so. In June, thousands of Malians took to the streets to demand his resignation. The following month, protesters were further incensed by images allegedly showing the president’s son on a luxury yacht purportedly leading a lavish lifestyle while most of country struggled with economic hardship worsened by the coronavirus outbreak.

The Aug. 18 coup is a culmination of months of displeasure with Keita’s leadership—including jihadists’ violent interference with parliamentary elections in March—and failed ECOWAS mediation between his administration and opposition leaders.

The military has closed all air and land borders “until further notice” and imposed a national curfew. There is still no word on Keita’s future. This is the fourth coup in Mali since it gained independence from France in 1960.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox