Kenya’s plan to store its citizens’ DNA is facing massive resistance

Seeking to build a central identification platform, Kenya is storing the fingerprints, eyes, faces, voices, DNA, and location of its nearly 50-million population, and linking the data to everything from identity cards to access to education, health, and social services.

Seeking to build a central identification platform, Kenya is storing the fingerprints, eyes, faces, voices, DNA, and location of its nearly 50-million population, and linking the data to everything from identity cards to access to education, health, and social services.

The plan has alarmed digital advocates and civil libertarians who say it raises questions over human rights, ethics, and possible breaches of privacy.

Dubbed the National Integrated Identity Management System, the 6 billion shillings ($60 million) project will develop a unique identification number known as Huduma Namba— “service number”—for all citizens above six years of age. Foreign residents in Kenya will also have to apply for the listing system, whose pilot was rolled out in 15 of the nation’s 47 counties this week.

The single population register was initiated by president Uhuru Kenyatta’s administration in a bid to introduce what he called a single “source of truth” on personal identity in Kenya. For years, officials have facilitated the acquisition of citizenship through corrupt means and the government has reiterated the need to create a watertight system, especially in the wake of mounting terror attacks. But critics say the program will have unintended consequences including the denaturalization of millions of Kenyans, opening up the abuse of personal information by state agencies or third parties, and necessitating the surrender of personal information to access constitutionally-guaranteed services.

