Pritzker Prize winning architect Francis Kéré on what the West still gets wrong about Africa

How does the world see Africa in 2022?

How does the world see Africa in 2022?

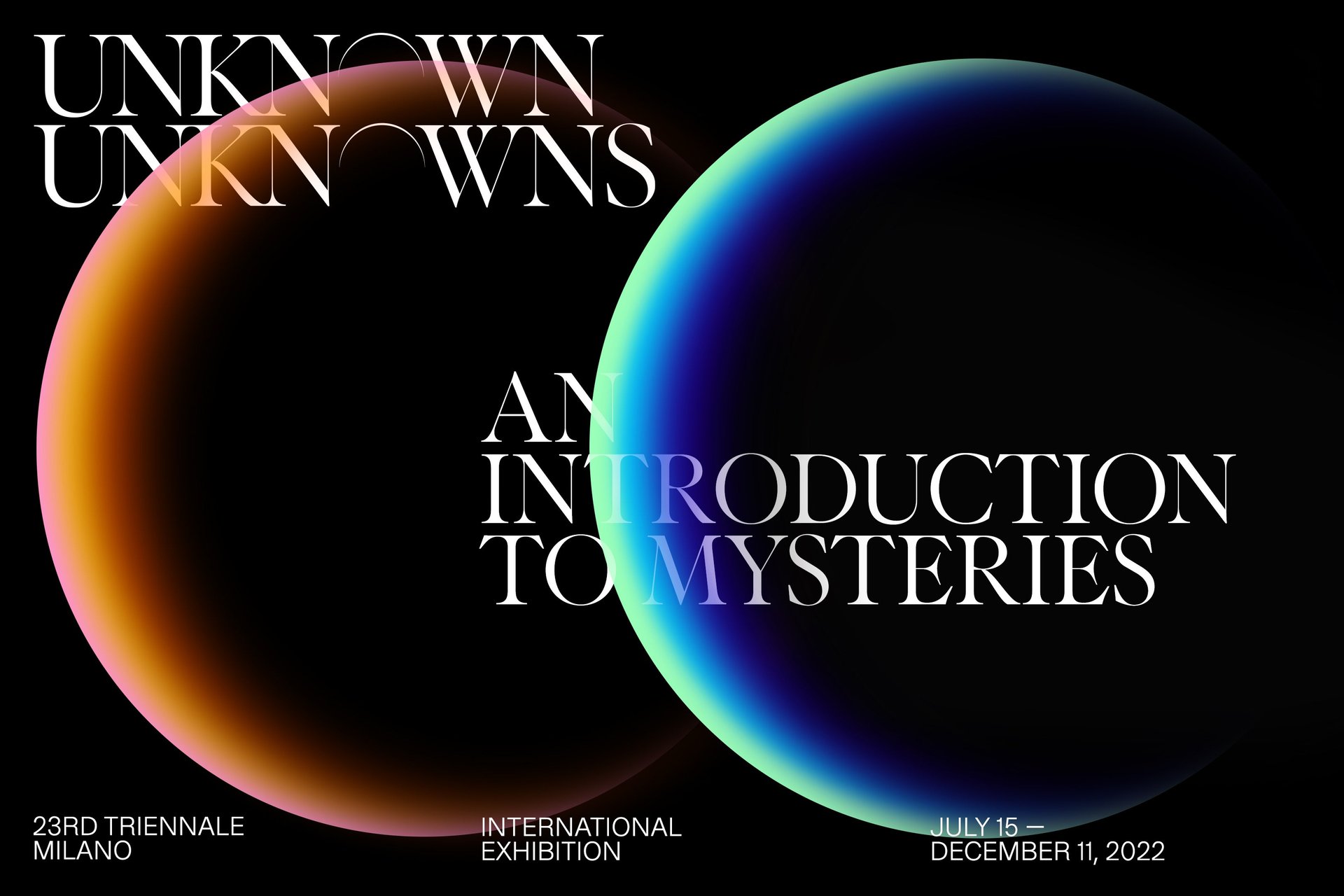

At the Triennale Milano’s new exhibition, the continent is curiously framed as an “unknown” alongside mysteries of the deep space and the origin of life.

