How Kiswahili tech terms are pushing for digital rights in East Africa

When the Kenyan government launched a centralized digital identity project in 2019 to store the biometric data of its nearly 50-million population, the initiative was met with massive resistance from digital rights advocates who said it raised questions over human rights, ethics, and privacy.

When the Kenyan government launched a centralized digital identity project in 2019 to store the biometric data of its nearly 50-million population, the initiative was met with massive resistance from digital rights advocates who said it raised questions over human rights, ethics, and privacy.

Among the critics of the $60 million National Integrated Identity Management System was the Kenyan researcher and political analyst Nanjala Nyabola, who was concerned with how the digital identification card issued to citizens—known as Huduma Namba (“service number”)— would harm or exclude communities that did not understand the digital landscape or their digital rights.

“During that process [of the Huduma Namba initiative], we didn’t really have the language and the tools to explain to non-specialist or non-English language speaking communities in Kenya what the implications of the initiative were,” she said in an interview with Quartz.

Nyabola was inspired to help make it possible for Kiswahili-speaking communities to articulate and defend their digital rights. With funding and support from the Stanford Digital Civil Society Fellowship, she partnered with a team of Kiswahili scholars to translate key words in technology and digital rights into the most widely spoken African language. There are over 100 million Kiswahili-speaking people in over 13 African countries and beyond. The team included representatives from the major regional dialects in Kenya and Tanzania—Kiamu, Kiunguja, and Kimvita—as well as the standard Kiswahili that is spoken in schools and universities across east Africa.