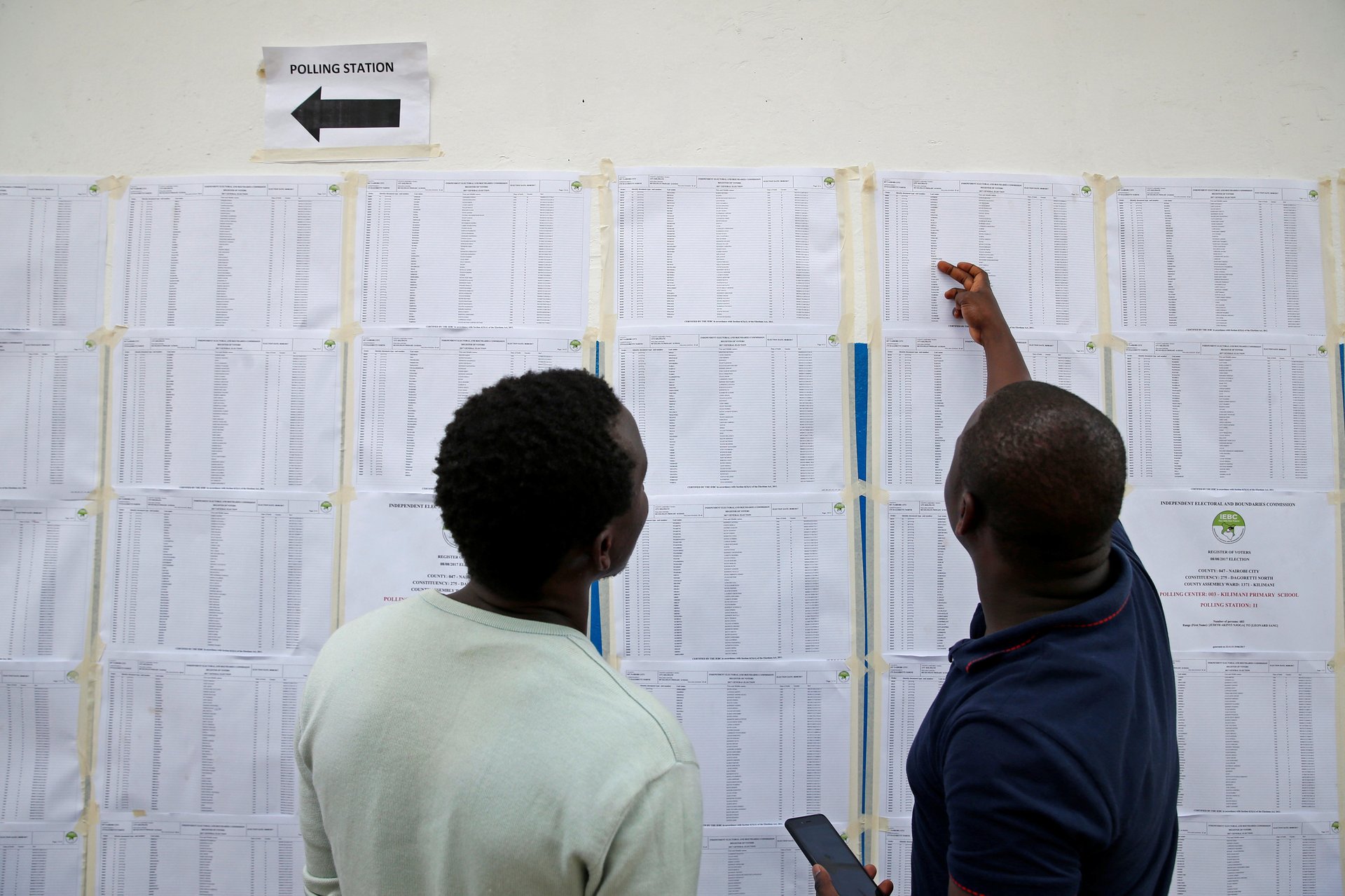

What’s more worrying, human rights lawyer Nasanga Aki says, is that the program was enacted into law without public involvement and through a “miscellaneous amendment” by parliament to the Registration of Persons Act. Such process, she said, is normally used to change minor anomalies and outdated terminologies in statute laws, not to introduce substantive programs like NIIMS. The process of awarding the registration kits was also marred by secrecy, with the tender eventually awarded to French firm Idemia, which supplied Kenya with the biometric voter gadgets that failed during the contentious 2017 polls.

Observers also say it isn’t also clear how or if there’s been a transition from the Integrated Population Registration System, the current one-stop shop for all the population data. The amendments, Nasanga says, also gives the principal secretary at the ministry of interior “wide arrays of power” especially as it relates to storage, access, and custodianship of personal data. In light of this, she argues, “My contestation is that the time is not yet right for us to have and centralize such kinds of sensitive data.”

No digital privacy policy

The effort to centralize personal data comes at a time when African governments and activists are clashing over issues including information censorship, surveillance, data retention, and internet shutdowns. The uproar over digital privacy also follows revelations that data mining company Cambridge Analytica harvested millions of Facebook profiles and worked to fix elections in Kenya and Nigeria.

The debate over NIIMS also comes as similar national biometric identity systems in countries like India and Jamaica are scrutinized for their costly and invasive nature. In a country that’s still grappling with the politicization of ethnicity, the Kenyan program presents another quandary. Officials will be using existing documents to prove and verify who is a citizen, essentially locking out people who don’t have them.

The legal gap of conclusive proof of citizenship has affected many Kenyan communities, including the Makonde, the Shona, along with pastoral communities and tribes living along the border like the Somalis.

Kenya also doesn’t have data privacy laws, and centralizing data increases the chances of breaches and leaks, says the World Wide Web Foundation’s senior policy manager, Nanjira Sambuli. Biometrics and DNA, Sambuli explained via email, are “irrevocable identifiers. In the event this data ends up in the ‘wrong hands’, it’s not something you can correct for as you would change a password.”