Over the next five months, the century-old Italian cultural institution is showcasing the work of 400 artists, designers, and architects from 40 countries, in the hopes of becoming a kind of agora for creative thinkers around the world. “This plurality of points of view will allow us to expand our gaze to encompass what we do not yet know,” explained Stefano Boeri, Triennale Milano’s president. The African perspective is represented via national pavilions for Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Rwanda.

Representing a culture as a curiosity in an international exhibition is a tricky curatorial task. In the wrong hands, the show could deepen problematic expressions of Africanism—that queasy mix of “ignorance and appreciation” that’s akin to 19th century Orientalism, as sociologist Nataliya Nedzhvetskaya suggests. Or worse, an Africa-centric exhibit could recall the treatment of indigenous Filipinos and Congolese as “living exhibits” at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.

Thankfully, the task of navigating the assignment has largely been given to Francis Kéré, the astute Burkinabè architect who recently made history as the first African to win the Pritzker Architecture Prize which is considered as the field’s most prestigious accolade.

Kéré describes the job of representing Africa at the Triennale as both a privilege and a burden. Instead of publishing a heady manifesto, his tactic is to offer examples. Through a series of installations, Kéré shows off African ingenuity and slays some myths along the way.

At the international gallery, for instance, he erected a small building to showcase the graceful, sustainably-built architecture that’s become his trademark in Burkina Faso. Kéré also designed a seating area at the Triennale’s cafe that evokes community gatherings around a big shady tree practiced throughout Africa.

Kéré’s most ambitious installation is a 40-ft tower at the Triennale’s entrance. The immersive structure that invites visitors to kneel at one point, is meant to convey the exhibition’s theme of navigating the “Unknown, Unknowns” as well as showcase building techniques and materials extant in Africa.

We spoke to Kéré just before the exhibition’s July 15 opening. The following transcript has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Africa is framed as an “unknown” in this exhibition. What does the world not know about Africa at this juncture?

Francis Kéré: Africa is the closest neighbor to Europe but if you follow the discussions, it’s very clear that the West is is still not in a position to know what matters to young Africans. Instead of seeing it as a young, dynamic continent, Africa is still seen as a place that needs help. If you close your eyes to what matters to your neighbor, then you’ll never really know them.

There’s also still the tendency to talk about Africa as one country. Most are even unaware of the size of the continent. It’s so immense and culturally diverse; it’s a continent with its own values, history, and expectations on life.

How do you feel about being asked to be a kind of ambassador for an entire continent?

Kéré: Being able to talk about Africa is a privilege. I came from a very poor country and suddenly, through design, I have this kind of visibility. It’s wonderful but it’s also a little daunting. The best thing that I can do is to build on examples from Burkina Faso.

I want to highlight the idea that even through people are fighting to make a living, they’re generally happy and enjoy life. What makes Western people happy isn’t always what Africans want. Big cars might make an American happy but in Burkina Faso, a good mango tree or a beautifully-designed house out of wood or even cement blocks may be more meaningful.

Linking happiness and architecture is intriguing. Is this something you aspire for in your work?

Kéré: For me, creating something that helps people lead better, healthier lives is one of the main goals of architecture. I think about this no matter what project I’m working on.

If I’m designing a chair, for example, I think about how I can do it so people who sit on it feel supported and feel like stronger individuals, which I think will put them in the position of helping build a stronger community.

What makes African architecture worth knowing?

Kéré: Throughout Africa, groups of people have found a way to live in harmony with nature. If you look at the carbon footprint of this huge continent, it’s producing less than 5% of the world’s total emissions. Perhaps we can contribute [ideas] for the rest of the world.

The structure “Yesterday’s Tomorrow” is about the importance of the past. Already we’re talking about [3D]printing complete buildings, but if we build from knowledge and experience using the conventions we have, we have a chance to really serve humanity. If we don’t take this into consideration, we will fail.

Congratulations on winning the Pritzker Prize. Has it changed things for you?

Kéré: This [award] is the best thing that can happen to someone. It will for sure change my life completely and the life of my office.

The Pritzker is a big recognition, but I see it more as a push to go forward, you know. I’ve been awarded courage—I feel it, I see it. It’s like saying, “Go, Francis. Do it. Don’t fear.” I feel I have so much energy than ever before.

The heart is strong and the mind is ready to really keep going. [We want] to use these opportunities to expand our architecture from small to big and really try to care for humanity. Keep caring—that’s what we’re trying to do.

Caring is your calling. It even sounds like your last name.

Kéré: Yeah, it does! That’s my name!