The former headquarters of the West African Students’ Union (WASU) sits on a residential street in London’s Camden Town. The building would be easy to overlook, as it’s unadorned brickwork offers no clues to its radical past.

But from the mid-1920s until the late 50s, the WASU served as a training ground for a generation of activists— including Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, and Nigeria’s H.O Davies— who would drive the movement towards independence in their home countries. While there are 172 English Heritage blue plaques dotted around the borough, there is no signpost commemorating the WASU on any of its former London premises. Almost 100 years from its creation, there is a risk that its legacy will be forgotten.

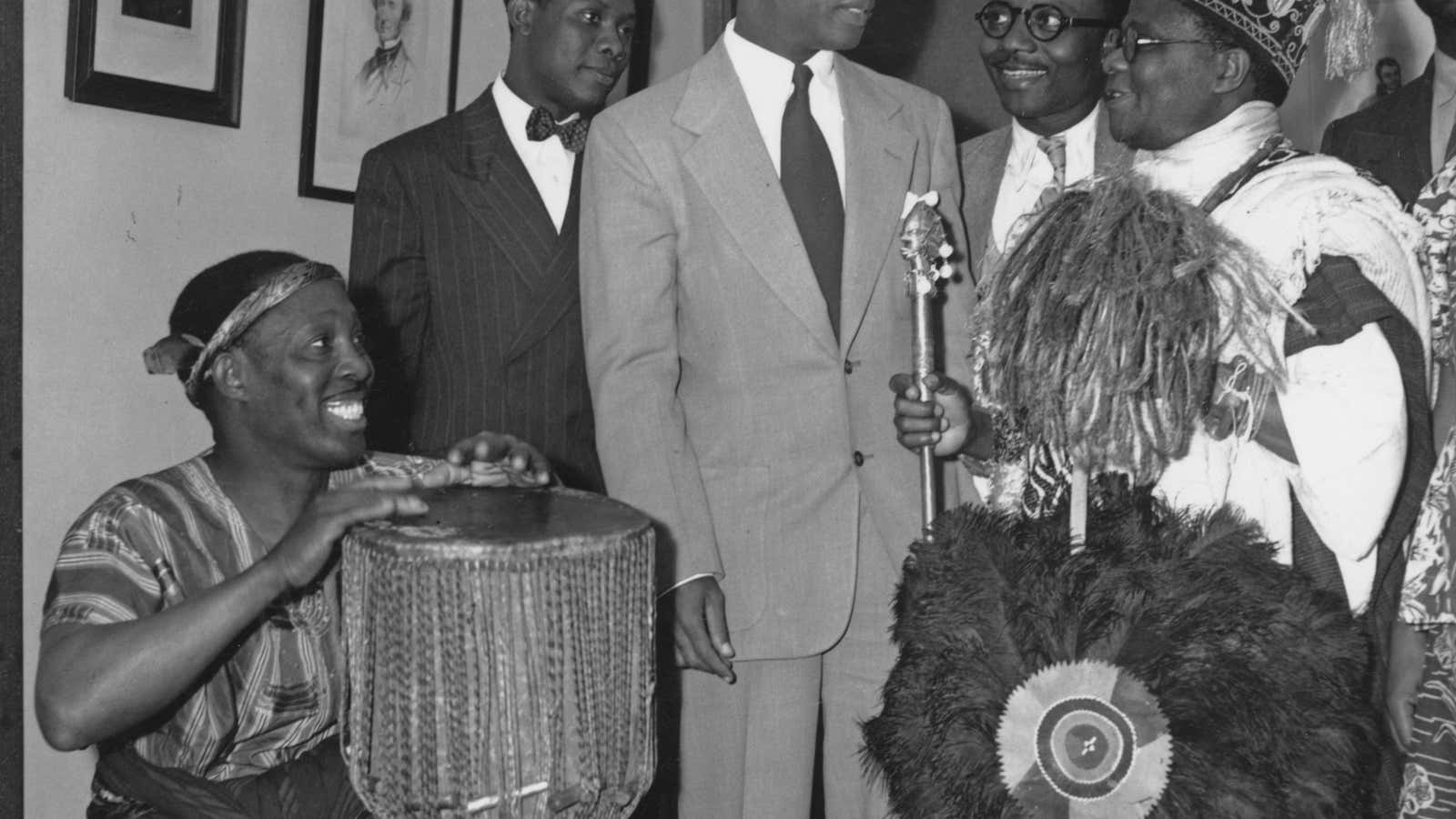

Founded in 1925 by Nigerian law student Ladipo Solanke, with the support of Sierra Leonean doctor Herbert Bankole-Bright, the WASU quickly became a kernel of anti-colonial thought and action. It united activists in diaspora with those on the continent towards a shared goal: challenging the British colonial system and the racism it engendered.

WASU created space to organize and envisage an independent future for the region, a legacy that extends far beyond the walls of its original home, creating a blueprint for global student activism today.