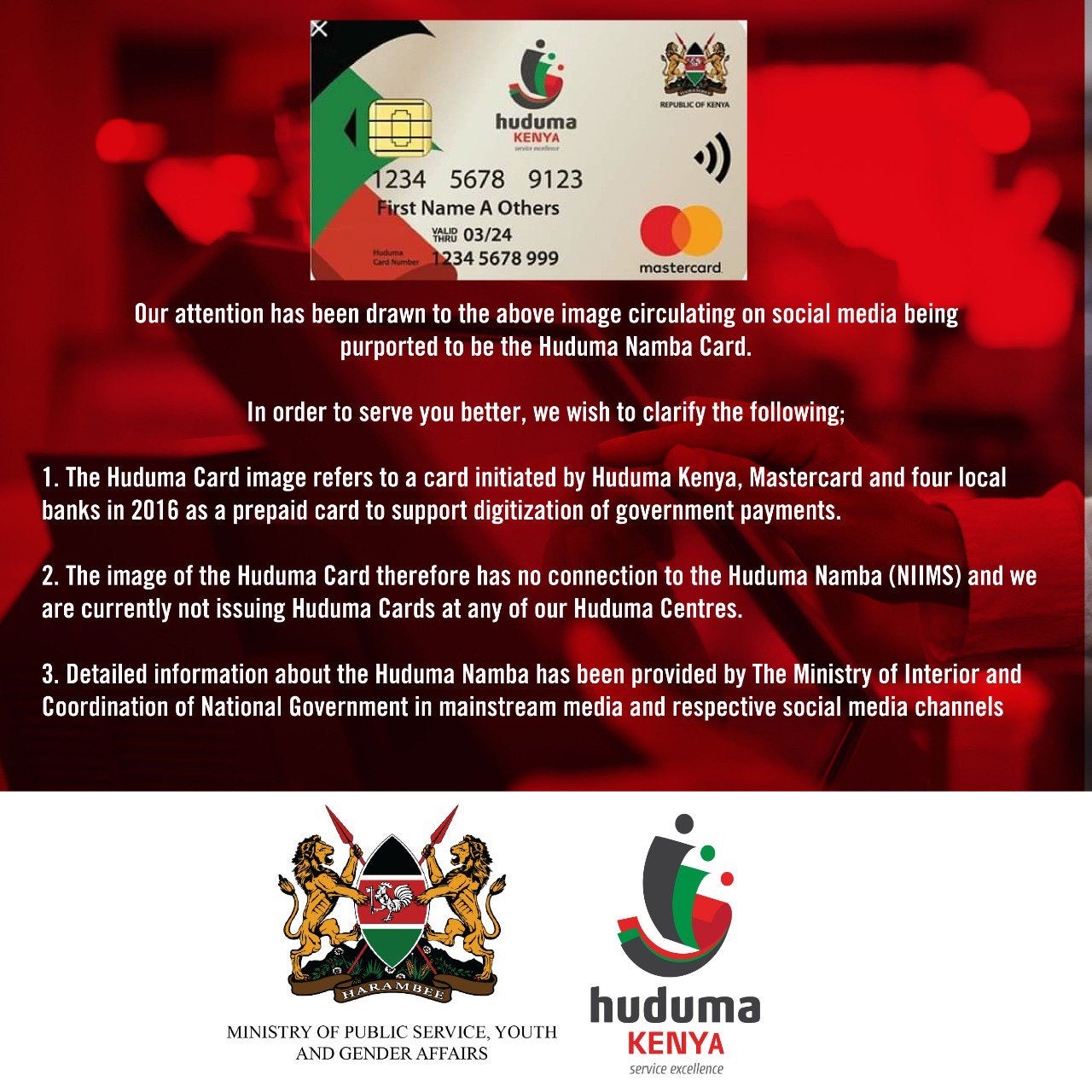

Currently, so much uncertainty surrounds the implementation of the program, which entity will host the data, how, and where. As #ResistHudumaNamba grew online, there were even claims the unique identifier codes were linked to a Mastercard-led prepaid card meant to support the digitization of government payments. Officials have since denied any link between the two, and Mastercard’s East Africa business head Adam Jones told Quartz Africa that “Huduma Namba is a completely separate initiative and one that we are not involved with.”

Yet Sambuli says “absent transparency on the terms of such contracts, we may not know for sure how data custodianship was negotiated.”

As of publication, the website of Huduma Kenya, the agency that oversees the entire process, was down.

Human rights agencies have now sued the government to halt the official roll-out, with interior officials emphasizing DNA material won’t be collected because there isn’t “a bank big enough” to store such information. Nasanga says that doesn’t allay from fears on how far the state will go to collect personal data or abuse it.

Sambuli notes there’s also need for a broader discussion around “tech determinism and solutionism” especially with regards to the public sector. If we continue “jumping on every tech bandwagon in the name of offering public services, we risk irreparably breaking societies.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox