Thomas Nguli has seen the worst of times as an ‘outsider’ in Kenya, where he was born 60 years ago. He is one of the thousands of the Makonde community that originated from Mozambique about 80 years ago but were never recognized as citizens even after several generations were born and raised in Kenya.

Until this year, they had never experienced peace of mind from the time their forefathers were brought to Kenya from the 1930s to work on sisal and sugar plantations at the country’s coast.

Kenyan-born Makonde have always been labeled as ‘outsiders’ despite not really knowing any other country than Kenya. Local officials occasionally threaten them with repatriation whenever the community kicked up a fuss to demand national identification cards (IDs). The national ID is an important document in Kenya as proof of citizenship particularly in dealings with the government and even the private sector.

“We have suffered for many years,” says Nguli. He points out there were some periods, during the presidency of Daniel Arap Moi that the Makonde weren’t even allowed to air their complaints publicly. Nguli, who has led the fight for the community’s recognition as Kenya’s 43rd ethnic group since 1995, tells Quartz. “If you dared talk at the time, you would even be apprehended.”

Whenever police cracked down on aliens in the country, the Makonde would either seek refuge in their neighbors’ homes or hide in the forest.

“We were helpless and we always felt like slaves,” Nguli says.

After Kenya attained independence from the British colonialists in 1963, the Makonde, also found in Tanzania, opted not to return to Mozambique, their motherland which was still under the rule of Portuguese colonizers (until 1975). However, Kenya’s new post-independence government did not enlist them as one of the east African country’s 40-odd ethnic groups. This meant they were ineligible for ID cards issuance. They have been living as a stateless people since then. Many of them are squatters living on abandoned plantations or on government land, for which they now want to be issued title deeds.

The lack of IDs has meant an estimated 20,000 to 40,000 Makonde are forced to live on the margins of the informal economy, unable to pursue higher education or even pay taxes without documentation.

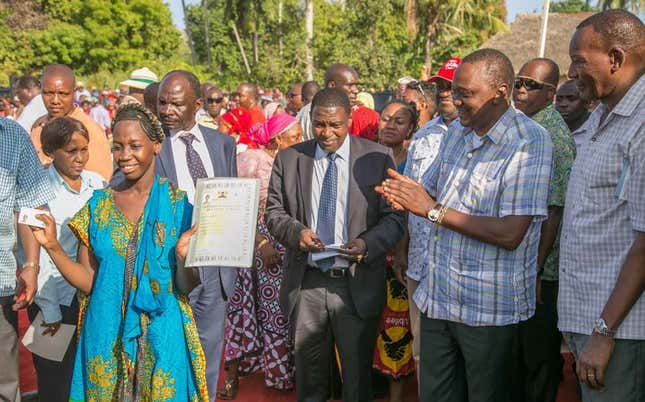

Last October, determined to get president Uhuru Kenyatta’s audience, they embarked on a four-day trek over 400 kilometers to Nairobi. Despite frustrations by officials along the way, they eventually met the president who apologized because Kenya had “taken too long to consider you as our brothers and sisters.” The long trek would mark the last time they would be referred to as stateless or aliens.

For 51-year-old Amina Kassim, a member of the Makonde community but married to a local, this may be time to start her life afresh. She, for instance, wasn’t at ease as she required a license to run her fisheries business but would not be granted the permission for lack of identification documents. This is now history.

“Life was not easy,” she says, equally recalling a time she was arrested for failing to produce an ID and had to call her husband to have her released. “But things will change now.”

But, on the day the Makonde were being given national IDs, other stateless communities in the locality wept as they stood helplessly by seeing that they were not part of the program. These were among thousands of other people born in Kenya but with origins in Rwanda, Uganda, Sudan, Zanzibar and Tanzania who also faced the same dilemma as the Makonde.

“We (the Makonde) succeeded because we always came out to explain ourselves, our history and why we needed to be fully recognized as citizens of Kenya,” Nguli points out.

Many of the problems of statelessness and pursuit for national or ethnic identity across Africa are rooted in colonial legacy. During the colonial times in the late 19th century to mid-20th century, the British, for whom Kenya was its centre for East African commerce, were responsible for moving thousands of people from their home countries to work on farms, build the railways and as soldiers in imperial wars. The status of many of these people was never resolved before the end of colonialism or soon after independence.

While many Asians came to many parts of Eastern and Southern Africa in the 1820s as merchants, the British also brought thousands of Indians to east Africa in the 1890s to build the Kenya-Uganda railway. After the completion of the railway in the early 1900s, the Indian workers opted to remain in Kenya and would later be recognized as citizens partly due to their contribution to the country’s economy. Their descendants and other immigrants from Asia are somewhat still seen as ‘foreigners’ and now want to be recognized as Kenya’s 44th ethnic group.

But, it is the voice of the Nubians, another stateless community spread in different parts of the country and across East Africa that has been as vocal as that of the Makonde. The Nubians were brought to Kenya from Sudan by the British colonialists at the end of the 1880s to fight in imperial wars. After the World War II, they settled in Kenya and elsewhere in East Africa with their pursuit for citizenship and land rights remaining elusive.

But, Kenya, a country where rogue officials routinely issue national IDs corruptly to ineligible aliens (with some blamed for carrying out terrorist attacks in the country), it is surprising how long it took for genuine cases such as the Makondes to be dealt with. It also remains to be seen how much longer other cases like the Nubi’s will be put to rest.

According to the UN’s refugee agency (UNHCR), about ten million people around the world are stateless. In West Africa, about a million people are either stateless or at risk of statelessness. Migration, defective citizenship laws, religious and/or ethnic discrimination are some reasons blamed for statelessness in many West African nations.

“Daily life for stateless people can be lonely and harrowing, and littered with obstacles,” the UNHCR said in Feb. 2015. “Having no ID documents means that you cannot register to go to school, open a bank account, buy property, access health services or legally marry.”