Facing the “color bar”

Solanke’s career as an activist and political organizer began after he successfully launched a public complaint against the 1924 Empire Exhibition in Wembley. Designed to boost morale after World War I, the £20 million exhibition showcased the scale of the British Empire, and the “exotic” cultures it contained. A highly popular event, it attracted 27 million visitors over six months. One display presented a model African village, with west Africans on display as curios. Offensive press coverage of the village implied these participants were “cannibals,” sparking outrage among Solanke and his peers.

As a representative of the Union of Students’ of African Descent, a precursor to the WASU, Solanke protested against this willful misrepresentation of African people and their customs. In a series of letters, he reminded the colonial authorities that countries like Nigeria had contributed thousands of pounds to an event where African cultures were, in his words, routinely held up to “public ridicule.” His complaint gained enough support to secure the closure of “the African Village” for the remainder of the season.

The racism encountered at the exhibition reflected an ongoing reality for African students in Britain at the time. Most of these students came from elite families, and had received a European education in their home countries to train them for positions in the colonial administration. Their familiarity with British culture jarred with the hostile reception they received on arrival, where they were frequently barred from accommodation or abused in the streets – experiences that became known as “the color bar”. This wave of students had come of age in an intellectual climate shaped by an emerging pan-African consciousness. Fundamentally, they did not see themselves as inferior to the colonial powers, and expected to take the reins of government when they returned home.

In this atmosphere, Bankole-Bright and Solanke launched the WASU to foster unity and fight for greater access to rights and opportunities. A donation from Jamaican political activist Marcus Garvey, who supported the students’ pan-Africanist ideals, provided the fledgling organization with its first temporary premises in 1928. Solanke spent the next four years traveling in west Africa to raise funds for the union and establish WASU branches across Britain’s west African colonies—Nigeria, the Gold Coast, Sierra Leone, and the Gambia.

A “home away from home”

In March 1933, the first WASU hostel opened on Camden Road to provide accommodation to students and visitors of African descent. At a time when white-owned establishments could legally refuse black tenants, the hostel was designed to be a “home away from home” for Africans in diaspora. Known as “Africa House,” it gave members access to meals, a library, a reading room, games room and space to welcome visitors.

Chief Opeolu Ogunbiyi, Solanke’s wife (nicknamed ‘Mama WASU’) became the matron of the hostel and organized for food to be shipped from the continent to Britain. The original building was leased from a Jewish owner, and Ogunbiyi trained a young Irish chef to cook traditional Nigerian meals, providing a glimpse into the diaspora communities living alongside each other in interwar London.

Records from the Colonial Office suggest that there were around 125 African students at universities in Britain in 1929. By 1951, this number had risen dramatically to 2,300. Over its 30-year history, the WASU would move to a new location in Camden and open a second hostel on Chelsea Embankment due to increasing demand.

Greater expectations

Beyond catering to the students’ wellbeing, the WASU operated as a determinedly political organization, establishing a parliamentary committee of Labour MPs to help advance west African interests, and publishing a journal which sought to challenge colonial narratives about Africa and its people.

While the WASU’s original aims focused on reform within the colonial system, its vision became increasingly revolutionary. Over the course of the 1930s, its members closely observed the political shifts in Europe. Britain’s weak response to Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 strengthened the WASU’s anti-colonial position, while increased exposure to Marxist ideas drew its members further to the left.

The outbreak of war intensified their demands as colonial subjects were called to fight in a European war, under the banner of Allied propaganda promoting the right to freedom and democracy. For a new generation of Africans, this rhetoric created the expectation that such principles would surely apply to the African continent too.

By 1942, the WASU was ready to make its boldest statement to date, organizing a conference to discuss the role of the Atlantic Charter in west Africa’s future. Its members issued a memorandum to the Colonial Office demanding complete self-government for the west African colonies within five years of the end of the war, to give the “people of the Empire something to fight for.”

This represented the first formal demand for west African independence, a moment University of Chichester history professor Hakim Adi believes underlines the influence of diaspora activists on the political atmosphere back home. As part of his efforts to expose blind spots in both British and African history, Adi launched The WASU Project in 2012 to revive the legacy of the movement.

“The dominant view of Black British history tends to exclude people from the African continent and focus on people from the Caribbean. There are a lot of things that people don’t know about the history of Africans in Britain, or in Africa for that matter,” he told Quartz. “You don’t see documentaries or dramas on TV about it, and that’s problematic. In that sense it’s not widely recognied but that’s a reflection of the way that history is presented.”

Nation-building

Under the influence of a new wave of leaders, including Davies and Nkrumah, WASU became increasingly assertive. As its vice president, Nkrumah led a network of African organizations to restate the demand for self-government. Returning to the continent in 1947, Nkrumah joined Ghana’s first political party. Within a decade, he had risen to lead the country to independence, declaring Ghana Africa’s first independent nation-state.

Nkrumah’s trajectory reflects the role of the WASU as a crucible for west African nationalism in the 1940s, but also its waning influence in later years. The real frontiers for the movement towards independence were, by necessity, the colonial territories themselves. Diaspora-led organizations with a regional focus like the WASU became less influential once action was mobilized towards independence for individual nations.

By the time of Solanke’s death in 1958, WASU’s influence had clearly dwindled. Still, in the three decades before independence, the movement grew into a radical network that emboldened west African nationalists by articulating the first official demand for an end to colonial rule.