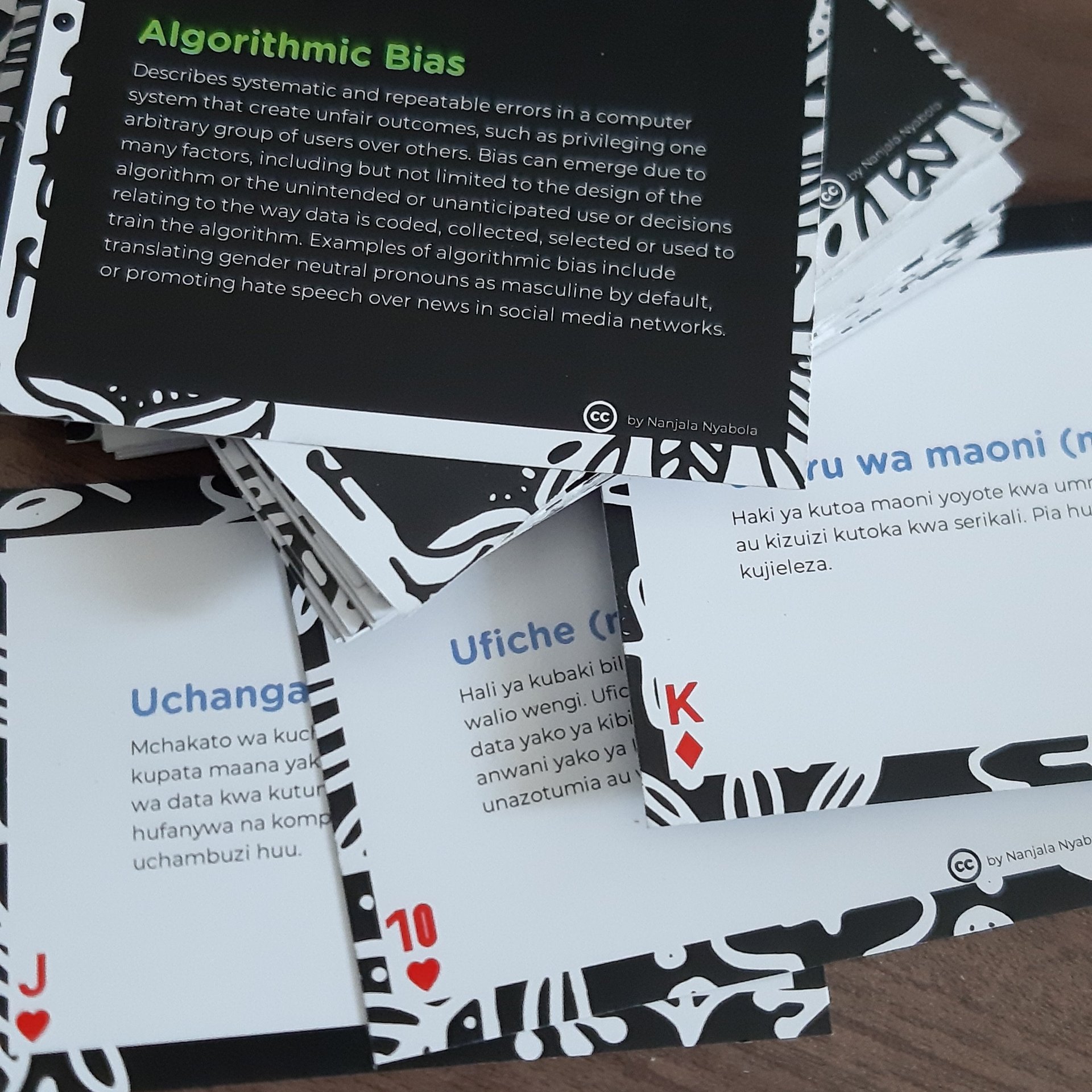

To maximize access and utilization of the new terminologies, flashcards are freely available for download online and are especially targeting university students and high school students, given that the majority of the population in Kenya is under the age of 30. The set also includes terms like “deep fakes” (Ughushi Mbizi), “trolling” (Ukeraji Mtandaoni) and “revenge pornography” (Ugono Kisasi) and is intended as a jumping off point to develop more words in Kiswahili and other Bantu family languages across Africa.

The digital divide extends to the dearth of tech terms in African languages

A published author of two novels including one on the impact of the digital age in Kenya, Digital Democracy, Analogue Politics: How the Internet Era is Transforming Politics in Kenya, Nyabola says community-led initiatives are critical in addressing the “digital divide” – a term that refers to the gap between those who are connected to and benefit from internet services and those who aren’t.

While the number of words translated so far is still small —52 as of now—they will form the foundation upon which more words in surveillance, digital rights, data protection, data privacy and more, will be built.

“English has a huge linguistic advantage in the digital age, and non-English first communities are basically playing catch up,” she said. “The gap between those who build the technology and those who use the technology is growing at breakneck speed, particularly for those who don’t speak English first or primarily. Any effort to give communities a tool they can use to speak up for their own rights is important.”

Data scientists in Africa are digitizing and formalizing African languages

African data scientists are already collaborating across the continent to advance “low resource” languages that don’t have existing databases of digital text by collecting songs, stories, prayers, and news archives. But the progress of manually gathering thousands of words to build the database is painstakingly slow, and funding opportunities are hard to come by. Nyabola is also playing a pivotal role in formalizing the use of Kiswahili in other fields including literature through the Nyabola Prize for Kiswahili fiction formerly known as the Mabati Cornell Kiswahili Prize for African Literature.

“I hope we can get to a stage where people can comfortably read and write about technology and digital rights in Kiswahili, with the same ease that we do in English,” said Nyabola. “Young people [should] know as much about digital rights as they do about online gaming and social media.”

Until now, Nyabola says that English words were filling in the gaps for words that didn’t yet exist in Kiswahili. She calls this blended vocabulary “Swanglish.”

“The problem with Swanglish is that you get the word that fits in that moment but you’re not necessarily building a lexicon,” she said. “These 52 words are a starting point so that we are doing less Swanglish and more building out of words, not just in isolation but in a linguistic context in which they are feeding and building off each other.”

A key member of the project team is Dr. Kimani Njogu, a leading linguist in the Kiswahili language teaching community. Over the course of a year, Dr. Njogu led several online workshops with Kiswahili scholars, journalists, and experts in online terminology. They began by defining an English term and then either borrowing the word and adapting it to Kiswahili or creating a new word entirely. Dr. Njogu said an important part of the process was engaging with local media outlets, local creatives and the BBC Kiswahili service to disseminate the vocabulary and feed it into everyday discourse.

“Language develops through utility. A term is only useful to the extent that it is actually utilized by people,” he said. “Getting young people to use the terms as an expression of their rights in the local language is really key for us because that’s the only way that we democratize the internet.”

While many researchers like Dr. Njogu are driven by their passion for the language and a commitment to freedom of expression and linguistic rights, he and Nyabola argue that tech companies should lead the charge in funding linguistic institutions and partnering with other local actors as they develop and deploy new technologies.

“We are quite limited in terms of the resources that we have, and the issue of development of terminology is ongoing,” said Dr. Njogu. “You need regular engagement between those in technology, those in linguistics, and those in practice to build these [terminologies] so that we are at pace with advancements in technology.”

Nyabola adds that tech companies should support local communities through the process of understanding and adapting new technologies.

“We have to focus on eliminating harm to communities that are removed from power. I want to see an internet that is truly a public good,” she said.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech, and innovation in your inbox.